Our analysis provides insights about patterns of giving

Austin’s top employment sectors are healthcare, education, business services, and government, but you wouldn’t know it based on local political giving.

According to The Austin Bulldog’s analysis of donations to City Council candidates in the first six months of 2020, the real estate and construction industries account for a significant share of political giving.

According to The Austin Bulldog’s analysis of donations to City Council candidates in the first six months of 2020, the real estate and construction industries account for a significant share of political giving.

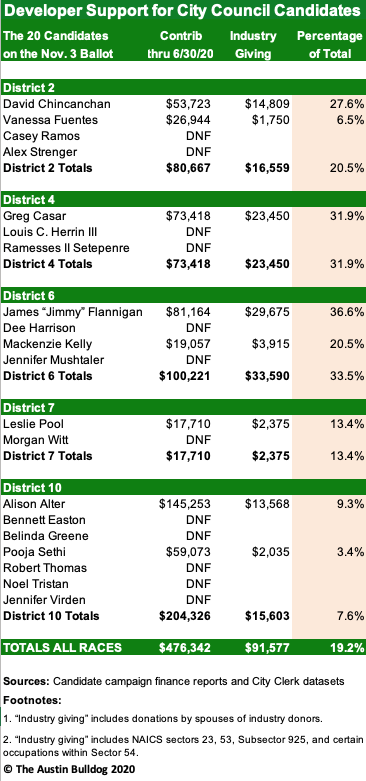

Overall, 19 percent of all candidate fundraising through June 30—some $91,500 out of $476,342—came from persons working in real estate, construction, or related professions like real estate law, architecture, brokerage, urban design, property management, or title insurance.

The bulk of that giving, nearly $68,000, went to just three candidates: District 4 incumbent Greg Casar, District 2 candidate David Chincanchan, and District 6 incumbent Jimmy Flannigan.

Employees at one large firm, Endeavor Real Estate Group, donated exclusively to those three candidates, for a total of $12,745. The firm describes itself as “one of the most active developers in Central Texas.”

These donations could help tip the scales in competitive races this year, as four council members seek reelection and four newcomers vie for an open council seat being vacated by District 2 incumbent Delia Garza. On July 14, 2020, Garza was elected to be the next Travis County Attorney.

Flannigan, who raised more than $81,000 through first half of the year, got about $30,000 of his total, or 37 percent, from developers and other stakeholders in the industry.

Casar’s share from the industry was about $23,500 out of $73,418, or 32 percent.

For Chincanchan, who until last November was chief of staff of District 3 Council Member Sabino “Pio” Renteria, the share was nearly $15,000 out of $53,723, or 28 percent. Chincanchan did not actually give up his position with Renteria but instead took a “leave of absence for political activity,” according to his personnel file obtained through a public information request.

Defining the developer nexus

For purposes of the analysis, we used a campaign finance dataset from the City Clerk and manually reviewed the “employer” and “occupation” entries for donations to 2020 council candidates, marking up which donations came from industry stakeholders.

The markup included donors who were employed in one of a handful of NAICS-defined industries: Sector 23 (“Construction”), Sector 53 (“Real Estate and Rental and Leasing Sector”), certain occupations within Sector 54 (“Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services”), including architectural services and real estate law, NAICS Subsector 624229 (“Other Community Housing Services”), and NAICS Subsector 925 (“Administration of Housing Programs, Urban Planning, and Community Development”).

People who indicated that they were investors in real estate or otherwise were involved in real estate-related financial services also were included.

The resulting list of donations from this broadly defined “developer nexus” reflected a diverse number of stakeholders—not a homogeneous group representing the same interests and supporting the same candidates.

Still, the analysis provided a tool for better understanding the scope of political engagement by persons involved in real estate, land use, and the ongoing building boom that Austin has experienced for many years.

‘It only makes sense…to desire a seat at the table’

To understand the outsized interest of the real estate sector in Austin politics this year, we turned to Emily Chenevert, CEO of the Austin Board of Realtors and treasurer of a political action committee going by the same name. What explains their involvement? What are they trying to achieve?

She replied through a public relations firm, saying, “From zoning cases to building regulations to sign ordinances and everywhere in between, local government plays a significant role in how the real estate industry operates and how stable our housing market is.”

“It only makes sense for those interested parties to participate in council races and to desire a seat at the table.”

Chenevert’s representative said that the Austin Board of Realtors PAC, which sat on a campaign chest of $262,131 as of June 30, “currently (is) in the midst of our candidate vetting process.” Candidates seeking funds from the PAC must answer a questionnaire and interview with a panel of realtor volunteers.

PAC support would be felt not through direct donations to candidates but through independent expenditures made to support the candidates they endorse or to attack their opponents. As previously reported by The Austin Bulldog, PACs spent more than $726,000 to influence the outcome of the 2014 mayor and council elections.

The candidates’ answers are evaluated against ABoR’s “Policy Principles,” which the representative said “prioritize private property rights, strategic land use, a stable housing market, and a thriving business community in Central Texas.”

Translation: the real estate group is invested in the outcome of a long-running debate over revising Austin’s Land Development Code (LDC), a process formerly known as CodeNEXT, now more blandly just called the “LDC Revision.” (ABoR has previously said that it was “deeply involved in the CodeNEXT process”).

Broadly speaking, the proposed rewrite would upzone parts of the city, allowing for denser development. That potentially would raise the property values for land owners—as well as property taxes—and increase profitability for the real estate business overall.

Given this context, we should expect that campaign donations from developers and other industry stakeholders would tend to flow to incumbents who support a rewrite of the land code, or newcomers perceived as being likely to support it.

And that’s exactly what we found in our analysis of campaign giving this year. The two incumbents who supported the changes—Casar and Flannigan—received about $51,000 from the industry, compared to about $10,000 that went to the two incumbents who opposed it, Leslie Pool and Alison Alter.

Setback for developers

The stakes in this year’s council races are high because the LDC rewrite already has floundered under two successive councils, despite enjoying majority support among the current council. The City’s long-running commitment to CodeNEXT is exemplified by the money spent to further its goals. Opticos Design Inc., the City’s consultant for CodeNEXT, through July 2019 was paid more than $7.8 million for its work on the code rewrite.

District Judge Jan Soifer struck down the latest land code revision in March. She ruled that the city improperly ignored a state law allowing property owners to challenge zoning changes that affect their properties or nearby properties.

The law says that a city is only allowed to ignore such protest rights by a supermajority vote of three-fourths of its governing body. In Austin, that would mean nine of 11 council members would need to pass the land code revision again to avoid a lengthy process of individual protest hearings. That’s significant because so far the council is split 7-4 on the land code revision.

Incumbents who opposed CodeNEXT

If the pro-development camp can widen its majority by two seats, then it will be able to pass a new land code along the lines of the one struck down by Judge Soifer.

That would mean defeating Leslie Pool in District 7, whose only opponent, Morgan Witt, is campaigning to “modernize the land use code.” But Witt did not appoint a campaign treasurer until July 1, 2020, and had raised no money through the latest reporting period. Pool had more than $24,000 in cash on hand as of June 30, 2020.

It would also mean defeating Alison Alter in District 10, who counts real estate broker Belinda Greene among her opponents, as well as attorney Pooja Sethi. Greene didn’t appoint a campaign treasurer until August 17, 2020, and won’t be required to report contributions until 30 days before the election, on October 5. Greene did not respond to a voicemail or email asking for comment on her policy positions.

Sethi, on the other hand, is sitting on a war chest of $55,199, of which $5,000 was a personal loan. Still, that’s less than half the $112,871 that Alter had in cash on hand June 30. Alter’s personal loan of $2,500 to her campaign is a debt carried over from her previous campaign. Only a small share of Sethi’s donations came from real estate interests, just 3.2 percent—the lowest share of any candidate who has so far reported raising money.

The District 10 campaign also drew four other candidates: Bennett Easton, Robert Thomas, Noel Tristan and Jennifer Virden. All four appointed treasurers after the June 30 report cutoff for reporting contributions.

Thomas ran for District 10 in the 2014 election that established geographic districts for council members. He loaned his campaign $100,000 that year and placed third in an eight-person field with 18.89 percent and 5,276 votes. He recovered $56,680 of his campaign loan and walked away with $43,320 in campaign debt.

Challenger in District 6

A supermajority also wouldn’t be possible without reelecting Jimmy Flannigan, who is being challenged by Mackenzie Kelly, a critic of the new land code. Flannigan had more than $60,000 in cash on hand through June 30, 2020, while Kelly had slightly more than $18,000.

Kelly got almost $4,000 from realtors and builders, less than a seventh of what Flannigan raised from the industry, but it accounted for more than 20 percent of her fundraising.

Kelly ran for the District 6 seat in 2014, placing fifth in a six-person field with 8.98 percent and 1,382 votes. Flannigan also ran in 2014. He got into a runoff with Don Zimmerman and lost, then came back to beat Zimmerman in 2016 with 55.94 percent and 15,440 votes.

The District 6 slot drew two other candidates as well, Dee Harrison and Jennifer Mushtaler. Both appointed treasurers in August and had raised no money.

Open seat in District 2

To achieve a supermajority, the pro-development camp also would have to hold on to the seat being vacated by Delia Garza, a major supporter of the land code revision.

The developers’ favorite in the race appears to be David Chincanchan, whose former boss Renteria voted for the new LDC.

Chincanchan’s opponent Vanessa Fuentes got 6.5 percent of her campaign contributions from persons employed in real estate or related fields (compared to Chincanchan’s share of 27.6 percent) and most of that was small gifts from independent realtors or attorneys—not large donations from big firms.

Fuentes and Chincanchan voiced different views on the land code during an August 20 virtual event moderated by Paul Saldaña, co-founder of the Hispanic Advocates Business Leaders of Austin (HABLA).

Fuentes said, “When we’re looking at the Land Development Code update, what I like to ask myself is: Who are we growing for? Who benefits from these changes, and more importantly, who gets left behind?”

She proposed “a fully funded anti-displacement program and more anti-gentrification measures adopted into the Land Development Code update.”

Chincanchan said, “Our current Land Development Code hasn’t changed significantly since the 1980s, and it is rooted in a segregationist racist plan from 1928.”

“In our community over the last several years…we have seen the effect of gentrification, we have seen displacement, we have seen real suffering. All of those things that we want to address are happening under the current Land Development Code. So we should be clamoring for change.”

Lobbyist donations

Section 2-2-53 of the Austin City Charter states that no person who is compensated to lobby the city council and who is required to register with the City as a lobbyist, and no spouse of that person, may contribute more than $25 in a campaign period to an officeholder or candidate for mayor or city council, or to a specific purpose PAC involved in the election for mayor or city council.

The $25 limitation on lobbyist contributions does not apply to others employed in the same company as the lobbyist. Our analysis shows that attorneys employed by law firms that lobby the city council on behalf of developer clients donated heavily.

The foremost example of that practice is Armbrust & Brown PLLC, the biggest Austin-based firm in terms of political giving by its employees. The firm bills itself as having “particular expertise in complex real estate transactions, construction, and development,” according to its website.

Its clients include property owners, developers, investor groups, property managers, and financial institutions with real estate interests.

Eighteen of Armbrust’s 29 attorneys gave to one or more local candidate so far this year, for a total of $22,725. Nearly all of these lawyers gave $400, the maximum allowed under the City Charter, with married employees’ spouses generally also giving $400 each.

Whellan

Founding partner David Armbrust and two fellow attorneys—Michael Whellan and Richard Suttle—were the only ones who limited themselves to the $25 maximum that registered lobbyists are allowed to donate under the City Code.

In other words, senior partners at the firm registered as lobbyists and complied with the resultant $25 limit, while more junior attorneys and their spouses donated to the max. David Armbrust did not respond to a request for comment.

The pattern of giving at Armbrust & Brown was uniform and unmistakable: all but one donation from employees—52 of 53 total donations—went to just three council candidates: Greg Casar, Jimmy Flannigan, and David Chincanchan.

What’s a lobbyist?

The giving culture at Armbrust & Brown is sharply different from that of other law firms in the area, whose employees did not uniformly give to certain candidates.

For example, only five employees of Husch Blackwell LLP, a firm with 64 Austin attorneys, according to data compiled by the Austin Business Journal that’s available only to subscribers, gave to local candidates, and each of them gave $25.

Attorney Stephen Drenner of the Drenner Group, along with three colleagues and the spouse of a colleague, each gave $25 to five different council candidates.

In all, Drenner Group contributions totaled just $300—compared to $22,725 donated by Armbrust & Brown attorneys. The Drenner Group employees who donated all are registered as lobbyists focusing on land issues.

These different giving practices raise a question: How do law firms make the decision to register certain attorneys or staff as lobbyists, but not others?

Some firms take a conservative approach, erring on the side of over-disclosure. One attorney at Husch Blackwell, Micah King, told the Bulldog that he was registered to represent an engineering firm even though he had “never heard of it.”

An assistant had filed the disclosure form, he explained, and “thought that I had done some lobbying for that engineering firm.”

In case he was pulled into work for that client, it was better to “err on the side of inclusion to ensure compliance and transparency,” the attorney noted.

The Drenner Group’s founding principal, Stephen Drenner, did not respond to a request to comment on how his firm makes the decision to register certain attorneys or staff as lobbyists.

Drenner Group identifies itself as a “a real estate boutique law firm that specializes in land use, entitlement issues and incentive requests.”

Chapter 4-8 of the Austin City Code defines lobbyist to mean a person who communicates directly with a city official “to influence or persuade the City official to…take action or refrain from taking action on a municipal question.”

It defines “municipal question” to include possible actions pending before the council, but not “routine, non-appealable decisions on permitting, platting, and design approval matters in connection with a specific project or development.”

So a lawyer lobbying the council generally in support of a new land code would be required to register as a lobbyist, and would be limited to a $25 donation, but a lawyer lobbying for a single zoning change wouldn’t have to register.

Project Connect

Besides the Land Development Code, another key issue will be on the ballot this November. Project Connect is a mass transit plan intended to ease Austin’s traffic snarls. Critics say it imposes an additional property tax burden that residents can’t afford.

Some developers and industry groups plan to back the measure through political action committees. For example, the Austin Board of Realtors PAC gave $25,000 through the Austin Community Foundation to support Transit for Austin, according to a July 15 campaign finance report.

Asked for more details about this, ABoR told the Bulldog, “These funds were dedicated to Transit for Austin as a commitment to exploring how a mass transit investment could benefit our community ahead of the specific design of Project Connect.”

Not all real estate dollars are going to the same causes. Our Mobility Our Future, a PAC opposing Project Connect, raised $24,000 from John Lewis, a real estate investor.

The bulk of donations in support of the transit plan probably haven’t been made, because the council didn’t vote to put the measure on the ballot until August 13—six weeks after the June 30 cutoff for campaign finance disclosures.

If approved by voters, Project Connect could boost development along the new light rail corridors, including what some developers call “transit-oriented development.” For example, New York-based real estate investment firm MSquared recently revealed it was scouting spots in Austin for a seven to nine story mixed use project containing 100-200 apartments.

Alicia Glen, MSquared’s managing principal, told culturemap Austin that the firm would look at sites along transit corridors if voters approved Project Connect.

The Austin Chamber of Commerce and the Real Estate Council of Austin published a joint resolution in support of Project Connect August 26, calling for “additional housing and density along the Transit Priority Network corridors…including an emphasis on transit-oriented development, transit-oriented communities, and transit-based zoning.”

This story was updated at 1:17pm August 28, 2020, to include District 10 candidate Jennifer Virden, who was in inadvertently omitted.

Trust indicators: Bulldog reporter Daniel Van Oudenaren is a journalist with more than 10 years experience in local, state, and international reporting.

Trust indicators: Bulldog reporter Daniel Van Oudenaren is a journalist with more than 10 years experience in local, state, and international reporting.