About 15,100 words

Photography by Barton Wilder Custom Images

The clinic called with bad news about the pain. A CT (computed tomography) scan indicated a serious case of appendicitis and Claudia Sperber of East Austin needed to go straight to the emergency room at Seton Medical Center.

“I sent a friend to get the test results while I went directly to the ER (emergency room),” Sperber told The Good Life. “I waited not too long, and got an exam within thirty minutes. A surgeon came in to do the exam. He was unimpressed. He didn’t pay attention. I didn’t have the test results to show him, and he discounted my experience.”

When the friend arrived with the test results, “there was a sudden attitude adjustment” and the hospital promptly sent her into surgery. “The surgeon came in with the phone glued to his ear and they were setting me up for surgery. He ran a form by me. Said the surgery would be exploratory because we didn’t know what the problem was. When I mentioned the appendicitis, he asked, ‘How many appendectomies have you done?'” At this point, it was Sperber who was unimpressed. Nevertheless the surgeon removed her appendix with no complications.

Surveys among all industries tend to show that people today are less attached to a specific brand or company, more suspicious, and want to have greater control over their lives. For medicine, this is a sea change and many doctors and hospitals continue to struggle with the high level of participation patients want to have in their own care. That participation starts with the decision about which hospital to choose, and continues throughout the hospital stay. The Good Life investigated ways to choose the best local hospital, and then stay an active participant in your care.

Hospitals are not all the same

Historically, patients have primarily relied on their doctors to direct them to a particular hospital. But today, with the help of your health plan and a widening range of online services and government databases, you can participate in that choice directly. And the increasing range of information about our local hospitals shows that they are not all the same.

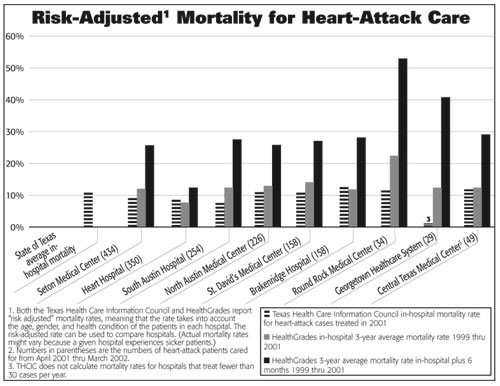

According to HealthGrades, a national company that provides healthcare quality ratings, Texas hospitals rank poorly compared to other states. “On average, you have a 54.9 percent increased chance of dying if you have an angioplasty or other percutaneous (through the skin) coronary intervention in Texas rather than New York,” said Samantha Collier, HealthGrades vice president of medical affairs. HealthGrades recently ranked Texas thirtieth overall for hospital care (based on outcomes for five procedures and conditions), and forty-first for procedures to correct a blocked artery.

But of course you can find a good hospital here. In line with more than a hundred studies, hospitals with a higher volume of a given surgery also tend to have a lower mortality rate for that surgery. This gives Central Texas residents something very concrete to look for before selecting a hospital.

For example:

Balloon angioplasty—This is a common surgical treatment for heart disease. More than 2,700 people underwent balloon angioplasty in Central Texas hospitals between April 2001 and March 2002. Those who went to The Heart Hospital of Austin—which conducted significantly more of these procedures than any other area hospital—enjoyed a better than expected mortality rate (fewer deaths), a shorter hospital stay, and lower average charges than patients at other area hospitals, according to reports published by the Texas Health Care Information Council (THCIC) and the Texas Business Group on Health (TBGH), a coalition of businesses that purchase healthcare for their employees.

Mortality rates for this procedure were not unexpectedly high at any area hospital, and both South Austin Hospital and Seton Medical Center performed more than 400 of these surgeries between April 2001 and March 2002. The TBGH, which produces several “report cards” on hospital performance, considers any hospital doing more than 400 of these surgeries to be a high volume hospital likely to have better outcomes.

“Practice makes perfect,” says Marianne Fazen, TBGH president and chief executive officer (CEO). “We don’t rate hospitals with fewer than seventy-five procedures, but we also don’t want people to go to those low-volume hospitals. Practice is the key. The high-volume hospitals have better systems, better processes in place. And we are in the business of driving business to the best performers.”

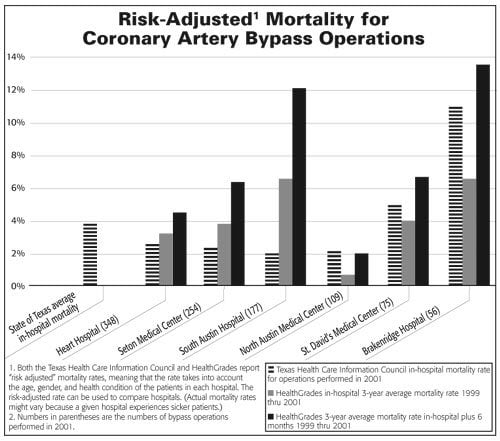

TBGH, HealthGrades and the Texas Health Care Information Council (THCIC) all report “risk adjusted” mortality rates, meaning that the rate takes into account the age, gender, and health condition of the patients in each hospital. The risk-adjusted rate can be used to compare hospitals. (Actual mortality rates might vary because a given hospital experiences sicker patients.)

Congestive heart failure—Hospitals that perform well on balloon angioplasty also tend to perform well on other measures of heart disease treatment. After adjusting mortality rates for the different kinds of patients that local hospitals treat, the THCIC reports that both Heart Hospital and South Austin Hospital have mortality rates significantly lower than the state average for patients with congestive heart failure (2001 data).

Coronary artery bypass—More than 1,000 people underwent coronary artery bypass operations in Austin hospitals in 2001. Heart Hospital, Seton Medical Center, and South Austin Hospital hosted three-quarters of them, and these hospitals all demonstrated mortality rates below the state average.

By contrast, the lowest volume hospital, Brackenridge, shows risk-adjusted, in-hospital mortality rates higher than the state average. Seven out of the fifty-six people who got this surgery at Brackenridge died (one in eight), compared to only five of the 254 who died at Seton Medical Center (one in fifty). Risk-adjusted mortality at Brackenridge for this complex surgery was, in fact, nearly three times the state average in 2001—a statistically significant difference—and the mortality rate had increased in both 2000 and 2001.

“One would expect that,” says the TBGH’s Fazen. “I am not surprised if a hospital that is not a specialty hospital in cardio, that has a low volume of procedures, doesn’t perform as well.”

Pat Hayes, chief operating officer of Seton Healthcare Network, which manages the city-owned Brackenridge Hospital, agrees that volume matters for complex procedures. “You can feel really great about going any place where your doc had a good team that did a high volume of procedures,” she told The Good Life. “Volume is a factor, there’s no question about it.

“As a matter of fact, we had a transplant program at Brackenridge Hospital that is on hold because the volumes weren’t high enough, so we didn’t want to be in that business,” Hayes said. “On the other hand, we have a new Brain and Spine Center, and we made a decision to move the work from Seton Medical Center over next to the Trauma Center at Brackenridge to aggregate the volumes in an area where we think we can get the highest level. I think if you looked at the numbers, and said pick a place for neurosurgery in the Seton system, I’d say Brackenridge. If you said pick a place for cardiac surgery in the Seton system, I’d say Seton Medical Center. And not everything is at that level of complexity. Pick a place to get your tonsils out, it’s probably okay anywhere.”

The risk-adjusted mortality rate for coronary artery bypass surgery at St. David’s Medical Center, another low-volume hospital, was somewhat higher than the state average but within the statistically predicted range. And on many of the indicators reported by the state, almost every hospital in Austin conducts too few procedures to reasonably report risk-adjusted mortality rates. (See accompanying article, “Some Procedures Rarely Done in Austin”.)

Jon Foster, chief executive officer of St. David’s HealthCare Partnership—a partnership between the not-for-profit St. David’s HealthCare System and Hospital Corporation of America, which operates four area hospitals—disputes the correlation between volume and quality of care.

“Certainly there’s some logic saying if a place does more of these they must be more proficient at it,” Foster told The Good Life. “The problem I have with that is the data doesn’t show it. North Austin Medical Center in our partnership doesn’t do an enormous volume of open heart surgeries but their outcomes are sterling.”

North Austin Medical Center hosts a modest amount of heart surgery, but all report card information from HealthGrades and THCIC is favorable.

Foster believes that the surgeon’s experience is a more important factor. “It has more to do with the skill of your surgeon, the skill of your anesthesiologist, and the skill of your nursing staff and your perfusionist than it does the volume. And so what I would want to know more than anything is that the surgeon has done a lot of these. Do you want to go to a hospital that has done a thousand open-heart surgeries but get the surgeon who is doing his first one on you?”

Unfortunately, there is no public information on mortality rates by surgeons in Texas, and very little information available about the quality of physicians generally. The Texas State Board of Medical Examiners will release information about physicians who have been disciplined, but even this information is likely to be old because physician discipline is subject to an extensive appeal process.

Coronary artery bypass operations are major surgery with major costs. Average billed charges for an average stay, which varies from hospital to hospital, ranged from a high of $70,438 at South Austin Hospital to a low of $40,491 at Heart Hospital—the hospital with one of the best mortality rates as reported by THCIC. While the charges do not reflect the discounts that hospitals give to insurance companies and large employers, they do reflect the price an uninsured patient would be billed for the procedure.

“Even though most people are not paying their own bill,” says the TBGH’s Fazen, “we think it’s important that people understand what the sticker price is. Those who are uninsured will pay the sticker price. For those on Medicare, Medicare reimburses a flat rate on heart care, so it won’t make a personal difference but it raises questions.”

Compare before you buy

Thirteen acute-care hospitals today serve the Central Texas area. (See chart, “Acute Care Hospitals Serving Central Texas.”) A person with health insurance may be limited to half that number, but usually still has several options available in-network.

See sidebar story: Acute-Care Hospitals Serving Central Texas

Patients preparing for a scheduled heart surgery—as well as many other common surgical procedures and treatments—can now look at any of several major “report cards” based upon detailed government information. The reports cover the volume, mortality, and hospital charges associated with a wide range of specific procedures. Patients may be able to get information through their own health plan.

After years of delay, the THCIC began last year to publish mortality rates for selected procedures that consumers can use to compare one local hospital to another.

Using this information and survey data, the TBGH publishes information about mortality, cost, and adherence to certain best practices. Aetna, a major area health plan, allows members to create personalized reports about hospital quality on-line. And national quality report cards, like HealthGrades (www.healthgrades.com), include Texas hospital information from federal sources, primarily Medicare.

“This new public reporting is the most significant event for consumers,” says the TBGH’s Fazen. “Hospital quality has been a black box. This is the first time it’s been opened up, and it’s finally making the providers accountable. Performance improves because nobody wants to look bad.”

Many patients scheduling surgery probably don’t know about the mortality rate, cost, and hospital-performance measures currently available. Hospitals generally don’t tell consumers about the reports, and there has been very little Austin-area press coverage.

Larry Sauer, a local attorney, asked his doctor to conduct a heart scan two years ago. Several tests and preliminary procedures indicated severe blockage and he had to schedule bypass surgery. Sauer researched his hospital the only way he knew how.

“At each stage we checked with friends and other doctors,” he said. “When we knew I needed surgery, we immediately called a family friend of a friend to ask about the surgeon. We talked to a couple of other people too.”

The references reassured him that he could expect good treatment at Seton Medical Center, and he went forward with the surgery there. “I thought they were good. The doctors were great.” His sextuple bypass, open-heart surgery went well and he is completely recovered.

But he would have looked at the data on heart care if he had known about it. “If there’s a variation among the hospitals, I would have wanted to know that,” says Sauer. “I would expect my surgeon to tell me that.”

Area employers are starting to tell their employees about the report card information. “Any Dell or HEB employee can access this,” says the TBGH’s Fazen. “Right now employees are going through open enrollment and they are definitely using this information. The movement to get more information about quality to consumers is partly employer driven.”

Area employers are starting to tell their employees about the report card information. “Any Dell or HEB employee can access this,” says the TBGH’s Fazen. “Right now employees are going through open enrollment and they are definitely using this information. The movement to get more information about quality to consumers is partly employer driven.”

St. David’s Foster believes that the data is not yet good enough for consumers to use to evaluate hospitals, in part because some of the reports rely on two-year-old data.

“Am I a believer in public information of quality outcomes? Absolutely I am,” he says. “Do I think the community ought to know what kind of outcomes their hospitals are producing? Absolutely I do. Do I think it ought to be accurate and timely and have a methodology that is statistically valid? Yes, and I don’t think we’re there yet as an industry. And we need to get there.”

So you’re having a baby!

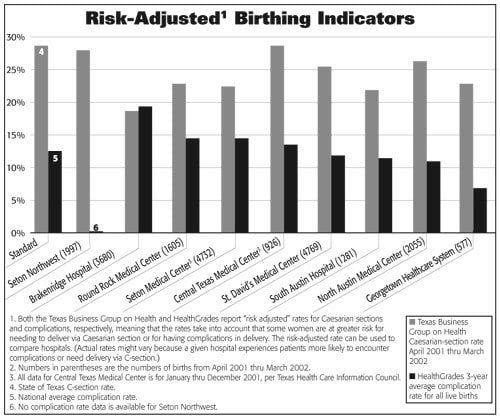

The highest volume business at most any hospital is the birthing center. Area hospitals facilitate the birth of about 20,000 new regional residents each year, largely at Brackenridge Hospital, Seton Medical Center and St. David’s Medical Center.

Because many healthy people use the hospital only when it’s time to give birth, birthing care has become a significant cost driver in health insurance. As managed-care plans looked for ways to reduce spending in the nineteen-nineties, they began to track a wide range of birthing-care data. In part because of that early interest in cutting cost, consumers today can gather a great deal of helpful information on local hospitals—including comparative prices.

All local hospitals in Austin conduct fewer Caesarian sections that the statewide average, and Brackenridge Hospital conducts relatively few compared to other area hospitals. The THCIC reports that fewer C-sections may indicate higher quality, but the TBGH is cautionary.

“There is a lot of controversy over the reduction in C-sections,” says Fazen. “Some have done studies that show that when the C-section rate gets too low, there are complications.”

Scott and Jessica Ogle of Pflugerville were shopping for a birth hospital in the spring of 1998. They toured a number of delivery facilities, and twice came back to visit Seton Northwest Hospital. They decided that it would be a good place to have their baby, which arrived via a full-term, uncomplicated April delivery.

But when their baby stopped breathing in her mother’s arms two hours after birth, the hospital didn’t respond as the parents expected. According to medical reports filed with their lawsuit in Travis County, “When the nurse called for help there was not an immediate response and she called out the door, she pushed the emergency call buttons, she called the nursing desk, and the father proceeded to the emergency room to get an emergency room physician.” An anesthesiologist arrived but put in a breathing tube that was too small, according to their lawsuit, and twenty-four minutes after the baby began to suffer, a neonatologist arrived, transferred the baby to a different nursery, and replaced the tube with a larger one. By this time, baby Lindsay Ogle was suffering from significant brain damage. The family settled with Seton last year. Lindsay Ogle died this summer.

The most significant quality-of-care issue for parents choosing among hospitals may be the hospital’s ability to handle the worst, unexpected complications of childbirth. Only four hospitals in the Austin area have a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), for example. Babies like Lindsay Ogle, born at Seton Northwest Hospital, and those born at Seton Southwest Healthcare Center, who need an NICU will be transferred to either Children’s Hospital of Austin or Seton Medical Center. Children born at South Austin Hospital or Round Rock Medical Center will be transferred to either St. David’s Medical Center or North Austin Medical Center.

Even if the hospital has a NICU, it may not be adjacent to the regular birthing areas. When the City of Austin elected to create a new city-owned hospital on the fifth floor of Seton-run Brackenridge Hospital (the Austin Women’s Hospital, to be operated by the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston), ease of access to the NICU for those mothers who elected the fifth-floor hospital was a critical issue addressed in the final contract.

According to St. David’s Foster, parents should ask about the system of transport to an NICU if the facility does not have a unit on site. “If they don’t have a neonatal ICU on site, that hospital should have a seamless and very quick transport system to get the baby to a neonatal ICU should the baby need one. And also have neonatologists available to care for the baby on an interim basis until the child can get to the neonatal ICU. That’s why the St. David’s (HealthCare) Partnership has a neonatal intensive-care transport system, which is an ambulance system solely dedicated for neonatal transport.”

Peg Moline, editor of Fit Pregnancy magazine, recommends that families select a hospital with an NICU just in case the baby needs extra help after birth. “When you take a tour, what you want to look at is how the place feels to you. We like to say, find a place that’s homey and high-tech,” she told ABC News this spring.

Complex patients and the frail elderly stress the system

Frail elderly, very sick, or complex patients with several related health problems require much more support from hospital staff than younger or healthier patients, and if the level of care slips, the results can be disastrous. For example, when a person with fragile skin or bony joints must stay in bed to recover from illness or injury, the skin can break down into open wounds, called skin ulcers or bed sores. In an elderly patient, skin breakdown can lengthen recovery and lead to serious infection and even death.

In 2001, the family of Clarence Grohman sued South Austin Hospital over wounds he allegedly developed while under the hospital’s care. According to the lawsuit filed by Grohman’s family, the bed sores he developed in the hospital contributed directly to his death a few months later. In this case, the medical reports filed with the lawsuit said that Grohman was checked for skin deterioration every shift but no evidence of a problem was noted except for nursing notes showing application of a dressing. After his transfer to the hospital’s skilled nursing unit, a physician ordered wound care, but there was no evidence that a treatment plan was implemented. By the time he returned to the nursing home, he had serious wounds, and “his loss of skin integrity directly contributed to his overall decline and death,” according to the family’s medical expert. South Austin Hospital denied liability and the lawsuit is still pending.

See sidebar story “California Implements Minimum Nurse to Patient Ratios”

Also in 2001, staff at a local nursing home sent photographs to Medicare investigators of nine such wounds on another elderly patient transferred back from South Austin Hospital, whose name was not disclosed in Medicare documents. According to the Medicare investigation, the man, who had been able to walk with a cane and had no notable skin problems, arrived at South Austin Hospital with a fracture. Although hospital staff initially assessed him as high risk for skin ulcers, no special treatment plan was created to prevent them and once they began to appear, there was no documentation that a registered nurse (RN) ever evaluated the wounds in accordance with hospital policy. By the time he returned to the nursing home, the patient had sores on his heel, low back, buttocks and shoulder.

South Austin Hospital responded to the Medicare investigation by modifying its assessment tool and improving referral to the hospital’s specialty wound nurse. According to the hospital, it has now adopted a skin and wound scoring scale that assists caregivers with assessment of risk and choice of treatment.

Many fragile elderly patients and those with several health problems end up in intensive care for part or all of their hospital stay. Therefore the quality of the intensive care unit may be the most important factor in selecting a hospital. Based on many studies of quality outcomes, a “closed” ICU run by “intensivists,” physicians who specialize in the care of complex and very sick patients, is recommended by the Leapfrog Group (www.leapfroggroup.org), a coalition of more than 140 public and private organizations that provide healthcare benefits. This closed system limits the care to a designated group of doctors and is designed to ensure that all the specialists work in a coordinated fashion.

No local hospital is organized in the way recommended by Leapfrog, but all use intensivists to coordinate care in the ICU.

“Within our organization we have intensivists at all our hospitals and they pretty much provide the bulk of all the care in our intensive care units,” said Foster of St. David’s. “It is not mandated that they are the only ones that can care for patients. Because frankly, if you have an open heart surgery patient, immediately after surgery there are surgical issues that I would want the surgeon addressing and not a medical, critical-care intensivist. At some appropriate time, there’s …a hand-off to the critical-care physician. And we do have those resources available.”

Foster believes that families of patients with very complex or critical health problems should pick the hospital with the widest range of specialists available. “I would want to be very sure that whatever hospital I admitted my family member to had a very comprehensive array of physician specialists that were on staff that would be there to care for my family member, number one, because there are multi-system issues going on with those patients. And number two, these patients probably have a higher probability of maybe having some kind of problem that would land them in the intensive care unit. And so I would want to make sure that there was a well trained group of intensivists, or critical-care specialists.”

A complex patient like Clarence Grohman requires continuous attention to detail from an often busy staff, and sometimes patients and families report better care if the hospital allows the family to bear a portion of the load.

Mirav Schloss, a severely autistic adult child with significant physical disabilities, has been in and out of hospitals all her life with a complex array of conditions. “The best hospital stay we ever had was in Round Rock Medical Center,” reports her mother, Hadassah Schloss. “I stayed there twenty-four hours a day for a week. They let me administer her meds. They were so happy that I stayed.”

Mirav Schloss, a severely autistic adult child with significant physical disabilities, has been in and out of hospitals all her life with a complex array of conditions. “The best hospital stay we ever had was in Round Rock Medical Center,” reports her mother, Hadassah Schloss. “I stayed there twenty-four hours a day for a week. They let me administer her meds. They were so happy that I stayed.”

On another occasion when Mirav was an in-patient at St. David’s Medical Center, Schloss noted the nursing staff shortages. “They don’t have enough staff,” she recalled. “I clearly remember it was the same people from early in the morning till late at night. They worked long shifts. That’s why they were so happy to have us. Mirav had to be fed and helped with the washing and everything. I got her up. I made her bed. I think it would have been a problem for them if I was not there. A lot of families around us did that too, because there was not enough nursing staff.”

Nursing shortages

Families that cannot sit bedside twenty-four hours a day must rely on staff, and staff can sometimes be stretched thin at Austin’s hospitals.

“I was in the hospital three days and two nights,” says Claudia Sperber of her appendectomy care at Seton Medical Center. “I probably saw one nurse twice. Otherwise, I never saw the same nurse twice. The nurses were very busy and they made mistakes. One messed up (inserting) an IV (intravenous device for delivering solutions, medicines and nutrients). Another gave me medication in the middle of the night and again early in the morning that was only supposed to be given on a full stomach. It made me sick and I couldn’t (check out) when I was supposed to.”

This kind of experience is unfortunately all too common, and the shortage of nurses carries dire implications.

A study of 232,342 patients, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association last year, found that patients’ risk of death increases seven percent for each additional patient under a nurse’s care. Nurse-to-patient ratios at the hospitals studied ranged from one to four to as high as one to eight for general medical-surgical units. Researchers estimated that a nationwide ratio of one to eight would result in 20,000 additional patient deaths each year.

Reducing the number of patients under a single RN also reduces the patient’s chances of getting urinary tract infections, pneumonia, shock, and other serious complications of hospitalizations, according to another study published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine. It found a two percent to nine percent increase in the rate of serious complications in hospitals with fewer RNs on staff. The number of less qualified staff (licensed vocational nurses or technicians) do not appear to affect patient outcomes.

“Patients should definitely ask their hospital how many RNs there will be on their ward,” says the TBGH’s Fazen. “Its kind of like school. You want to know that there are enough teachers for the number of students. In a hospital, you need to know not only how many are on the day shift, but the ratio for all three shifts. A hospital that is customer oriented should be ready to make this (information) available. If the hospital doesn’t, maybe you should be looking somewhere else.”

The Texas Nurses Association also encourages patients to ask about the ratio of RNs to patients but does not support a minimum ratio. “Everyone should ask,” said Executive Director Claire B. Jordan, “but there is not a set ratio that is the right delivery model for every patient.”

Currently Texas does not mandate that hospitals disclose nurse-to-patient ratios to prospective patients. The American Hospital Association collects information on nursing staff levels, but this information is only available to those willing to buy a costly database, according to Consumer Reports magazine.

According to Hayes, Seton hospitals would provide prospective patients with information about the number of nurses on the ward to which they would be admitted.

St. David’s Foster argues that patients should not try to shop for a hospital based on nursing staff ratios, and said his hospitals would not provide that information because it is not helpful.

“I don’t think a patient would want to try and shop what the patient ratios are from one hospital to the other, because they may be on one unit in a hospital with a mix of patients very different than on another unit in another hospital with a totally different mix of patients, where the staffing may be totally different. And so most hospitals staff based on acuity (the severity of the patients’ illnesses).”

The National Nurses Alliance, a project of the Service Employees International Union representing 110,000 of the nation’s nurses, disagrees.

“Of course the staffing must be based on the acuity of the patients,” said Caroline McCullough, coordinator for the Alliance. “But there’s a standard level of care that must be met at all times regardless, and then you analyze the needs of the individual patients and you increase your staffing if necessary.” The Alliance recommends that patients ask how many RNs there will be. On a normal medical-surgical unit, the Alliance states that patients should expect no more than four patients for each RN.

“It’s our responsibility as healthcare professionals to inform consumers what they can expect from their hospital care,” McCullough added. “All this secret stuff really doesn’t help get quality in hospitals in America. You can find out more about the accident rate of the car you buy than you can find out about the delivery of care in the hospital. Hospitals are resistant, and that’s why there should be a law that sets out a minimum standard that all hospitals have to meet.”

Filling the nursing gap

The American Hospital Association estimated that the nation needs 126,000 more nurses that we had in 2001. Texas ranks fifth among states with the most severe nursing shortages, according to the Texas Nurses Association.

The severe nursing shortage puts additional pressure on the nurses we do have. Seventy-two percent of nurses surveyed last year by the Regional Center for Health Workforce Studies, a research facility within the Center for Health Economics and Policy of The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, said they were exhausted, and fifty-five percent reported increased patient loads in the last two years. “I observed large patient loads per nurse,” one nurse commented, “nurses who floated to another unit without adequate preparation…low pay for hospital nurses, mandatory ‘doubles’ (double shifts), and denial of vacation requests due to patient census.”

Realization of this dire nursing situation and recent national studies linking high nurse-to-patient ratios with increased patient mortality have bumped the nursing shortage to a high priority on the nation’s legislative agenda. Lawmakers in Wisconsin, Massachusetts, Florida, and Pennsylvania proposed bills that would mandate specific minimum staffing levels. California implemented such a bill this year. (See accompanying article, “California Implements Minimum Nurse-to-Patient Ratios”) The Governor of Illinois just signed into law a bill that mandates disclosure of nurse-to-patient ratios for Illinois hospitals. Several other states are considering variations on such a law—but not Texas. US Senator Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii) introduced federal legislation this spring.

Meanwhile, the Texas Nurses Association is working with Texas hospitals to implement a number of additional measures of quality that relate directly to the adequacy of nursing staff. “We are requiring that hospitals measure indicators like falls. More patients fall if there are fewer RNs because if they hit the call button and don’t get a response (patients) are more likely to get themselves up,” said Jordan.

In 2001, Medicare investigated such a fall at Seton Medical Center. A registered nurse was not immediately available to help a patient clean up incontinence. The patient ended up on the floor and she could not get back in bed, even with assistance. She later complained of bruising when staff pulled her up and back into bed. Seton agreed to address the increased need for monitoring of such patients in the plan of care.

Since that time, both Seton and St. David’s have hired additional nurses, reduced the use of temporary nurses, and eliminated mandatory overtime that was once used to make sure the wards were staffed.

“We asked our people about staffing last week,” said Seton’s Hayes. “It was a problem two years ago. Not so right now. Five years ago we were using lots of (temporary) agency nurses. But just as important as having the number is having the right combination (of nurses) and having some continuity.”

Donna Stanley, a former Brackenridge RN now working at North Austin Medical Center, agrees that there are now more nurses than there were a few years ago. But she says the new nurses lack training, and continuous training by more experienced nurses is critical.

“You have to train the nurses. When they get out of school the training has only just begun,” she says. “Make sure the teaching is set up from people qualified to teach.” Stanley, concerned about inadequate training at Brackenridge, complained to supervisors and was eventually fired, leading to a whistleblower suit currently pending in Travis County.

“We brought younger nurses up to charge position (a supervisory role),” she told The Good Life. “But we had trouble with managers not training them and then they were fired. We wanted them trained.”

According to Hayes, Seton has significantly improved the way nurses are organized. “The new patient-care model puts nurses in teams on the floor so they have some backup for a more complex patient. Or if there’s a nurse right out of school, then they will have a more experienced nurse available.”

Massive expansions currently under construction at both Seton Medical Center and St. David’s Medical Center will require many additional nurses in the next year as new emergency room and medical units open up. But RNs are difficult to find. Recent recruiting efforts to fill the thirty-three RN slots at the Austin Women’s Hospital (on the fifth floor of Brackenridge Hospital) shows that it’s hard to find enough candidates even for that facility. An October 7 story in the Austin American-Statesman said that just ten RN applicants showed up on the first day of a two-day job fair. That facility was expected to open this month or next. Competition for nurses also stemmed from the new twenty-three bed Austin Surgical Hospital that opened in Rollingwood in September. The local demand for more nurses will go up still further with another new hospital scheduled to open in August 2004. The multispeciality hospital will be located in the Westlake Medical Center, with twenty-three overnight beds, plus some twenty-five post-operative overnight recovery beds, said Rip Miller, principal and general partner.

St. David’s hospitals have worked to recruit nurses from a variety of sources to cover the expansions. “We’ve got international recruitment we’ve done in the Philippines and England and all sorts of multifaceted ways we are trying to grow the nursing program. As I’ve told people, if the nurses aren’t there we won’t open the beds,” Foster said.

The use of foreign nurses depresses wages. A registered nurse working in a Texas hospital makes an average of $45,780 a year and frequently works a second job to make ends meet, according to Jordan of the Texas Nurses Association. “Nurses through the nineteen-nineties had flat wage levels, and going out of the country helps keep those wages down.”

And the use of foreign nurse recruitment is only a short-term solution. “Nurses coming in from foreign countries stay four to six years max,” says Jordan. “They want to go home eventually. The nurse that is educated in the area tends to have a higher probability of staying in the area.”

Both the Seton and St. David’s systems are supporting significant efforts to increase the number of nurses and other healthcare workers that are educated in Austin and will work in Austin, according to both Hayes and Foster. “There are 3,000 more qualified nursing applicants to nursing schools than there are slots available across the state of Texas. And it’s principally because the faculty is not there,” said Foster.

“We have formed a partnership with ACC (Austin Community College) to create a series of grants that have enabled them to expand the faculty, and therefore expand the capacity to take on new students,” he said.

According to Foster, these efforts have already opened up forty to fifty new nurse-training slots this year at ACC. The hospitals hope to train an additional sixty nontraditional students using an on-line curriculum next year.

“In addition to that, we have been working with the Health Industry Steering Committee (an area-wide workforce planning group that includes both major hospital systems) to solicit and expose people at a younger age to the clinical and health professions that are available to them.”

High school students will start to understand their options in the health professions better after participating in the new Health Science Institute at Lanier High School.

“AISD (Austin Independent School District) and ACC developed a curriculum that has enabled people who elect to enter the (Institute) to take ACC credit courses,” said Neal Kocurek, CEO of St. David’s Health Care System. “And if they maintain a certain grade level in this health (Institute) program, then they can enter the ACC nursing program straight out of high school.”

This could help relieve the long-range need for nurses, Kocurek said. “The average age of people entering the ACC program has been twenty-nine. They go back to school from another career or they just wait a long time to make that decision to go into nursing. We will be moving eighteen or nineteen year olds into the field. The average age of a nurse is forty-four, and if you don’t start until twenty-nine it shortens the career. This will help put people into the program much earlier.”

Jordan of the Texas Nursing Association notes that even in conditions of severe nursing shortage, some hospitals manage to be fully staffed. “The American Nurses Association studied why some hospitals have no shortage while others do, and they built a set of standards based on the characteristics of the no-shortage hospitals.”

The nursing staff standard promoted by the American Nurses Credentialing Center, a subsidiary of the American Nurses Association, is called the Magnet Award. “There are eighty-eight hospitals or hospital systems that have met those standards,” said Jordan. “The Seton system here is one of those hospitals. Magnet status should ensure you a higher level of care.”

Seton Medical Center, Brackenridge Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Austin, and Seton Northwest Hospital—all operated by Seton Healthcare Network—were awarded Magnet designation in December 2002. Although studies comparing patient outcomes at Magnet hospitals attribute improvements to higher nurse-to-patient ratios, Magnet hospitals are not required to meet minimum staffing levels. According to JCAHO, patients in Magnet hospitals spend less time in ICU, “perhaps reflecting a lower frequency of adverse patient events and earlier nursing interventions for incipient problems.”

“One of the things we’re blessed by,” said Seton’s Hayes, “is a recognition that in a community that has grown forty percent in the nineteen-nineties, we need everybody on the team to provide healthcare. So the majority of the time St. David’s and Seton look for ways that we can work together, and we’ve done that not just in (Health Industry Steering Committee) but in the indigent care collaborative and in planning after 9-11. (In) most communities, the hospitals don’t cooperate.”

Medical error

When thirty-eight-year-old Tammie Abrego scheduled her hernia operation at Seton Medical Center in 2001, she didn’t expect to end up back in the hospital again quite so soon. But when she woke up in the recovery room she realized that her surgical scar was on the wrong side.

See sidebar story “To Pick the Best Hospital Use Your Right to Know”

Her doctor had operated on the right rather than the left side, even though her medical order clearly indicated where the surgery was to occur, according to a physician who reviewed her medical files for her lawsuit. She had an unnecessary operation, and had to go back for the original surgery. Angry, she charged the hospital with assault in a civil suit. Seton settled her lawsuit and she signed a confidentiality agreement preventing her from talking about her case.

Between 44,000 and 98,000 patients die every year from medical errors, according to the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences, a nonprofit organization that provides independent guidance on matters of science and medicine. Mistakes in surgery or misdiagnosis can result in death in the worst cases, and frequently require repair by additional surgery or an extended hospital stay. Yet hospitals do not publicly report information about their rates of medical error and consumers cannot find out if one or another area hospital is more prone to mistakes.

The hospitals’ national accreditation agency, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), has called on hospitals to voluntarily report very serious medical errors that result in death or serious injury, but reporting levels are low and the information held by JCAHO remains confidential. The voluntary guidelines call for the hospital, as part of its quality of care system, to perform an analysis of the root cause of the death or serious injury and submit the analysis to the JCAHO. The JCAHO said it would not release information contained in the analysis, but would confirm whether it considered the analysis to be “thorough and credible.”

To relieve serious lower back and leg pain in 1998, Betty Jean Valerga underwent spinal surgery at St. David’s Medical Center. Six weeks later, she appeared to be healing and felt well enough to return to work. But in October 2000 she began to experience severe pain again in the same region. Her family doctor ordered an emergency x-ray, and identified a five-centimeter (two-inch) object at the surgery site. “On the x-ray it looked like a metal rod in the surgical area,” Valerga recalls. “My primary care physician sent me home to bed immediately.”

Valerga said when she called her surgeon’s office, the nurse told her that it “could not be our problem; we never leave anything inside after surgery.” The next physician she consulted told her surgery would be required to remove the object—which eventually turned out to be a surgical marker (a thread originally attached to a sponge) from the first operation. She filed suit. St. David’s denied any culpability, but also responded by suing Johnson & Johnson, the maker of the product.

“It would have made me feel better if someone had simply said, ‘We screwed up,'” says Valerga. “But to say, ‘We didn’t do anything wrong,’ it was like I made the whole thing up. I know people are lawsuit happy, and there are many things that are beyond a doctor’s control. But not to be held accountable, that’s not right either.”

According to Foster, St. David’s HealthCare Partnership hospitals routinely draw the surgical site on the patient to avoid operating on the wrong part of the anatomy. Seton conducts what Pat Hayes calls “patient safety rounds” to regularly investigate processes of care and look for ways to improve.

Medication errors

Medication mistakes are among the more common patient-care errors. According to the Leapfrog Group, more than a million serious medication errors occur every year in US hospitals, including administration of the wrong drug, drug overdoses, and overlooked drug interactions and allergies. The Institute of Medicine estimates that medication errors cost 7,000 people their lives every year and add $2 billion to our nation’s healthcare bill.

Studies show that certain best practices by hospitals can substantially reduce medication errors—at least in certain units—but no hospital in the Austin area has yet implemented these recommended practices, according to the TBGH report cards.

When Charles Ly dropped to the sidewalk outside a local restaurant in 1999, he was rushed by ambulance to Seton Medical Center. At Seton, an emergency room physician misread a computed tomography scan and misdiagnosed bleeding in the brain as calcification, according to the family’s medical reports filed in court. The physician prescribed a drug with a higher risk of complication for patients with hemorrhage. Ly’s condition worsened, and his family ultimately sued Seton over the care he received. Ly survived but needed significant rehabilitation, and the family’s lawsuit is ongoing. Seton has denied any negligence in the case.

Federal Health and Human Services investigators substantiated a medication error at Brackenridge Hospital last year. An emergency room doctor prescribed a sulfa drug to a patient with sulfa-drug allergies, even though the allergy was clearly recorded in the emergency room record. According to the hospital’s response to Medicare, information about the allergy was not transcribed from one set of forms to another, to be available to those who were to administer the drug in question. In fact, the form seen by the treating nurse erroneously claimed that the patient had no allergies.

According to the Leapfrog Group, this is exactly the kind of medical mistake that can be readily avoided by computerizing the prescription process. Computerization allows hospitals to intercept errors when they most commonly occur—at the time medications are first ordered. The doctor enters the order directly into a computer, which checks the order against other patient information including lab reports and other prescription information. The system automatically warns against drug interaction, allergies, and overdose.

Neither St. David’s system hospitals nor Seton system hospitals have a computerized physician prescription system in place. St. David’s expects to initiate such a system. St. David’s Foster said, “We’ve installed the necessary prerequisite software pieces to get there, but before that we’re going to be installing the Electronic Medication Administration records, the bar-coding system for medication administration, and that will be coming on line next year. It’s the concept of bar-coding all drugs, bar-coding all patients with their armbands, and the nurse wanding the drug, wanding the patient armband, and if there’s not a match she doesn’t give the drug. It takes any human error out of the process.”

Seton is investigating such a bar-code system, Hayes said.

St. David’s HealthCare Partnership’s four hospitals started the effort to eliminate human medication error by computerizing medication delivery within the hospital pharmacy.

“We’ve already done some things that no other hospital in the community has done,” says Foster. “We have a robotic system within our pharmacy that has a 99.999 accuracy rate in pulling drugs out of inventory. When humans are doing it there’s the possibility of human error, grabbing the wrong drug or the wrong dose, but we’ve automated that function to promote 100 percent accuracy, since it’s a robot that, based on orders entered into the system, pulls the drug and dispenses it to the dispensing cart and ensures that it’s accurate. So that, coupled with what we’re doing on the nursing side for the Electronic Medication Administration system next year, ought to make that pretty much foolproof. Once you layer on top of that the physician’s computerized order-entry of the medication you’ve closed out the entire loop. That’s pretty significant because…this technology takes that to a whole new dimension, a whole new threshold.”

St. David’s will install the new medication information systems in stages next year starting with North Austin Medical Center, then St. David’s Medical Center downtown, then Round Rock, and finally South Austin Hospital. “We’re talking about a multi-million-dollar investment in the technology to be able to do that,” Foster said. “A lot of hospitals can’t afford that. I think we will be the first in Austin and in this area.”

Hospital acquired infection

Nancy Trease has spent a lot of time in the hospital with recurring bouts of cancer, and her medical needs are complex. But her stay at Seton Medical Center got a lot longer last year when she came down with a drug-resistant, staphylococcus (bacterial) infection that invaded her chest and added a month to her hospital stay.

“No one discussed this possibility with me,” she says. “I ended up with severe, septic cellulitis. I had to be in traction because they couldn’t repair a break in the left hip until they got the infection under control.” Trease remembers little about that time, due to the fever and pain. “I was on morphine constantly,” she says now.

See sidebar story “Some Medical Procedures Rarely Done in Austin”

But a friend who stayed by her side during that terrible month attempted to improve the care she was receiving. Trease said, “Randy wrote a letter to the hospital about the infection. He was identifying things that were not satisfactory. Every time something wasn’t right, Randy would raise Cain and it would get better. The orthopedist really objected to Randy advocating for me. He said, ‘How could Randy know I had gotten that infection from the hospital.'” Trease is convinced her infection was a result of the care she received in the hospital, but was grateful for surviving her ordeal and let the matter drop.

Patients like Trease can get infections in the hospital because hospitals are indeed a favorable breeding environment for a wide variety of germs. At the greatest risk are surgical patients, those in the intensive care unit, and those using invasive technologies like catheters, ventilators, and IV lines that can carry germs into the body.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 88,000 people each year die from infections they contract while they are hospitalized for other health problems, making this the sixth-leading cause of death in the United States. “I’ve been living with cancer for many years,” says Trease, “but that infection just about took my life.”

Years ago, in an effort to help hospitals develop better ways to prevent the spread of infection, the CDC set up a national, voluntary infection-reporting system. Although more than 300 hospitals nationwide now participate in this system, no local hospitals participate. According to St. David’s, most of the participating hospitals are teaching hospitals or academic centers. Hospitals participating in the CDC system reduced infection rates over the last decade, but there is little public information available about infection-control improvements for most hospitals in the country, including Central Texas hospitals.

“Unfortunately, there is no good reporting,” says the TBGH’s Fazen. “A hospital infection is a ‘never’ event—something that should never happen. But right now it’s nearly impossible for a consumer to get information about hospital infections.”

Local hospital officials concede that they do not publicly report infection-rate information and consumers cannot readily find out whether a hospital has an infection problem. “You might not know. That’s a very valid issue,” said St. David’s Foster. “There’s a blue ribbon, gold standard (method) of how you address that relative to antibiotic therapy prior to surgery, and of course we require that all of our patients receive that. And that pretty much addresses your surgical infection rates. Across the country, surgical infection rates are very low. Now there may be other infections that occur out there for other reasons.”

According to Foster, all hospitals track infection rates internally. “All hospitals would be tracking their infection rates and have a process for reviewing that. We have infection-control nurses and infection-control policies and procedures in our hospitals and that’s something the Joint Commission (on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) reviews you on. All hospitals do that.”

Seton also tracks its infections internally and does not disclose that information.

According to the CDC, diligent handwashing is among the most important procedures that actually prevent the spread of infection among hospital patients. This basic precaution may be one of the most difficult things to enforce in a large hospital with a busy staff, and handwashing procedures have to encompass all the staff who move from room to room.

Both Heart Hospital and South Austin Hospital have been investigated by Medicare and found deficient in certain infection-control practices-particularly with respect to food service and housekeeping staff.

Medicare found problems with Heart Hospital in 1999 related to staff working in both food service and in housekeeping, with potential cross-contamination. Heart Hospital—which declined to be interviewed for any aspect of this story—addressed the problem by promising to monitor infections and communicable disease, and giving disposable gowns to dietary employees, according to the Medicare report. Medicare has not identified problems at Heart Hospital since then.

In 2002, Medicare found that South Austin Hospital dietary employees moved from room to room—including rooms where patients were at higher risk of infection—without washing hands. Visits in both January and February 2002 found continuing deficiencies in handwashing. According to Medicare, “The facility continued to fail to insure a consistent infection-control program as it specifically related to the delivery of patient trays and handwashing.”

Medicare investigators found that staff delivering food trays at South Austin Hospital did not remove gloves or wash hands between rooms, nor did they ensure that the right tray went to the right patient by checking the patient’s wrist band or calling the patient by name. In response to the investigation, South Austin Hospital promised to have the dietary director observe tray delivery and monitor compliance with infection-control processes daily.

“Our infection-control procedures and process call for washing hands in between seeing patients,” said Foster of St. David’s Partnership, which operates South Austin Hospital. “Now, is there a possibility that there is someone who doesn’t wash their hands? Obviously, you wouldn’t believe me if I said that it doesn’t happen. Now someone who doesn’t wash hands as an oversight or something doesn’t automatically create an infection. But it isn’t following our own internal processes. We take those very seriously. There is a process. There are policies. They are monitored. If an employee forgets one time or something, that may happen but it’s not very often. It’s drilled into their heads.”

But there are also technical solutions. Many busy hospital staffers do not wash enough because they don’t feel they have the time to stop and scrub between every patient contact—even though they know how important it is. Many hospitals use an alcohol-based alternative to soap that kills germs with less time spent scrubbing.

“We certainly are using (alcohol-based washes) more,” said Seton’s Hayes. “Its very, very effective and convenient. I don’t know the extent of our current use, but I’m guessing it will ramp up. Now that isn’t going to happen in surgery, but when you are going out of patient rooms time after time after time, that’s where that is really helpful.”

According to the CDC, the extra days people have to stay in the hospital due to a hospital-acquired infection add $5 billion to the nation’s healthcare costs. A study released last month in the Journal of the American Medical Association noted that the additional cost associated with an average infection due to medical care was $40,323. According to the hospitals, they bear the bulk of that extra cost themselves.

“Most insurance plans pay a lump sum amount for the diagnosis that is cared for in the hospital, regardless of whether the patient stays three days or 300 days,” said St. David’s Foster. “So because of that, typically speaking for the vast majority of our patients, that is how payment is rendered. So the hospital would end up absorbing the incremental cost beyond what is expected.”

Uninsured patients, of course, do not negotiate diagnosis-based, lump-sum bills. According to St. David’s, those patients don’t pay anything, whether or not they get a hospital infection. “They don’t pay anything. The truth is in 2003 we’ll render close to $100 million in free care for the people of Central Texas, largely those that are uninsured and can’t afford to pay.”

Many groups advise consumers to remain vigilant on handwashing and other safety issues. “People should ask their nurses and other caregivers if they have washed their hands,” the TBGH’s Fazen advises, even if the question seems awkward.

Clarian Health, an Indiana-based hospital system, advises patients to “be a handwashing warden” by asking all hospital personnel who enter the room to wash their hands in your presence. Clarian further advises its patients to ask personnel who wear fake nails to put on gloves before touching them, because studies show that harmful bacteria collect under these nails even after washing.

Tony Field, a British financial advisor who turned patient advocate after suffering a serious hospital infection, advises patients to carefully examine their room for dust and get someone in there to clean it if needed.

Our local hospitals advise that patients take an active role in all their care. “If a patient (or) a family member feels concerned about the level of attention to a particular thing…they should very much bring that to the staff’s attention and voice their concerns,” says St. David’s Foster. “I don’t think anyone should sit idly by. If something doesn’t seem right to them, they should say so.”

Emergency room care

Because emergency rooms have to take all comers, regardless of ability to pay, and have to address every kind of illness for all ages and types of people, the emergency room has become the nation’s front line against disease. The pressures on emergency rooms are fierce—too many patients and sometimes too few doctors and nurses to diagnose and treat them. At the same time, patients with serious illnesses don’t expect long waits for emergency treatment, multiple transfers in search of the right specialist, or medical errors.

Austinite Pam Uhr, mother of three very active boys, has visited local emergency rooms many times over the years. “I have several ER experiences with my kids at Children’s Hospital and Seton, and visits for myself and my mother-in-law at North Austin (Medical Center).” Most of those experiences have been good, she says, and some hospitals appear to have systems in place to smooth the bumpy ride.

“Seton has what they call a ‘minor emergency track’ that diverts some of the patients,” Uhr said. “That way you get to see a doctor quickly. At Children’s all the kids are together. You are divided by only a curtain. One time, on the other side was a kid who was very, very ill. It makes you wonder about infection. The ‘minor’ ER lets them separate the really sick ones from the ones who still need to be seen but are not so sick.”

“Seton has what they call a ‘minor emergency track’ that diverts some of the patients,” Uhr said. “That way you get to see a doctor quickly. At Children’s all the kids are together. You are divided by only a curtain. One time, on the other side was a kid who was very, very ill. It makes you wonder about infection. The ‘minor’ ER lets them separate the really sick ones from the ones who still need to be seen but are not so sick.”

According to Foster, all St. David’s HealthCare Partnership hospitals now have such a “fast track” system. “We have a fast-track triage at all of our hospitals now for patients with less urgent needs. We call it Quick-Care. To try to expedite care, we also have bedside registration, meaning the paperwork gets done at bedside after the triage and basic treatment begins.”

“My wife broke her arm,” said Neal Kocurek, CEO of St. David’s Health Care System. “Immediately she was taken into a treatment room. She was treated, then the administrative person brought the computer on the rolling cart to do the registration.”

Waiting can be more than just an inconvenience. When Pam Uhr’s mother-in-law was very ill with pancreatic cancer, she called Uhr one day in terrible pain. “I called the doctor and he said to take her to the ER. We waited in the waiting room at Seton Northwest Hospital for hours. It was horrible. It was crowded. Packed full of people. She was barely able to sit up. She would rather have suffered at home than in that waiting room. Once she was admitted, it was really great. The doctor was so good we had to call and thank him. As soon as he came in he ordered pain meds and got her stabilized. But it was a long wait.”

Sometimes patients wait hours in the ER for an on-call specialist needed to review the case. A South Austin resident went to South Austin Hospital emergency room this past spring after a serious bicycle accident left him with deep skin damage, a twisted ankle, and shoulder pain. “It was 8am on a Saturday,” he remembers. “After we got there, it took an hour to do the paperwork, then I sat on a cot for an hour. A doctor came in and cut open the elbow area and pulled the stones out. Then I sat there for hours, holding my arm up. The doctor said he needed an orthopedic surgeon and they didn’t have one. I waited for hours. The guy never came.” The patient finally left the hospital about 7pm, without a consultation from a surgeon and with instructions to see his own doctor on Monday. When his doctor referred him to a specialist, the broken clavicle was finally diagnosed. “It’s not really fixed,” he says now with chagrin. “I can’t swim laps at Barton Springs anymore, and the ER cost a lot of money.” The patient, who spoke on condition of anonymity, is still negotiating a payment plan with the hospital over thousands of dollars in billings that resulted from this incident.

Brackenridge hospital was cited by Medicare in August and November 2002 after an on-call neurosurgeon twice refused to come to the ER to see emergency patients, according to Medicare inspection reports. In both cases, a patient arrived at the ER with persistent headache and a computed tomography scan that indicated bleeding in the brain. The neurosurgeon told the emergency room physician that she would not come in because “she did not provide care for aneurysms,” and she “accepted consultation for pediatric and personal patients only.” One of these two patients had been transferred once already from another hospital that was unable to provide adequate care.

Seton, which manages Brackenridge Hospital, refused to say whether this neurosurgeon was disciplined, citing the privileged status of the hospital’s peer-review process.

Access to neurosurgeons became a very serious problem for local hospitals last year after “a majority of the neurologists” resigned from the Seton medical staff, according to Seton’s response to Medicare investigations. This left Seton hospitals without enough such specialists to have full seven-day-a-week, on-call access for ER care.

According to Seton’s Hayes, the real problem isn’t physicians who don’t come to the ER, but the shortage of specialists in the community. “The community has a huge problem having enough specialists. That’s a big cutting-edge problem,” she told The Good Life. “Having said that, no, there’s not a problem with physicians on call, particularly at Brackenridge, where we pay for call.” Brackenridge Hospital pays specialists to be on call at the trauma center in accordance with trauma center certification requirements of the American College of Surgeons.

“There aren’t enough,” Hayes added. “Our community is facing an issue where we’re not going to have (enough specialists in)…neurology is an example. But we just don’t have anybody signed up.” According to a written follow-up statement from Seton, the system continues to struggle with specialist access because some specialists do not work with hospitals at all, but only out of a private office, while others are not willing to take emergency room calls due to practice patterns and lifestyle choices.

Medicare investigated this situation at the Seton system after a September 2002 car accident. The victim, with evidence of a brain hemorrhage, originally arrived at the Seton Northwest Hospital emergency room but had to be transferred twice before getting to a St. David’s HealthCare Partnership hospital that had neurologists and neurosurgeons available on call.

In the fall of 2002, Seton administrators met with their counterparts at St. David’s and Travis County EMS to develop a transfer protocol to ensure that patients needing neurological care would go to Brackenridge and St. David’s hospitals. St. David’s reports that its hospitals have now recovered from the neurology shortage.

“We’ve been able to recruit additional neurosurgeons,” Foster said. “We’ve recruited additional neurosurgeons to the team at North Austin Medical Center and at St. David’s Medical Center, so we have coverage across the entire partnership for neurosurgery emergency department calls. There was a period of time there when there was some spotty coverage, and what the ambulance services would do is do the best they could with that information, and route people to the hospitals where they knew they had neurosurgical coverage, but St. David’s System hospitals are now covered twenty-four/seven.”

Some of the pressure to transfer patients among emergency rooms has also been relieved by the hospital’s major expansion programs. Last year, the Austin American-Statesman reported that patients were increasingly transferred among emergency departments because the emergency rooms were too full to accept more patients. But according to St. David’s Foster, local emergency room capacity has significantly increased in recent months. “Our capital improvements have tripled ER capacity in Round Rock (Medical Center), doubled at St. David’s Medical Center and doubled at South Austin Hospital,” he says.

Keep lines of communication open

Satisfied patients interviewed by The Good Life tended to focus on the positive and respectful communication they enjoyed, while unhappy patients identified those moments when the communication broke down. Often patients enjoy very different experiences of the same hospital.

When Lynne LaFontaine of North Austin checked in to Seton Medical Center for surgery, she felt she participated fully in her care at every stage and came away very satisfied. “My doctor did a good job of explaining to me what to expect, what it would be like, how to prepare, and it wasn’t as bad as I thought it might be,” she told The Good Life. “She asked what I wanted for a sedative. She talked about everything and was open to questions.”

And it wasn’t just the physician staff. LaFontaine found that nurses also communicated openly and took extra time. “The nursing staff did a good job putting in the IV. They told me what to expect and what everything was. They made Scott, my boyfriend, feel welcome and comfortable there. I didn’t have to call them because they checked on me pretty regularly.”

David Dominguez of East Austin, recently under the knife for a hernia, likes St. David’s Medical Center because they always take the time to be informative and caring. “I’ve been in Austin all my life. I’ve had experience with other hospitals. I always get treated at St. David’s if I have the choice, because I always get treated right there. They were very clear about the instructions after my surgery, and they answered all my questions.”

Patients or the family members of patients with complex medical needs can be particularly insistent that the hospital staff pay attention to them, and even take direction. While the staff may be seeing this person for the first time, family members have years of relevant experience and knowledge.

Hadassah Schloss has taken her daughter Mirav to several local hospitals over the years. As a severely autistic adult child with significant physical disabilities, Mirav presents a challenge to any hospital system set up primarily to address physical illness. So her mother expects to be very involved in her care—and have her wishes respected.

“The worst experience we ever had was at North Austin Medical Center,” she says. “Her doctor wanted to see how her kidneys were doing and scheduled tests. We had three meetings to arrange the times for each step.”

See sidebar story “Making the Best of Your Hospital Stay”

But after carefully orchestrating the event, communication broke down. “We got to the room, and the time comes for the sedative, and they arrive with orange juice. We said no, but the nurse said it would be okay. Well it was not okay, and they couldn’t sedate her. It took seven people to catheterize her. They tried to make us (family members) leave the room. She was supposed to have the test at 8:30am. By 1:45pm she still hadn’t had the test and she was (acting) crazy. They took her back to her room and I said she needed to go home…now! But the doctor—it was like talking to a wall. I finally said I want her out, and I filed a complaint. They said they were going to talk to people, but they never got back to me.”

For the Schlosses, this incident illustrates why doctors and nurses should listen to patients and their families—even about something as simple as a glass of orange juice—and why patients and families should take extra care to ask questions and make sure that caregivers follow the treatment plan at every step.

“Make them listen and don’t let them dismiss you,” advises Schloss. “There is an attitude in the medical community that they know better. They tend to dismiss parents particularly, because parents are ‘too involved, too emotional.’ There’s a huge, huge hump you have to get over. I have to swallow lumps. But then I say, ‘Do I have to bring out Mommy Dearest? If I do, I will.”‘

Fazen of the TBGH agrees that families and patients should actively monitor the care and advocate for their own needs. “Family members need to be the advocate for the patient,” she says. “You should be given aspirin for heart care before (surgery) and when you leave. Did the doctor prescribe beta-blockers? You just can’t go into a hospital blind anymore.”

Jordan of the Texas Nurses Association recommends that patients “take a buddy. You are not at your best in the hospital, and it’s important to have someone who is fully functioning to watch out for you. And the more a patient knows about their care, the more they can be a participant. Never think that your doctor is taking care of something. If you don’t know, bring it to a nurse. The nurse is the one caring for you continuously.”

Hospitals are community safety nets

Central Texas residents depend on local hospitals for crucial medical care. Hospitals bear tremendous responsibilities. What they do—or in some cases fail to do—often makes a difference not only in our quality of life but whether we have a life left to live.

What we’ve learned in exploring how well the crucial responsibilities of local hospitals are being carried out is that patients stand a better chance if they can pick the best hospital for a given procedure, but there is not enough information publicly available. Patients and their families and loved ones need to study the charts provided with this story, do additional research, and make informed decisions when deciding what hospital to use.

Further, once in a hospital, patients, with the assistance of families and loved ones, must take an active interest in monitoring how well they are served and be prepared to intervene on those occasions, rare though they may be, when treatment goes awry. It’s a matter of life and death. And whose life is it anyway?

Kathy Mitchell, like most people, is trying to stay healthy and hoping she doesn’t ever wind up in a hospital. But after preparing this report, she will be much more savvy about picking a hospital if she does need one. This article was originally published in the November 2003 edition of The Good Life magazine.

High-Tech Hospitals

All hospitals in the Central Texas area have invested in technology, with more investments to come, and focused on improving quality in specialized areas of care. The investments and reorganizations give prospective patients a sense of the hospital’s priorities.

Neurology—Both St. David’s and Seton have reorganized neurology and neurosurgery into comprehensive care units. The St David’s Institute for Neurology and Neurosurgery at St. David’s Medical Center “is where we have our rehab programs, our rehab hospital, where we have our outpatient therapy clinics, our neurosurgery program, our neurology program, (and) our neurology ICU (Intensive Care Unit),” says Jon Foster, president and CEO of St. David’s HealthCare Partnership (a partnership between the not-for-profit St. David’s HealthCare System and Hospital Corporation of America). “It’s where we have aggregated all those neuroscience procedures and services into a robust program that is doing a fantastic job and continues to improve year over year. And that’s because it has received so much concentrated attention.” Seton has similarly aggregated such services at Brackenridge, in coordination with the trauma facilities there. In August 2002, Seton opened the new Brain and Spine Center, a continuum of care primarily focused at Brackenridge Hospital, a result of several years of work by Seton staff to put together a neuroscience center that aspires to be second to none.

Pain management—A hospital’s ability to safely, promptly and effectively manage pain can be the deciding factor separating a good hospital experience from a bad one. St. David’s had focused on improving pain management, and has been identified by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) as a top hospital. “Our pain management process within the St. David’s system have been cited by the Joint Commission as a best practice in the nation for how we monitor and deal with pain management issues for our patients,” says Foster. “That is one area we feel we’ve made great progress. It’s a much more robust system of getting feedback from patients by ranking their pain in layman’s terms, so we can really get at the heart of how they are doing and be responsive to their pain needs.”

Devices—Some procedures can only be provided if a hospital has the right tools. St. David’s system hospitals can provide digital mammography services, and expect that this new mammography tool will increase early detection of breast cancer by twenty percent. A gamma knife allows patients to substitute a noninvasive technique for cranial surgery, but the device is currently not available in Austin. St. David’s recently purchased one and is in the process of installing it and implementing a program. Last month, Seton Medical Center announced a new Nuclear Medicine System that will help physicians diagnose how well a heart is functioning, and will help pinpoint the location of cancerous tumors, bone fractures, and ruptured abdominal blood vessels.

Somebody may be watching—And this time you might be glad about it. Not yet, but in the future, patients in St. David’s intensive care units might be placed under camera surveillance. “As an additional layer of care, we would have all of our cardiac and physiological monitoring systems wired into a central station where…intensivist physicians would monitor the vital signs twenty-four hours, seven days a week, 365 days a year of every ICU patient. And in addition to that, we would have cameras of such a sophistication loaded into our ICUs that could literally do retina scans of patients, they are so powerful,” says Foster. “There aren’t enough intensivists to be in every patient’s room, so this system would leverage the ability of the physician. I think it will be the standard of care in about five years, and we’re looking at it right now for maybe implementation sometime next year.”

Model medical-surgical units—With support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the fourth-floor medical-surgical unit at Seton Northwest Hospital will pilot new health-delivery systems from October 2003 through March 2004. The program, called Transforming Care at the Bedside, was open to all nursing Magnet hospitals, but Robert Wood Johnson chose only Seton in Austin, Shadyside Hospital in Pittsburgh and Roseville Hospital in Sacramento. A national team of experts will work at each of these three sites to test new ideas for improving care, and expect to end up with proposals for better delivery of care on hospital general medical-surgical units by next year.

Some Medical Procedures Rarely Done in Austin

The Texas Health Care Information Council reports on the total number of selected procedures conducted by local hospitals each year. For each of these procedures, a higher volume is usually associated with better care. But for the following procedures, Austin hospitals conduct relatively few compared to hospitals in Dallas and Houston.

Pediatric heart surgery—Children’s Hospital at Brackenridge conducted seventy-five of these in 2001, while all other area hospitals did fewer than five such operations. By contrast, Children’s Medical Center Dallas conducted 382, and Texas Children’s Hospital Houston conducted 442.

Esophageal resection—Only The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center conducts more than ten of these procedures each year. No Austin hospital conducted more than five. Esophageal resection is a complex cancer surgery for cancer of the esophagus. Studies have shown that providers with higher volumes have lower mortality rates.

Pancreatic resection—No area hospital conducted more than five procedures. M.D. Anderson conducted sixty-six. Pancreatic resection is a complex pancreatic cancer surgery for which studies have also shown that providers with higher volumes have lower mortality rates.