Justice

No Gun, No Self-Defense

Legal Battle Won But War Ahead

Legal Battle Won But War Ahead

Victim got a copy of record sought, but a second

lawsuit looms over new public information request

by Ken Martin

© The Austin Bulldog 2017

Part 9 in a Series

Posted Monday August 7, 2017 11:39pm

Updated Tuesday August 8, 2017 9:51am (to link to Settlement Agreement)

> The public information request that gave rise to a lawsuit in which Travis County Attorney David Escamilla sued Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has been withdrawn. And with it the litigation over whether the County Attorney must provide the document at issue, as ordered in the AG’s open records ruling.

The public information request that gave rise to a lawsuit in which Travis County Attorney David Escamilla sued Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has been withdrawn. And with it the litigation over whether the County Attorney must provide the document at issue, as ordered in the AG’s open records ruling.

>The matter was put to rest when a Settlement Agreement was reached today that allowed the requestor to have an unredacted copy of the Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) the County Attorney entered into with her abuser.

Escamilla declined to comment until a copy of the Settlement Agreement is filed. The Austin Bulldog filed a public information request for a copy of the Agreement and it was not immediately received. (It will be linked at the bottom of this story when obtained.)“We settled,” Austin attorney Bill Aleshire of Aleshire Law PC, told The Austin Bulldog in a telephone interview late yesterday.

Escamilla declined to comment until a copy of the Settlement Agreement is filed. The Austin Bulldog filed a public information request for a copy of the Agreement and it was not immediately received. (It will be linked at the bottom of this story when obtained.)“We settled,” Austin attorney Bill Aleshire of Aleshire Law PC, told The Austin Bulldog in a telephone interview late yesterday.

The agreement requires the requestor not to publish or assist anyone in publishing the DPA. “But she may give it to her attorneys, counselor, or therapist. And it can be entered into any official court proceeding,” he said.

> The ability to enter a copy of the DPA into court proceeding is important because the requestor, Tara Coronado, is in a custody dispute with her abuser and former husband over whether one of her four children will be sent to an out-of-state boarding school.

The ability to enter a copy of the DPA into court proceeding is important because the requestor, Tara Coronado, is in a custody dispute with her abuser and former husband over whether one of her four children will be sent to an out-of-state boarding school.

>At the request of her attorney in that dispute, Coronado declined to personally comment on the Settlement Agreement.

One battle won, a war ahead

Must Deferred Prosecution Agreements be Secret?

Must Deferred Prosecution Deals be Secret?

County attorney denies victim of domestic

violence right to see deal her abuser got

by Ken Martin

© The Austin Bulldog 2017

Part 8 in a Series

Posted Wednesday July 5, 2017 1:59pm

Updated Wednesday July 5, 2017 2:55pm to add Coronado's statement about putting DPA online

Updated Wednesday July 5, 2017 3:40pm to strike incorrect sentence re: couldn't rely on previous determination

Updated Thursday July 6, 2017 10:08am to provide the correct blank form the county attorney uses for DPAs

The next stage in a legal battle over a prosecutor’s discretion to withhold certain records played out last Thursday in a state district court.

The Travis County Attorney’s Office and an intervenor in the county attorney’s lawsuit against the Texas Attorney General argued over which parts of the Texas Public Information Act (TPIA) would govern arguments when the matter goes to trial August 8.

“It’s prudent to give you a clear ruling on what’s going to trial,” Judge Lora Livingston of the 261st District Court told the attorneys at the conclusion of the hearing, after listening to nearly two hours of arguments.

“It’s prudent to give you a clear ruling on what’s going to trial,” Judge Lora Livingston of the 261st District Court told the attorneys at the conclusion of the hearing, after listening to nearly two hours of arguments.

On Friday, Livingston ruled that plaintiff Travis County Attorney must limit arguments in favor of withholding a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) to the same grounds the county stated when it asked the Attorney General for a ruling.

A DPA is an agreement signed by the prosecutor, the defendant and the defendant’s attorney. It sets forth conditions that if met will result in dismissal of criminal charges. (More details about DPAs later.)

In its request for a ruling from the Attorney General (AG), the county cited only what’s commonly called the “law enforcement exception” contained in Section 552.108(a)(1):

“Information held by a law enforcement agency or prosecutor that deals with the detection, investigation, or prosecution of crime is excepted from (release) if: release of the information would interfere with the detection, investigation, or prosecution of crime.”

At Thursday’s hearing, Assistant County Attorney Tim Labadie argued that the county had not cited other sections of the Act because previous determinations by the AG had allowed the very same DPA to be withheld.

At Thursday’s hearing, Assistant County Attorney Tim Labadie argued that the county had not cited other sections of the Act because previous determinations by the AG had allowed the very same DPA to be withheld.

He asked the judge for permission to claim several other exceptions set forth under Sections 552.108(a)(2), 552.103, and 552.107.

The judge denied his request.

Attorney Bill Aleshire of Aleshire Law PC won the ruling by citing Section 552.326 which states, “the only exceptions to required disclosure … that a governmental body may raise in a suit filed under this chapter are exceptions that the governmental body properly raised before the attorney general in connection with a request for a decision regarding the matter….”

Attorney Bill Aleshire of Aleshire Law PC won the ruling by citing Section 552.326 which states, “the only exceptions to required disclosure … that a governmental body may raise in a suit filed under this chapter are exceptions that the governmental body properly raised before the attorney general in connection with a request for a decision regarding the matter….”

Why county sued the AG

County Attorney Escamilla Wants to Close the Courtroom, Seal Records

County Attorney Escamilla Wants to

Close the Courtroom, Seal Records

‘The Austin Bulldog’ intervenes to oppose

this unusual action to deny public access

by Ken Martin

© The Austin Bulldog 2017

Part 7 in a Series

Posted Friday February 25, 2017 12:21am

Updated Tuesday February 28, 2017 5:02pm to clarify Escamilla's statements (see underlined text)

To keep a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) from being obtained by a victim of domestic violence — and ensure that it isn’t widely disseminated — Travis County Attorney David Escamilla has taken the extraordinary step of requesting that a hearing be held in a closed courtroom and that the related exhibits, motions, and responses to be argued in court be sealed because they might make reference to the DPA.

To keep a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) from being obtained by a victim of domestic violence — and ensure that it isn’t widely disseminated — Travis County Attorney David Escamilla has taken the extraordinary step of requesting that a hearing be held in a closed courtroom and that the related exhibits, motions, and responses to be argued in court be sealed because they might make reference to the DPA.

The Austin Bulldog filed a petition February 21, 2016, to intervene and oppose the County Attorney’s petition.

Courts are rarely closed, except in some family law cases involving child custody. Honoring this principle provides transparency and accountability. It avoids courts being thought of pejoratively as a Star Chamber, the ancient English tribunal “established to ensure the fair enforcement of laws against socially and politically prominent people so powerful that ordinary courts would likely hesitate to convict them of their crimes.”

If the County Attorney’s petition is granted it would deny public access to courts, which is a cornerstone of our system of justice that is grounded in Texas law and the First Amendment, although this right is not absolute. Courts are sometimes closed to prevent dissemination of sensitive information to the public, such as matters dealing with attorney-client privilege, trade secrets, and matters of national security.

The Austin Bulldog’s motion states that the County Attorney’s petition to seal records fails to articulate — or to provide any evidence at all — of any “specific, serious and substantial interest which clearly outweighs” the presumption of openness of court records.

Attorney Bill Aleshire represents the Bulldog in this matter, citing in the motion Texas Rules of Civil Procedure 76a(3), which allows non-parties who pay a filing fee to intervene as a matter of right for the limited purpose or participating in proceedings.

Attorney Bill Aleshire represents the Bulldog in this matter, citing in the motion Texas Rules of Civil Procedure 76a(3), which allows non-parties who pay a filing fee to intervene as a matter of right for the limited purpose or participating in proceedings.

“Trust in any governmental activity is enhanced with transparency,” said Aleshire, a former Travis County judge and before that tax assessor-collector. “And that trust is diminished with secrecy. Why should any deals a prosecutor makes with any defendant be concealed from the public? Is secrecy about prosecutor deals really in the public interest? In this day of enhanced concerns about equal justice (e.g., Black Lives Matter) does secrecy about who gets what deal from a prosecutor enhance or diminish trust and respect for the criminal justice system?”

A hearing on the matter was originally scheduled for February 22. The hearing was rescheduled for March 8 after the County Attorney learned through The Austin Bulldog’s motion and Aleshire’s e-mails to him that the county had failed to comply with the requirement to post notice with the Clerk of the Supreme Court of Texas.

Why intervene?

Boards of Examiners Ripped for Backlogs

Boards of Examiners Ripped for Backlogs

Sunset Review rough for boards that license and regulate

professionals who play key roles in child-custody cases

by Ken Martin

© The Austin Bulldog 2016

Part 6 in a Series

Posted Friday December 16, 2016 10:39am

The Austin Bulldog’s investigation of problems in family law courts involving child-custody cases includes a review of complaints against some of the professionals appointed by courts to provide related services. Specific complaints will be detailed in later installments of this ongoing series. An overarching question is why does it take two or three years to resolve complaints against these practitioners? The answer was revealed in the biennial exercise known as Sunset in Texas, which is now underway.

Sunset in Texas is not the romantic experience the name might imply. It’s not a time for kicking back, sipping a beer, and watching the sun dip into the chilly waters of Lake Travis. Sunset in Texas is a time for a deep and probing examination of a good portion of the 130-odd Texas governmental agencies to learn how well they are performing. It’s a time for determining whether the sun should set on their work and deciding if these agencies should fade into history.

Although the Sunset process for the 2016-2017 cycle is scrutinizing 25 separate agencies, this story will focus solely on the four professions whose services are utilized to varying degrees in family law cases involving child custody: Professional Counselors, Psychologists, Social Workers, and Marriage and Family Therapists.

Practitioners in each of these professions are licensed and regulated by a separate Texas State Boards of Examiners. Each of these boards will be abolished unless lawmakers reauthorize them in the 85th Session of the Texas Legislature that convenes January 20.

As with all agencies now under review, if these four are reauthorized they could be radically reformed. They could also be moved under the umbrella of a different state agency.

Three of these Boards of Examiners—for Professional Counselors, Social Workers, and Marriage and Family Therapists, which collectively oversee some 50,000 licensees—currently receive administrative support from the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS).

It’s apparent these three boards will not be left to continue floundering as they have been, based on the scathing review of their performance aired during a December 8 hearing of the Sunset Advisory Commission. Under the current operating procedures and with insufficient staff support from DSHS, they have not kept up with the workload. The backlog of unresolved complaints against the professionals they regulate has grown exponentially in recent years.

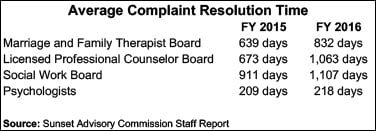

During Fiscal Years 2000 through 2006, the average length of time for these three boards to resolve complaints rarely exceeded 200 days. But since FY 2007 the length of time needed to resolve complaints has been rising steadily and now stands at 2.3 years for marriage and family therapists, 2.9 years for professional counselors, and 3 years for social workers.

During Fiscal Years 2000 through 2006, the average length of time for these three boards to resolve complaints rarely exceeded 200 days. But since FY 2007 the length of time needed to resolve complaints has been rising steadily and now stands at 2.3 years for marriage and family therapists, 2.9 years for professional counselors, and 3 years for social workers.

These delays fail to protect the health and safety of Texans—many of whom are struggling with litigation and mental stress. The delays also soil the reputation of practitioners who may have been wrongfully accused of misconduct and would like a timely opportunity to clear their names.

The Sunset Advisory Commission Staff Report recommended that the Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors, Social Workers, and Marriage and Family Therapists all be transferred to the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation (TDLR) by August 31, 2018.

In addition the staff report recommended that the boards’ complaints and ethics committees be abolished, that board members not be involved in investigating complaints, and that TDLR develops a policy for prioritizing complaints and updates enforcement plans. In addition the report calls for throwing a wider net when checking the backgrounds for licensure applicants to include fingerprints and checks for disciplinary actions taken in other states.

Psychologist examiners board excels

A Troubled Father’s Last Chance

Custody Dispute Ends in Mistrial

Commissioners Respond to ‘Extortion’ Complaints

Commissioners Respond to ‘Extortion’ Complaints

But discuss only cost of Williamson County Domestic

Relations Office, and claim need for judges to buy in

by Ken Martin

© The Austin Bulldog 2016

Part 3 in a Series

Posted Tuesday April 26, 2016 4:03pm

After months of hearing from parents who claim they are being ripped off by racketeering in the family courts of Williamson County, Precinct 1 Commissioner Lisa Birkman briefed the Commissioners Court about research she had done to explore the possibility of establishing a Domestic Relations Office (DRO). That is a goal advocated by the Texas Association for Children and Families (TACF).

After months of hearing from parents who claim they are being ripped off by racketeering in the family courts of Williamson County, Precinct 1 Commissioner Lisa Birkman briefed the Commissioners Court about research she had done to explore the possibility of establishing a Domestic Relations Office (DRO). That is a goal advocated by the Texas Association for Children and Families (TACF).

Birkman described the duties of the professionals who are appointed by courts to assist in making decisions about child custody. The person appointed will interview the children, parents, and others and report to the judge, she said. In Williamson and most other Texas counties the person appointed would be an attorney or other licensed professional in private practice.

She noted that the Family Code allows the Commissioners Court to establish a DRO, such as the one operated by Travis County. Among other services provided by the Travis County DRO, it has employees qualified to be appointed as guardian ad litem to advise the court on the best interests of children.

“There's only a few counties that do it that way and it's expensive,” Birkman said. (Actually there are eight such counties in Texas, per the Texas Association of Domestic Relations Offices.)

Birkman cited cost figures for three DROs:

• Harris County (Houston) has 42 employees and a $3.3 million annual budget.

• Tarrant County (Fort Worth) has 83 employees and a $7.2 million budget.

• Travis County (Austin) has 51 employees and a $3.6 million budget.

“The way we do it in Williamson County, and most counties in Texas, is the parents bear the cost,” Birkman said.

Judges not yet responsive