About 9,800 words

This package of four articles was originally published in The Good Life magazine in August 2001. The result was, by far, the largest and most impassioned response garnered from the many hundreds of feature articles published during more than eleven years the magazine lasted (October 1997 through January 2009). Which is a strong indication of just how much people love animals.

Photography by Barton Wilder Custom Images

It’s mid-morning on Friday, July 13, at Austin’s Town Lake Animal Center and the facility is humming with activity. Dr. Kathy Jones, head veterinarian, is spaying and castrating adoptable dogs with practiced ease while the radio plays soothing classical music. On the operating table a sedated young male dog is splayed on its back, legs restrained. Jones deftly slices the skin, squeezes the scrotum till the tiny testicles squirt out, then snips them off, ties off the blood supply and spermatic cord, and seals the wound. A veterinary technician tattoos the dog’s belly to signify no more male.

Next up is a small female dog, which takes far longer to operate on. A long incision in the midsection, a parting of the flesh, the ovaries and uterus are fished out, snipped, the remaining parts are tied and sewn up. The exterior skin is glued and she’s tattooed to signify no more female. She is wrapped in a towel and toted into the next room.

Soon these newly altered pets will be in a cozy heated cage to stay warm until recovered and ready for the regular pens. Slice, snip, sew and tattoo is a routine that will go on for two or three hours on the average day, when some fifteen animals will go under the knife, sometimes with Jones operating alone, sometimes in a tag-team operation with the other full-time vet on staff. It’s a routine procedure, executed with precision. Voilà! In the flash of a scalpel another adoptable animal has been made ready to go home with some happy family to play but not propagate, one more brick in the wall that’s meant to slow down what goes on in an adjacent room.

A year-old female cocker spaniel mix lies on a stainless steel gurney. Much of her brown hair is missing due to a severe skin disease. Her nails are long and unkempt, indicating she hasn’t been walked or groomed. Shaggy with ticks, she was picked up by an animal control officer July 9 as a stray wearing a collar but no tags. She was snared about a block from Govalle Elementary School in East Austin. Nobody came to claim her. Her three days of grace are up. Her time has come. She is scanned to make sure that no one has overlooked an implanted microchip that would help find the owner. There is none. “This guy’s in pretty bad shape,” says Amber Rowland, community awareness coordinator for Town Lake Animal Shelter (TLAC). “She’s pretty friendly, actually, but she’s not healthy enough to qualify for adoption.”

A woman veterinary technician strokes her scraggly brown fur and leans over to cradle and hold the dog on the gurney, while a male technician finds the cephalic vein on the dog’s right forepaw. She makes not a whimper as the needle slides into the flesh. As the syringe pushes sodium pentobarbital into her body (the brand name is Fatal Plus; technicians call it “blue juice”) the dog’s head instantly falls limp and the light dies in her eyes. A “heart stick” is plunged into the side of her chest, piercing the heart. The stick throbs for a while as the heart ticks out its few last beats. When the stick stops pulsating, the technicians check to make sure there is no respiration, then slide the body into a plastic bag, close it, and carry it a few paces to the freezer, where it will stay until the truck comes to carry the body, along with scores of others, to Waste Management’s landfill, the mass burial ground for abandoned and stray animals that can’t be salvaged.

A woman veterinary technician strokes her scraggly brown fur and leans over to cradle and hold the dog on the gurney, while a male technician finds the cephalic vein on the dog’s right forepaw. She makes not a whimper as the needle slides into the flesh. As the syringe pushes sodium pentobarbital into her body (the brand name is Fatal Plus; technicians call it “blue juice”) the dog’s head instantly falls limp and the light dies in her eyes. A “heart stick” is plunged into the side of her chest, piercing the heart. The stick throbs for a while as the heart ticks out its few last beats. When the stick stops pulsating, the technicians check to make sure there is no respiration, then slide the body into a plastic bag, close it, and carry it a few paces to the freezer, where it will stay until the truck comes to carry the body, along with scores of others, to Waste Management’s landfill, the mass burial ground for abandoned and stray animals that can’t be salvaged.

While the cocker spaniel is being dispatched, a six-month-old black Labrador retriever crawls into the narrow space between a cabinet and the wall, not out of any knowledge of his fate, but so shy and fearful that he would never be seen by potential adopters as a candidate for fetching a Frisbee. As the technician gently pulls him into the open, the dog’s tail is tucked between his legs. Compounding his lack of appeal is a golfball-sized abscess under his left eye, which the Center had already drained, irrigated and treated with an antibiotic. In time, the abscess would heal, but this stray, brought to the Center July 8 by a citizen, will not live that long. “He’s most likely here (to be killed) because he has the abscess and because he is somewhat fearful; he’s not an ideal candidate (for adoption), so we have to do it,” Rowland says. “We try to do it as well as we can when we have to.” The attendants are indeed gentle, loving and kind. They do their distasteful duty professionally and soon his lifeless body is bagged and added to the silent freezer.

“We play with them one last time before we send them to god,” Dorinda Pulliam, director of Town Lake Animal Shelter since last October, says of the procedure used to kill animals. “Prior management would never go near the place and would try to run it without dealing with what’s happening in that room.”

Despite the efforts of the Center’s staff and scores of rescue groups, this killing will go on for the foreseeable future-nevermind the fact that both the Austin City Council and the Travis County Commissioners Court adopted No-Kill Millennium resolutions in December 1997-because supply far exceeds demand.

About 150,000 animals have been killed at TLAC since late 1992, which is when the City of Austin took over the operation. The first year of city control was the year of the big slaughter, when more than 23,000 animals were killed, an average of ninety per weekday for the entire year. Things have improved over time but for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2000, the average death toll was still about fifty animals per weekday. Since October 1, the average has dipped to forty-four.

Stray animals arriving at TLAC that are registered with the city are given a ten-day reprieve. Animals with other forms of identification are kept at least five days. Unregistered animals without identification have but three working days before they may be put up for adoption, placed with a rescue group, or killed, Dorinda Pulliam says.

Stray animals arriving at TLAC that are registered with the city are given a ten-day reprieve. Animals with other forms of identification are kept at least five days. Unregistered animals without identification have but three working days before they may be put up for adoption, placed with a rescue group, or killed, Dorinda Pulliam says.

Rowland says the fate of an animal given up by its owner can be decided immediately. This is no small problem. A gut-wrenching twenty-two percent of the animals taken in by TLAC from October 1, 2000, through June 30, 2001—a total of 3,679 animals-were surrendered by owners. This fact is especially deplored by people active in animal rescue groups.

Patricia “Pat” Valls-Trelles has been a member of the City Council-appointed Animal Advisory Commission since it was created in 1992. People in the rescue community call her the “TLAC cop,” although she prefers “watchdog.” She visits TLAC daily and calls its receiving section “the most depressing place in the shelter.” “When they pick up strays, there’s always the hope they will be reclaimed. When someone brings in their companion they no longer want, I think that’s very sad.”

Kathy Pardue of Austin Feral Cats says of receiving, “I can stand it for about thirty minutes and I’m in tears. People drop off their animals for idiotic reasons, like, ‘My new boy friend doesn’t like cats,’ or ‘We’re moving and our new place doesn’t allow us to take our ten-year-old cocker spaniel, and we didn’t look for another place that would let us.'”

Kathy Pardue of Austin Feral Cats says of receiving, “I can stand it for about thirty minutes and I’m in tears. People drop off their animals for idiotic reasons, like, ‘My new boy friend doesn’t like cats,’ or ‘We’re moving and our new place doesn’t allow us to take our ten-year-old cocker spaniel, and we didn’t look for another place that would let us.'”

Amber Rowland says a big problem with people giving up animals to the shelter is they never should have gotten that particular breed to begin with. “People get frustrated with traits they’re not aware off,” she says. For example, Bassett Hounds are not easily trained for a leash because they are bred to be independent thinkers.

“People think all small dogs are lap dogs,” says Kim Barry, a PhD animal behaviorist on the TLAC staff. She tells a story about a colleague who works in New York who fielded a complaint from a man whose Rat Terrier had eaten through a wall. The response? “You’ve got a great Rat Terrier! He’s going after rats.”

Jack Russell Terriers are one of many other problematic breeds. Depicted as little angels in television and film roles, they are anything but. One web site for this breed has about three pages of traits that should sober up anyone fooled by the breed’s tiny size and film portrayals.

Rowland advises prospective animal owners to consult reputable publications, such as the ASPCA’s Complete Guide to Dogs: Everything You Need to Know About Choosing and Caring For Your Pet.

Austin Pets Alive, the organization most responsible for passage of a No-Kill Millennium resolution, is trying to change the way people think about animals, advocating the phrase “animal guardian” instead of “animal owner.”

“Legally, animals are the same as a bicycle or a chair,” Kathy Pardue says. “They’re just property. Ethically, people who care about animals don’t see them in that manner.”

Until a new millennium of universal understanding, however, animals are nothing more than property to many owners and, as with any other kind of property, some people take good care of their possessions, some don’t. When animals are not taken care of, they become the responsibility of TLAC. Animal control officers, who by law are required to pick up dogs that not restrained from running at large, bring in sixty-nine percent of the dogs, cats, and other animals that arrive at the facility. (See accompanying story, below, “Fleet Footed Canine Catchers.”)

TLAC had been operated since 1954 by the Humane Society of Austin and Travis County, under a contract that leased the city’s land for a dollar a year. According to stories published at the time in the Austin American-Statesman, an audit in late 1992 revealed, “Wrong animals were being euthanized, feeding regimens were improper and sanitation was abysmal” at the facility that could house about five hundred animals. (Karen Medicus, the current executive director of the Humane Society/SPCA of Austin and Travis County, says it was not an audit, per se, but an evaluation report done by a team from the American Humane Association.) In January 1994, the Austin City Council voted unanimously to pay the Humane Society $1.6 million for the replacement cost of the buildings it owned at the site. The Humane Society opened a new facility at 124 W. Anderson Lane and renovated it in 1994. (See “Humane Society Does It Right.”)

As deplorable as it is to have to kill thousands upon thousands of animals every year at TLAC, over the last five years the number of animals killed has been steadily declining, as has the number of animals taken into the facility each year. Also encouraging is that the number of adoptions has steadily increased each year. For the year ending September 30, 1995, more than ten times as many animals were killed as were adopted. For the year ending September 30, 2000, fewer than four animals were killed for each one adopted.

Rescue groups play a huge role and are saving far more animals than TLAC is able to place in direct adoptions. From October 1, 2000, through June 30, 2001, rescue groups took 3,085 animals out of the facility, while 2,453 animals were adopted.

How to make more progress toward achieving the No-Kill Millennium is a problem that has both TLAC officials and rescue groups vexed. While they are still talking and not barking at each other, relations are not altogether cozy.

But let’s clear up something right now: the No-Kill moniker is a complete misnomer. The name implies that no animals will be put to death when the goals are achieved. Nothing could be further from the truth. The actual goal is to stop killing animals that are adoptable.

An adoptable animal is a healthy animal that has passed a temperament test for sociability and is deemed ready to become a lifetime companion. The protocol that Barry developed for TLAC’s test is still being field-tested and may be revised. Upon testing, animals are classified in one of three categories: (A) adoptable, (T) treatable, or (N) nonrehabilitatable. The latter category, Barry says, applies to an animal that displays overt aggression. “It’s pretty hard to get an N rating,” says Amber Rowland, although feral cats are usually considered poor candidates for adoption. “Animals can revert quickly to being unrecoverable, socially,” she says. Barry adds, “TLAC is not set up in any way to be a rehabilitation shelter.”

The overarching problem for TLAC and for animal advocacy groups is that there are too many animals not being taken care of properly in the larger community. Exactly how many animals there are hereabouts, nobody actually knows. It’s not something the U.S. Census Bureau tallies. There are some clues, however. The American Veterinary Medical Association has established formulas to estimate the number of pets, based on the number of households-which is something the census does count. The City of Austin, according to the city’s chief demographer, Ryan Robinson, had 265,649 households identified in the 2000 census. Running the formulas yields an estimate of about 142,000 dogs and 159,000 cats. But these are pets, animals that people own. These numbers do not include stray, feral, or “loosely owned” animals, the latter being pets that neighborhood residents may feed but nobody claims. According to a survey in Santa Clara County, California, published by the National Pet Alliance, forty-one percent of the cat population was unowned. Assuming similar results in Austin, increasing the cat population by forty-one percent would bring the total number of cats to about 224,000.

For Travis County (including Austin), which has 320,766 households, the formulas yield a dog population of about 171,000 and a cat population of 192,000. Applying the forty-one percent for unowned cats would boost the number of felines to more than 270,000.

While these numbers are somewhat speculative, they give a sense of what the TLAC and rescue groups are up against in trying to reduce the number of animals being killed. There are hundreds of thousands of animals in our abodes and on our streets.

Through the first nine months of the fiscal year that started October 1, 2000, TLAC killed 8,558 animals, or forty-nine percent of the 17,382 animals that left the shelter during that period. TLAC Director Dorinda Pulliam says, “The No-Kill resolution says we’ll save every adoptable animal, not every animal. We save fifty percent of the animals that come into the shelter. We euthanized forty percent of adoptable animals last month. If we were saving the right fifty percent, we would already be achieving the No-Kill Millennium, as it’s stated.

“The rescue groups don’t believe in the No-Kill Millennium as it’s stated,” Pulliam adds. “Even though they worked as a group to send it to the City Council, they don’t believe in it. If I made a policy that the only animals that could leave the shelter were adoptable animals, we would have already achieved No-Kill—and they would crucify me.”

One animal advocacy group that does agree with the stated policy of putting the priority on saving adoptable animals is the organization that wrote it, Austin Pets Alive. Co-president Melody Putnam says her group focuses on animals that have been put up for adoption and whose twenty-one days of waiting for a new owner have expired. “Those are the animals that we target first to rescue,” she says.

One animal advocacy group that does agree with the stated policy of putting the priority on saving adoptable animals is the organization that wrote it, Austin Pets Alive. Co-president Melody Putnam says her group focuses on animals that have been put up for adoption and whose twenty-one days of waiting for a new owner have expired. “Those are the animals that we target first to rescue,” she says.

Most other rescue groups are less concerned with adoptable animals and more concerned with other factors. This is particularly true of breed-specific rescue groups, of which there are many. They are focused on saving the breed they are interested in, regardless of its classification. Pulliam tells a story about a woman who was determined to rescue a Bull Terrier (think Spuds McKenzie, the Bud Light spokesdog) despite the danger this particular bred-for-fighting animal presented. “A lady from Dallas wanted to take an animal that was vicious and I told her no and she was mad at me,” Pulliam says. “It was her breed and she was a rescue person and she would save her breed at all costs.”

Kathy Pardue of Austin Feral Cats says that in meetings with rescue groups, Pulliam has stated that the No-Kill goals could be achieved if the groups would take adoptable animals instead of the ones they are taking, although Pulliam says she has no personal preference.

“I think I’m going to have to reach consensus on what the mission is to be,” Pulliam says. “If the mission the community wants is to lower the euthanasia rate in general, that’s fine. I believe in that and I think that’s what these folks believe in. But that’s not what the resolution says…Let’s look at the plan and see what we want the mission of the shelter to be and then reconcile that with the City Council and get everybody on the same sheet of music.”

Meanwhile, TLAC continues by necessity to be a place of refuge and a place of death. It’s a combination adoption agency and prison complete with death row. Realizing that forty-nine percent of all animals that entered TLAC in the first nine months of the current fiscal year went out in a plastic bag, the ones selected to be presented for possible adoption are the picks of a mighty big litter. Dogs considered good candidates for adoption are placed in individual pens, where they will stay until adopted or for twenty-one days, at which time they will in many cases be killed. For every dog in a cage waiting for fate to smile, others will be killed and bagged. An animal’s chances of making it out of TLAC alive are just barely better than fifty-fifty.

Animal rescue groups contend the odds of surviving are practically nil for kittens and puppies that enter the shelter at less than eight weeks of age. If not euthanized they have difficulty surviving the stress, noise, and high propensity for respiratory disease in a facility that lacks the sophisticated ventilating systems of modern shelters. Kittens without their mother must be fed every two hours around the clock, something TLAC is not equipped to do, though cat rescue group volunteers can and often do take on that responsibility.

“People bring in a litter of kittens and think they will be adopted. They won’t. They will be killed,” says Pat Valls-Trelles, the self-professed TLAC watchdog. “It’s a dirty little secret how many animals will be killed down there.”

There are disclaimers on the door to warn people who bring in animals that they may be killed. Pulliam says the warning is also part of the paperwork people will complete to release an animal. Pulliam does concede that death awaits kittens and puppies not rescued. “If we can’t get them out of the shelter we euthanize them because their immune systems won’t tolerate the shelter,” she says. “We look for foster groups, but the percentage euthanized will be higher because older animals can stay in the shelter and not become ill.”

While TLAC officials and rescue groups may not agree on much, they all agree that the long-term solution is to do more of what Dr. Kathy Jones does just about every weekday morning: castrate male animals and spay females. The only animals that are supposed to leave TLAC intact are those too young or too sick to have surgery. People who take intact animals are required to sign an agreement to have the surgery done later.

To understand how crucial it is to make sure that pets can’t reproduce helter-skelter, consider the birth rates. According to the American Humane Society, by the age of five years, a female dog and her female offspring can produce 192 puppies, assuming two females per litter and two litters per year—and that doesn’t include all the offspring produced by her male puppies. Because there’s not enough humans to go around, this adds up to a great deal of unwanted puppies and dogs.

But dogs are pikers in the reproduction department compared to felines, says the American Humane Society. Allow two cats and their surviving offspring to breed for ten years and you will have produced more than eighty million cats, assuming two litters per year and 2.8 surviving kittens per litter.

These frighteningly high numbers are what causes so many resources to be devoted to stopping unwanted breeding. Spaying and castrating is the first and foremost mission of Animal Trustees of Austin. President Missy McCollough says, “We have spayed and neutered 25,000 animals in four years.”

Amber Rowland says a cat can go into heat and get pregnant as young as three months of age. “Unfortunately most people think they are supposed to wait until the cat is six months old,” she says. “A cat could already have had first litter by then. Not all vets have the tools and materials to do spay-neuter at an early age, so some don’t do it.”

Animal Trustees operates a low-cost Spay-Neuter Clinic at 5129 Cameron Road. They castrate male dogs for $25 ($10 extra if the dog weighs more than fifty pounds), spay female dogs for $30, castrate male cats for $15 and spay female cats for $20. They also provide low-cost vaccinations. The Clinic’s veterinarian, Amy Kastrisin, estimates that she alone has done 20,000 surgeries in the last four years.

Animal Trustees also spays and neuters sixteen to eighteen feral cats a week, a service provided free through a $5,000 grant that’s fast running out. These are wild animals. “They are never handled with human hands while conscious,” McCollough says. “We do most of the surgery for Austin Feral Cats.”

“We started Austin Feral Cats because we believe the only effective way of cutting down the unowned cat population is to trap, neuter and return (TNR),” says Kathy Pardue. “You neuter them, vaccinate them, and return them to their colony.” A feral colony is usually made up of an extended family of cats who will defend their territory and keep out other cats, Pardue says. “Eventually this will reduce the population because the colony will quit reproducing and quit growing and eventually will die out. If everyone was doing this all over the area, the unowned cat population would decrease.”

The U.T. Campus Cat Coalition operates on the same principle. Its sole purpose is to humanely control the population of feral cats (defined as undomesticated and unapproachable strays) that live on the main campus. Students abandon unneutered cats, which must then fend for themselves. The cats form colonies around abundant food sources and reproduce at incredible rates. At one time the University’s policy was to round up cats for killing at TLAC. In 1995, the Coalition convinced officials to allow them to take over and do TNR, plus M for manage. Volunteers feed and monitor the colony daily.

Missy McCollough says the same techniques have been used to manage colonies of feral cats in Austin neighborhoods overpopulated with reproducing cats.

The city not only castrates or spays nearly all animals before they are released but also contracts with the EmanciPet Mobile Spay and Neuter Clinic, operated by Ellen Jefferson, doctor of veterinary medicine, to provide free pet neutering and vaccinations for rabies. Additional services are available at nominal cost. For the past year, free clinics have been held four Fridays each month at posted locations in East Austin. Jefferson estimates she has spayed or neutered some 1,200 animals in this program at no cost to owners. She says the city pays $10,800 a year for forty-eight surgery days. Jefferson can perform up to forty surgeries a day on a first-come, first-served basis.

“I’ve been doing this for three years and I’ve gotten pretty fast at it,” she says. Most days she can take crank out the full day’s load in about six hours. The van has two surgery tables and forty-four cages and she operates on alternating tables.

In addition to EmanciPet, the city offers a voucher program for people on public assistance. For eight dollars (or pay what you can), someone on public assistance can have a pet spayed or neutered by local veterinarians, who get the small amount from the client plus an additional amount from the city. Vouchers are available at TLAC and city neighborhood centers.

Jefferson says one challenge faced in spaying and neutering, especially in low-income areas, is dispelling myths. Some people think they will make a lot of money breeding their pet. Some believe it’s best to let a female have a litter before spaying. Some think that castrating or spaying will change an animal’s personality. Some will refuse and purposefully breed and not care what happens to the offspring, she says. “It’s best to focus on people who want to get it done or who are uneducated, which is the majority of the problem,” Jefferson says.

A wild card in the pet population is the phenomenon of “puppy mills.” These are not quality dog breeders but operations that breed dogs in mass numbers for wholesale to the pet industry. (Reputable stores catering to pets, such as PetsMart, do not sell dogs or cats but do open their facilities to rescue groups that interview customers for adoptions.) Many puppy mills are characterized by overcrowding, filth, inadequate shelter, and insufficient food, water, and veterinary care. Last year, Animal Trustees of Austin was called to do an emergency rescue of fifty-two dogs found in an Austin area puppy mill. Missy McCollough wrote in the group’s newsletter that the dogs were found crammed into cages stacked on top of each other in a dingy little room, and published photos to prove it. A small Yorkshire Terrier named Scout was found with her muzzle taped shut to keep her from barking.

Another problem is backyard breeders who resort to selling the offspring on the side of the road, a practice that is being addressed by the Animal Advisory Commission. Commissioner Pat Valls-Trelles makes a distinction between quality purebred breeders, who will breed a female only a few times in her lifetime and carefully place the offspring, and the quick-buck operators who set up on roadsides and hope to get motorists to stop and buy on impulse. People who buy these roadside animals are part of the problem, Valls-Trelles says, because they encourage backyard breeders to stay in operation. Usually these animals are not vaccinated. The ones not sold often wind up at TLAC, she says.

A draft city ordinance will, if adopted by the City Council, add a new section to City Code 3-1-18 to make it an offense to sell, trade, barter, lease, rent, give away or display for commercial purposes a live animal on a roadside, public right of way, commercial parking lot, or at an outdoor sale, swap meet, flea market, parking lot sale or similar event. Such actions at flea markets or parking lots where the owner’s permission has been granted would be exempt.

Yet another problem is what’s known as the “collector,” referring to someone who starts out with good intentions and takes in a stray or two and winds up creating a labyrinth of filth and disease by letting the situation get completely out of hand. The Austin American-Statesman has reported at least two incidents in which more than a hundred animals were confiscated from a single residence, all of which wound up at TLAC’s doorstep.

The city’s fee structure approved each year by the City Council during the budget process is up for fine-tuning in ways that are causing the hairs to stand up on the back of animal rescuers’ necks.

Becky Rohne of Puppy Love Rescue is a member of the city’s Animal Advisory Commission and a member of the No-Kill Partners group that’s grappling with how to proceed on the No-Kill Millennium plan. “Right now, I would say the relationship with rescue (groups) and TLAC is close to an all-time low,” she says.

Rohne says that rescue groups fear that proposed fee changes coming as part of the next fiscal year’s budget will bring unintended consequences. One proposal would change what rescue groups must pay to take an animal out of TLAC. She says it’s an à la carte arrangement now. The groups pay $9 for an implanted microchip that will allow pet identification to be picked up with a scanning instrument, $6 for a rabies vaccination, and $5 for city registration tags for a spayed or castrated animal. The proposal would change the fee to a flat $20 for all animals, “and we may or may not get any workup on the dog at all,” she says. “The relationship is such that nobody is willing to go on good faith that they will do that. There have been real improvements and overtures made to open communication, but there’s a lot of distrust.”

Pulliam says setting the rescue fee at a flat $20 will save a lot of unnecessary bookkeeping and won’t affect the services rendered, which include a lot more than the microchip, rabies shot, and tags. “We provide wellness vaccine, a heartworm test for dogs, feline lukeumia and FIV tests for cats, Frontline treatment (flea and tick control), rabies vaccine, microchip, pet registration tag, boosters on wellness vaccines, and we deworm them or provide parasite treatment,” Pulliam says. She says these services are provided for all animals that can be treated. Kittens four weeks old can’t be treated and rescue groups aren’t charged, she says, nor are groups charged for severely injured animals or other animals with special needs. Pulliam says she’s meeting quarterly with rescue groups and hopes to reach consensus for written policies on rescue fees that can be applied evenhandedly.

Valls-Trelles complains that the daily boarding fee, now $5, would be hiked to $10, a fact that Pulliam confirms. They differ on the effect. Valls-Trelles says doubling the boarding fees works a hardship on poor people. She says the fee was lowered from $8 a day to $5 by the City Council in 1999. “My fear is latest proposal in new budget will make it even less affordable because low-income people can’t afford to get them out. It goes contradictory to the No-Kill plan,” she says.

Pulliam says TLAC will work with anyone who can’t afford the fees. TLAC will set up payment plans for working people and community service plans for homeless people whose pets have been confiscated. “There are lots of ways we can work with low-income individuals to make sure animals can go home alive regardless of what our fee structure is,” she says.

Another bone of contention over fees is that currently the annual registration fee—$5 for a castrated or spayed animal, $15 for an unaltered animal—would be changed to a flat $10 per animal, fixed or not. Rohne thinks that sends a signal that fixing an animal isn’t important. She says the current differential motivates people to get their animals fixed.

Pulliam says the differential doesn’t work in Austin, in part because the city has not made it mandatory that vets register the animals they vaccinate. “In other communities, it’s mandatory that every vet sell registration tags when they do an annual rabies vaccination,” she says. In San Antonio, Pulliam says, an animal owner doesn’t get to choose not to follow the law. Further, the annual cost savings on lower fees for fixed animals is not enough to warrant laying out what a private vet usually charges to spay or neuter, Pulliam says, as it might take ten years to recover the outlay.

“My focus on leveling (the registration fee) is to get pets registered,” Pulliam says. “I will work on programs to spay-neuter other ways, like the EmaniciPet van. I’m getting a heck of a lot more done through EmaniciPet than through registration.”

The most important point to remember about registration is that a registered pet is far more likely to be reunited with its owner after it’s picked up by animal control officers or brought to TLAC by another citizen. One consultant, Bob Christiansen of Atlanta, estimates that only twenty-seven percent of Austin’s dogs are registered. TLAC’s statistics for the first nine months of the current fiscal year show that only thirteen percent of animals were returned to their owners.

Christiansen is the author of numerous books, including Save Our Strays: How We Can End Pet Overpopulation and Stop Killing Healthy Cats and Dogs and Choosing and Caring for a Shelter Dog: A Complete Guide to Help You Rescue and Rehome a Dog. He advocates vigorous pet registration combined with implantation of microchips and visible tags. “A microchip program would return lost pets home, would reduce the stress on shelters, foster responsible pet ownership, provide a means to track congenital diseases and track owners of vicious dogs who allow their dogs to roam and cause bodily harm to humans,” he wrote on his web site. Nationally, such a program could save millions of pets’ lives, he states. Christiansen presented a proposal to TLAC last November that he claims would increase license compliance and generate revenue for programs that will save animals’ lives.

Pulliam says the proposal looks interesting but since Christiansen is not the sole vendor of such programs, she is putting out a Request For Proposals to solicit offers. “I’m putting out an RFP to take one up on it,” she says.

The bottom line is that Pulliam is on the hot seat. Animal rescue groups haven’t invested their trust in her yet. For about ten months she has headed an organization with a long and sordid history, one that is still far from achieving what is needed. TLAC’s facilities are nearly a half-century old. They are poorly designed, a place where disease may spread rapidly among the up to 700 live animals that may be on the premises at any one time. The buildings also sit in a 100-year floodplain with storm drains on each end connected to the city’s wastewater system. In 1998 employees and volunteers had to don galoshes and wade through high water tainted with raw sewage to carry animals to dry ground. “If we had a major storm we would have to turn them loose so they would not drown,” Pulliam says of the animal population.

Consultants Gates Hafen and Cochrane Architects of Boulder, Colorado, are working on a master plan due October 1 for a new facility, Pulliam says, and Assistant City Manager Betty Dunkerley is looking for suitable land. “It could be an animal destination in a parklike environment,” Pulliam says. “We hope to build it in three to five years.”

Meanwhile the mission is to make do with the antiquated facilities and tweak programs for best results. Part of that tweaking has been adjusting the number of employees working with rescue groups. Becky Rohne says that “sends a message to rescue they’re not important or the goal of the shelter is not to work with rescue.” This despite the fact that rescue is saving far more animals than TLAC is placing through adoption. Pulliam says one of the three positions she had for rescue coordinators was initially frozen when sales tax revenue slowed. “I can rescue the same number with two people as with three people,” she says. She says the extra person didn’t produce more rescues, although it may have made TLAC a friendlier place for rescue groups.

Pulliam operates TLAC on a $3 million budget with ninety positions authorized, and she will not lose any in the coming budget, she says.

For the director caught in the crossfire, the job is to try to look beyond the needs of rescue groups alone and keep an eye on the bigger goal. “We won’t stop euthanasia unless we get out there an do education,” she says.

The pet-owning public could do much to stem the slaughter by taking the health and welfare of our animals more seriously, and by recommending that friends looking for dogs or cats always adopt from TLAC and other shelters and rescue groups instead of patronizing roadside peddlers or flea market fly-by-nighters.

Most importantly of all, we should castrate and spay our pets, and encourage our friends and neighbors to do likewise. Pat Valls-Trelles says the highly successful campaign that changed our nation’s attitudes about drinking and driving is the perfect model for dealing with pet overpopulation. “Friends don’t let friends breed and create an unwanted litter,” she says.

Ken Martin, editor of The Good Life and Gusto magazines, is co-guardian of a black Labrador retriever adopted from TLAC and two cats adopted from rescue groups. We made up the names of the animals shown in the accompanying photographs. These particular animals may or may not be available for adoption by the time you read this.

Fleet Footed Canine Catcher

“Every owner of a dog and any person having charge, care, custody or control of any dog shall restrain such dog from running at large.” Further, “Employees of the city…are hereby authorized and empowered to enter upon any land, premises or public place and to take up and impound any dog which is observed by such employees to be running at large.”

—City Ordinance 3-3-2

Call them dog catchers or animal control officers (their official titles) Austin’s crew of fourteen canine catchers stay busy-especially in hot spots like East Austin, which accounts for a disproportionately large percentage of the dogs picked up. Austin has a huge problem with stray animals and animal control officers beat the streets daily to hunt them down. The officers brought in a total of nearly 12,000 dogs from October 1, 2000, through June 30, 2001, about seven of every ten animals taken into Town lake Animal Center (TLAC). There is no law on the books about stray cats and these officers rarely get involved with felines unless they bite someone.

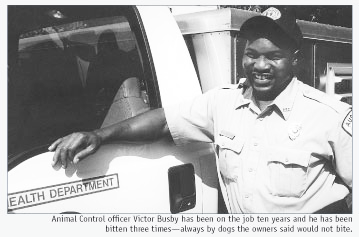

On July 17, it’s not even eight in the morning when Victor Busby and Lissa Doggett steer their Ford XL 250 trucks out of the TLAC facility and head east on Cesar Chavez. They will patrol the entire area of Austin north of Town Lake and east of I-35. It’s another hot summer day. Busby and Doggett are wearing the city uniform: shorts, short-sleeved shirts and shiny silver badges. At three minutes after the hour they spot two loose dogs and pull up to a frame house at 1802 New York Street. They park the trucks, slip on gloves, grab nets affixed to poles, and move up the driveway. A brindled pit bull-chow mix sprints around Busby and heads toward the street but Doggett nets the animal. Busby nabs the playmate, a brown pit-chow mix, and within four minutes both are loaded. The trucks are ready to move, as soon as Busby, already sweating, picks a tick off his leg. At twenty minutes after the hour they’ve bracketed two more strays in the 1900 block of Riverview Street. They trap one against a backyard fence. As Busby lifts his catch into the truck the dog lets loose its bowels, but misses. “Most of the time they’ll poop on me when I carry them like I did,” Busby says.

On July 17, it’s not even eight in the morning when Victor Busby and Lissa Doggett steer their Ford XL 250 trucks out of the TLAC facility and head east on Cesar Chavez. They will patrol the entire area of Austin north of Town Lake and east of I-35. It’s another hot summer day. Busby and Doggett are wearing the city uniform: shorts, short-sleeved shirts and shiny silver badges. At three minutes after the hour they spot two loose dogs and pull up to a frame house at 1802 New York Street. They park the trucks, slip on gloves, grab nets affixed to poles, and move up the driveway. A brindled pit bull-chow mix sprints around Busby and heads toward the street but Doggett nets the animal. Busby nabs the playmate, a brown pit-chow mix, and within four minutes both are loaded. The trucks are ready to move, as soon as Busby, already sweating, picks a tick off his leg. At twenty minutes after the hour they’ve bracketed two more strays in the 1900 block of Riverview Street. They trap one against a backyard fence. As Busby lifts his catch into the truck the dog lets loose its bowels, but misses. “Most of the time they’ll poop on me when I carry them like I did,” Busby says.

They answer a complaint call at 1703 Riverview, where a small dog has been hiding under the elevated house. “I’ve been feeding this dog three days and I don’t want a relationship with this dog,” the woman says. Busby tries to net the pooch but it sprints under the house. He promises a trap will be delivered to capture the dog. “If there’s no food outside the trap, she’ll go in,” Busby tells the woman.

Soon, dispatchers direct Busby and Doggett to 301 Navasota to speak to a complainant. The area proves inaccessible by truck due to utility construction. While circling for access, they spot a large Rottweiler and another stray on East Fourth Street. They bracket the dogs, parking on either side. Suddenly the Rottweiler is airborne, sailing over a chain-link gate more than six feet tall with the ease of a gazelle. The gate is locked. The rest of the fence is made of eight-foot-tall sheets of plywood. No one answers the bell. The Rottweiler stands inside the fence, barking incessantly. They post a notice on the gate, spelling out in both English and Spanish that impoundment of the animals can result in citations and fines or both. The notice doesn’t indicate how much the fines are, but they are hefty. Busby says they cost $155 each and you can rack up three in one whack: one for an animal running at large, one for failure to vaccinate the animal, and one for the animal not wearing city pet registration tags. On top of that, there’s a $55 impoundment fee and up to $31 in other fees. If the dog is kept overnight, that will add another $5 a day for boarding.

Busby says a first-offender’s program will allow the owner to pay $25 and go to a class if registration and vaccination are proven within seventy-two hours. It’s a program that works much like going to defensive driving school to erase a speeding ticket. A dog owner can do this once a year. “We don’t like to cite people who can’t afford it,” Busby says. “We give them one chance if they’re amenable and put it into the computer. We’ll even warn them twice. Three times and you’re out-the dog’s going to get a citation.”

Busby and Doggett move to the 301 Navasota complaint and the offending dog, a gray-and-white Australian Shepherd mix squirts by Busby’s extended net. Busby drives several blocks trying to head off the dog but it is too fast. At Fifth and Waller he gives up the chase. Meanwhile, Doggett radios that she has spotted two dogs at 1405 E. Fourth Street. Busby joins her, wheeling into the alley at the end of a long chain-link fence that borders the side of the yard. Doggett moves in from the other end. The two dogs quickly wriggle under the fence to join others inside. Busby posts a notice to warn the owner to fix the fence so the dogs can’t get out again.

It’s still not nine yet when the radio crackles with a call sending them far north in East Austin. On the long cruise Busby says he’s been in this job ten years now and has been bitten three times, all three times when the owner said the dog would not bite. “Every dog with teeth will bite. That’s my motto,” he says. To emphasize the point, he says that a couple of days earlier he went into a yard with two dogs that a woman said would not bite. “They tried to eat me up, like Cujo,” he says, referring to the Stephen King novel and horror movie in which a New England family is terrorized by the family dog, a rabid St. Bernard.

Doggett knows all too well that dogs will bite. In April, a white pit bull she was trying to woo away from the trash he was sniffing clamped down on her left arm, just above her watch band, and bit halfway through her arm. Doggett told the Austin American-Statesman that neighbors said the dog had been trained to attack anyone in uniform, although the dog’s owner denied it. “She fed him her arm to protect her neck,” Busby says. “I hit him with the net. He was so cool. He let go of her and walked off. She was bleeding. Our first objective when there’s a bite is to get the animal. I netted him. Another unit took her to the emergency room.” Doggett says the wound took thirty days to heal, during which time she had to do physical therapy. “I could not bend back my fingers till I got therapy,” she says.

The city filed dangerous dog charges against the owner of Cain, the pit bull that bit Doggett. Busby says the owner could be fined up to $4,000 and once a dog is declared dangerous the owner must get a liability insurance policy of $100,000. The animal must wear a large tag identifying it as a dangerous dog and it must be kept in an enclosure inspected by the city. The Statesman reported that twenty-three dogs in Austin are registered as dangerous.

An animal that bites or breaks the skin must be quarantined for ten days if it can’t be shown to have a current rabies vaccination, says Amber Rowland, community awareness coordinator at TLAC. If the animal shows no symptoms during quarantine, it is presumed not to be rabid. While Austin has no problem with rabies among dogs and cats (bats are another story), the entire state is under a rabies alert because of a high incidence, she says. That’s why Austin requires an animal to be vaccinated annually, even though vaccines might be good for three years.

Back on the beat, Busby and Doggett pull up to the complainant’s apartment at 7419 Vintage Hills, where three red chows had been reported. A woman tells them, “Y’all too late. The dogs done run off.”

Just then the dispatcher reports a call at 2901 Goodwin, where an aggressive dog had attacked a woman and her dog the day before. That’s back down south, but Busby says if they can get there within an hour the dog will probably still be there, as dogs tend to stay in the neighborhood they live in. As they are headed in that direction they spot two small dogs with tags in a driveway. As Bubsy and Doggett stop, the pooches trot around the end of the fence and back inside the yard at 2301 E. Ninth at San Saba. Doggett nets one of the dogs, a brown Chihuahua mix, and traps it against the side of the fence and holds it. Busby runs the tags through dispatch. It’s been recently vaccinated by EmanciPet, a mobile veterinary service that the city pays to stop at selected East Austin locations four Fridays a month, providing free spay and neuter service and free rabies vaccinations. Residents are summoned from the house, but they don’t speak English. Doggett and Busby try to communicate in their limited Spanish. They warn the woman to keep the dog tied, since it can get out of the fence. “If the dog has city tags, we give them one free pass,” Busby says. “It’s like a Get Out of Jail Free card.”

Shortly before ten, the dispatcher directs them to 2506 Lehigh Drive to assist a constable. They arrive to find a front yard filled with furniture from a court-ordered eviction. The constable leads them through the trashed-out house to the back yard where there are two ducks and two guinea hens. They nab the ducks but the hens take flight. Busby returns with a net and as he wiggles between the house and an air-conditioning unit, a hen takes flight and gets caught in his net. “I didn’t even see her,” he says.

On the way to a pit stop for gasoline, Bubsy says, “We’ve come a long way. We used to drive pickups with a dog cage on the back.” The trucks he and Doggett are driving now have air-conditioned pens. “We see dogs now, but nothing like it used to be. It’s amazing we have gotten the city under control.”

The next call is at 1104 Saucedo Street, where a female pit bull is reportedly foaming at the mouth. A man denies knowing anything about the dog, but another man says that’s his brother and he’s done this before. “He gets a dog and doesn’t feed it.” The man says the dog is sick but there’s no money to take it to a vet. One side of her stomach is hanging down, apparently filled with fluid. “We don’t want to do this but it’s a last resort,” he says, reluctantly signing the release proffered by Doggett so that Busby can take the dog.

Finally arriving at 2901 Goodwin, they find two dogs chained inside the back yard. A sleepy boy of thirteen answers the door. No adults are home. Busby gives him a notice that the dogs need registration tags.

Shortly after eleven they arrive to answer a complaint at 5608 Ledesma Road. The two dogs in the yard take off. Around the corner, Busby snares one of them. The other escapes into a forest a block away. Busby goes back to tell the complainant, who replies, “Thank you, man.”

After a brief lunch stop, Busby answers a call at 1204-C Salina Street. A woman who lives in an upstairs garage apartment can’t care for her dog in the yard downstairs due to her surgery. She’s in tears but asks him to take the dog. He goes in the gate and closes it but the dog escapes through another opening.

Busby, now thirty-one, started the job five days before he turned twenty-one. He worked inside the pound first, and got the animal control job when it opened up. What kind of training did he get? “You really don’t get any, except on the job,” he says. He says he started the job at $7.45 an hour in 1991 and after six years was making $10 an hour, the maximum at the time. After a survey of what other cities paid animal control officers, the top tier was hiked to $14 an hour, which is about what he makes now.

We arrive at Town Lake Animal Center at half past noon. Doggett’s already there and has unloaded. Busby takes animals out one at a time, carries them inside and scans to see if they have a microchip and weighs them, then puts them in a cage. He brought in three dogs this morning. Doggett brought in three more, plus the two ducks and a guinea. Inside they sit at a computer to enter the data for each animal into the Chameleon database, which assigns an animal identification number for each. Doggett and Busby say they bring in about 250 dogs apiece each month. They beat the streets, snaring loose animals to bring order because owners are not holding up their responsibilities in many cases. It’s not the animal’s fault.

“Pound dogs are good,” says Busby. He believes that animals adopted from TLAC know how close they came to being killed and make excellent pets. “They were on death row and they know,” he says. “Give them a little love and they’ll die for you.”

Humane Society Does It Right

The Humane Society/SPCA of Austin and Travis County opened its current facility at 124 W. Anderson Lane in 1994. The City of Austin had forced the Humane Society to give up operation of the Town Lake Animal Center (TLAC) in late 1992. This was a period of bad blood between the city and the Humane Society, but it turned out to be a blessing for the Humane Society, whose mission was at odds with the fact that it was running a gas chamber at TLAC, which killed animals by confining them in a compartment and then pumping in carbon monoxide. The $1.6 million the city paid to the Humane Society for the buildings it owned on city land at TLAC gave the organization a new lease on life.

Today the Society’s 15,000-square-foot facility has the luxury of picking and choosing the dogs and cats it accepts. There’s a two-week waiting list just to bring an animal in, says Dineen Heard, public relations director. TLAC, by contrast, must accept anything that’s brought in, twenty-four hours a day, every day. Alligators. Ferrets. Pythons. Rats. There’s no telling what will turn up at TLAC. Of course, people don’t always play by the Humane Society’s rules. Staff often finds boxes on the front porch or out back.

Dogs are given a pre-adoption temperament test and if they don’t pass the owner must reclaim them or take them to TLAC. The test was devised by staff behaviorist Amy Boyd. Animals are screened for sociability, friendliness, aggression, and other traits that might prove undesirable in an adopted pet. “We pull their ears and tails because a toddler will,” she says.

People relinquish their companions for all sorts of reasons, Heard says. They’re moving. They have a new baby. They just got divorced. They are elderly and can no longer care for the animal. Because the bulk of animals taken were relinquished by owners who fill out a fifty-two-question background form, the Society has a detailed behavioral history on most of its animals.

Dogs and cats accepted are prepared for adoption with spaying or castration, vaccinations and a complete workup. Adoption counselors attempt to steer prospective families to dogs that fit the adopter’s lifestyle. “We strive to make a match for life,” Heard says. “We can turn people down for a specific animal.”

The Society functions in some respects like a rescue group, taking selected animals out of TLAC that might otherwise die. For the year that ended September 30, 2000, the Society took in a total of 2,359 animals, of which 443 were transferred from TLAC, Heard says. The rest were accepted from the public. Only fifteen animals were euthanized that year.

Dogs have kennel cards that are generally more detailed than the ones at TLAC, complete with color codes to indicate what level of training a volunteer must have to work with the animal and a list of its behavioral traits. The volunteer dog handlers make up the Behavior Rehoming Adoption Training Team.

Volunteer coordinator Dan Morris says he has a crew of about 150 volunteers who work at least two hours a week, a number he keeps building on with volunteer orientation classes offered monthly.

The front of the facility includes a “real life room” with couch and appliances to give adopters a chance to interact with an animal in a homelike environment. People who already have a dog and want to adopt another must bring in the dog to make sure the two will get along okay.

“We keep dogs as long as it takes to find a home if they remain physically and mentally healthy,” Heard says. “Some go kennel crazy, spinning in circles, chewing on their paws, pacing repetitively. If we feel an animal is suffering or becoming dangerous, we will euthanize it or transfer it to a rescue group.”

One outstanding rescue facility is the nonprofit Southern Animal Rescue Association in rural Seguin. This is a 580-acre, no-kill facility where only terminally ill animals suffering with no chance of recovery are killed. No animal is killed for convenience. Adoptive homes are sought but failing that, the animals have homes for life. It currently houses 400 dogs and 100 cats, plus a couple of hogs weighing about 800 pounds apiece.

Outside the Humane Society facility sits a large truck and trailer that provides a mobile adoption unit. Like the van owned by EmanciPet, this big rig was donated by Michael McCarthy, a former Humane Society board member. The mobile unit has sixteen dog cages and six cat cages. Recently parked at a Tinseltown Theater that was showing Cats & Dogs, the unit netted two adoptions on-site. Plans call for rolling up to Round Rock for a baseball game played by the Express. Fill out the adoption forms, pass the interview, pay the $75 (the same adoption fee as TLAC) and you can go home with a pet.

There are scores if not hundreds of volunteer organizations working to assist animals in this area. Each has its own mission. Some rescue groups take animals relinquished by their owners while other groups may refuse on the theory that it only encourages irresponsible behavior. Virtually all of these organizations need help in terms of cash, volunteers or other resources, and most have animals ready for adoption.

The organizations listed either responded to an invitation to have the information published or were located on the web. Because some organizations don’t have sufficient resources, a few of those listed declined to publish a phone number. There are many other organizations that work in a similar fashion in this area.

American Curl Rescue Project, (512) 336-8474, www.sarcenet.com.

Animal Trustees of Austin, (512) 302-0388, www.animaltrustees.org.

Animal Trustees of Austin Spay-Neuter and Vaccination Clinic, (512) 450-0111, www.animaltrustees.org.

Austin360.com Pets of the Week (listings for numerous shelters and rescue groups), www.austin360.com/services/pets/pets_ofthe_week.html.

Austin Animal Advisory Commission, (512) 708-6080, www.ci.austin.tx.us.

Austin Boston Terrier Rescue Inc., http://home.houston.rr.com/rector.

Austin Feral Cats, www.austinferalcats.org.

Austin-Houston Hound Rescue, (Beagles, Bassetts, other hounds), www.houndrescue.com/austindog.htm.

Austin Aussie Rescue, (512) 303-1987, www.petfinder.org/shelters/TX182.html.

Austin Lost Pets, www.austinlostpets.com.

Austin Parks and Recreation Department’s Leash-Free Areas, (512) 974-6700, www.ci.austin.tx.us/parks/dogparks.htm.

Austin Rescue, home of shelter-friendly rescue groups

Austin Pets Alive, (512) 452-5790

Austin German Shepherd Rescue, (512) 413-0589, www.austingermanshepherdrescue.org.

Austin Siamese Rescue, (512) 288-1617, www.siameserescue.org.

Bastrop Humane Society, (512) 303-3924.

Blue Dog Rescue, www.bluedogrescue.com.

Border Collie Rescue Texas Inc., (800) 683-8703, www.bcrescuetexas.org.

Bow Wow Rescue Save Pets Society, (512) 272-8015

Capitol of Texas Siberian Husky Club

Cedar Park Animal Control, (512) 258-3149, www.petfinder.org/shelters/TX200.html.

Charlyne’s Pound Puppies, Thorndale (512) 898-5237, or in Austin (512) 335-1417.

Central Texas SPCA, Leander, (512) 260-7722

Central Texas Dachshund Rescue, www.ctdr.org.

Central Texas Welsh Corgi and Great Dane Rescue, (512) 442-4689.

Cocker Rescue of Austin, (512) 282-3009, www.cockerrescue.homestead.com.

Collie Rescue Austin, (512) 515-5494 or www.austincollies.org.

Dreamtime Sanctuary, Elgin, (512) 281-4572, www.dreamtimesanctuary.com.

Emancipet Mobile Spay-Neuter Clinic, (512) 587-7729 or www.emancipet.com.

Friends of San Marcos Animal Shelter, (512) 396-6180.

Georgetown Animal Shelter, (512) 930-3592, www.petfinder.org/shelters/TX34.html.

German Shepherd Rescue Central Texas, (512) 264-2478, [email protected].

Gold Ribbon Rescue (Golden Retrievers), (512) 659-4653, www.grr-tx.com.

Greyhound Rescue Austin, (512) 288-0068

Hays County Animal Control, San Marcos, (512) 393-7896, www.co.hays.tx.us.

Heart of Texas Lab Rescue, (512) 259-5810, www.hotlabrescue.org.

Helping Hands Bassett Rescue, http://www.hhbassetrescue.org.

House Rabbit Resource Network, (512) 444-EARS, www.rabbitresource.net.

Humane Society of Williamson County, Leander, (512) 260-3602, http://hswc.net.

Humane Society-SPCA of Austin and Travis County, (512) 837-7895, www.austinspca.com.

Jack Russell Rescue, (512) 273-2412, www.terrier.com.

Lago Vista PAWS, (512) 267-6876 or www.lvpaws.org.

Mastiff Club of America Rescue Services (512) 419-0944 or www.conceptsdesign.com/mastiff.

Mixed Breed Rescue, (512) 260-0462, www.geocities.com/mixbreedrescue. (This link is no longer functional.)

PAWS Animal Shelter, Kyle, (512) 268-1611, http://paws.home.texas.net/morepaws.html.

Pet Helpers, (512) 444-PETS, www.pethelpers.com.

Pet Protection Network, 444-8380.

Puppy Love Rescue, (512) 447-1785, www.puppyloverescue.org.

San Marcos Animal Shelter, (512) 393-8340

Shelter Rescue, (512) 288-4480.

Shiba Inu Rescue of Texas, (512) 505-5349, www.geocities.com/iluvshibas/rescue.html.

Southern Animal Rescue Association, Seguin, (512) 460-5083 days, (512) 288-1879 evenings, www.sarasanctuary.org.

Southern States Rottweiler Rescue Inc., (512) 912-8294, http://ssrottweilerrescue.org.

Spindletop American Pit Bull and Staffordshire Terrier Refuge, (512) 918-9570, http://austinpitbullrescue.homestead.com/home.html.

Texas Great Pyrenees Rescue

Theo’s Home, (512) 292-7386.

Town Lake Animal Center, (512) 708-6000, www.ci.austin.tx.us/animals.

Travis County Environmental Health Services-Animal Control, (512) 469-2015, www.co.travis.tx.us.

Underdog Rescue, (512) 931-2771, www.underdogrescue.com.

UT Campus Cat Coalition, (512) (5121) 471-3006, www.ae.utexas.edu/cats.

Wee Rescue (Lhasa Apso and Shih Tzu), (512) 292-1700

West Highland White Terrier Club of Greater Austin, (512) 388-0645, www.austinwesties.org.

The wide margin of victory for the SOS Ordinance showed there was abundant public support to protect the environment. That sentiment was roused again in 1993 to sweep onto the City Council both Brigid Shea, founding director of the SOS Coalition, and Jackie Goodman, former president of the Save Barton Creek Association (SBCA).

The wide margin of victory for the SOS Ordinance showed there was abundant public support to protect the environment. That sentiment was roused again in 1993 to sweep onto the City Council both Brigid Shea, founding director of the SOS Coalition, and Jackie Goodman, former president of the Save Barton Creek Association (SBCA). The SOS Alliance was adamantly opposed to the proposal. Robin Rather warned the council it was “trading predictability for chaos” if it bypassed the SOS Ordinance. Hampering the SOS Alliance’s argument, however, was the defection of engineer Lauren Ross, who had helped draft the very SOS Ordinance that would be overridden if the Forum PUD was approved. In working for the Forum PUD developer, Ross proposed to use innovative engineering solutions she said would protect the aquifer.

The SOS Alliance was adamantly opposed to the proposal. Robin Rather warned the council it was “trading predictability for chaos” if it bypassed the SOS Ordinance. Hampering the SOS Alliance’s argument, however, was the defection of engineer Lauren Ross, who had helped draft the very SOS Ordinance that would be overridden if the Forum PUD was approved. In working for the Forum PUD developer, Ross proposed to use innovative engineering solutions she said would protect the aquifer. Which gets at the heart of the growing dilemma for the environmental movement. Austin environmentalists were good at organizing and raising hell when the city was ruled by a council that was anything but green. So good, in fact, they got their own candidates elected. But electing candidates friendly to the cause has not cured all the problems they perceive with environmental protection. The problem is exacerbated when the environmentalists can’t present a unified front, leaving the council to pick and choose which environmental voices to heed, and which to ignore.

Which gets at the heart of the growing dilemma for the environmental movement. Austin environmentalists were good at organizing and raising hell when the city was ruled by a council that was anything but green. So good, in fact, they got their own candidates elected. But electing candidates friendly to the cause has not cured all the problems they perceive with environmental protection. The problem is exacerbated when the environmentalists can’t present a unified front, leaving the council to pick and choose which environmental voices to heed, and which to ignore.