About 9,800 words

The health of Barton Springs salamander is in serious decline and the federal agencies most responsible for doing something about it are once again being accused of knuckling under to political pressure, instead of relying upon scientific evidence to identify causes and cures. The point man for the US Fish and Wildlife Service who was leading the charge to protect the salamander has been transferred out of Austin. His former regional director has been reassigned. And a watered down biological opinion has been issued, killing the proposed federal protective measures that were to be applied for development projects outside the reach of Austin’s Save Our Springs Ordinance.

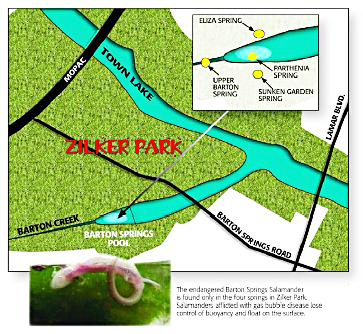

But it’s not just the salamander’s survival that’s at stake. The salamander’s habitat is the water that gushes out of four hydrologically connected springs in Zilker Park, collectively known as Barton Springs, including the ancient swimming hole that some environmental groups call the Soul of the City. The water flows from the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer. The Barton Springs segment is about twenty miles long, with a recharge zone that covers an area of about ninety square miles. The upstream contributing zone, which contains streams that flow onto and discharge into the aquifer, covers more than two hundred sixty square miles. If the water quality in the Barton Springs segment is harmful to the aquatic creatures that have lived in the springs for perhaps millions of years, then it is inching toward being unsafe for humans as well.

So the stakes are a lot higher than whether the old swimming hole is dirty, or whether the slimy little salamander that most people will never see, except in a photograph, is comfy and cozy.

Those things are indeed important, but what’s more important is that the salamander is an early warning indicator of the health of the aquifer which, according to the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, is the sole source of drinking water for an estimated 50,000 people.

If politics are undermining protection for the salamander and the aquifer, it wouldn’t be the first time that politics has called the shots. The salamander is listed as endangered as a direct result of two federal lawsuits filed by the Save Our Springs Alliance against Bruce Babbitt, then secretary of the interior. Babbitt had resisted the listing and did not do so until ordered by Senior US District Judge Lucius D. Bunton III on March 25, 1997. Bunton ruled that “strong political pressure” had played a part in Babbitt’s actions.

Part of that political pressure was a letter from then Texas Governor George W. Bush. The letter was referred to in Bunton’s decision: “The court finds that the Governor of Texas letter dated February 14, 1995, in which he expressed ‘deep concerns because the proposed action by the federal government may have the potential to impact the use of private property’ is not an appropriate justification….” (Bush was elected governor in November 1994 and took office January 17, 1995.)

Bunton found that Babbitt had acted “arbitrarily and capriciously” when he had considered political factors in making the decision not to list the salamander. Bunton’s ruling concluded that the Endangered Species Act requires the secretary to disregard politics and to make listing decisions based solely on the best scientific and commercial data available.

As a result of Bunton’s ruling, the Barton Springs Salamander was listed April 30, 1997, entitling it to federal protection under the Endangered Species Act.

Now, more than five years after the listing, there is new cause for concern. Between January 28 and May 14, 2002, eighteen Barton Springs salamanders have been found with external bubbles under their skin. A dozen of these were either found dead or died shortly after they were found. Tests revealed that the water was supersaturated with dissolved gases, mainly nitrogen and oxygen, which are the principle components of air. Gas bubble disease is a noninfectous and is similar to human decompression sickness, which is caused by rapid ascent from a higher atmospheric pressure to a lower pressure. City biologists studying the situation have developed temporary skin rashes on two occasions from exposure to the waters of Upper Barton Springs, where all but two of the diseased salamanders were found. Still, despite exhaustive efforts by the City of Austin and other agencies, the cause of the gas bubble disease remains unsolved. The only good news is that health authorities who reviewed available data in early March found no evidence of any public health risk in Barton Springs Pool or Upper Barton Springs.

Still, it’s not necessarily safe to swim in Barton Springs Pool at certain times. The pool routinely closes for cleaning once a week and is also shuttered in the event of a flash flood warning or an actual flood event, says Tom Nelson, the city’s aquatics supervisor. Scientists who study water quality in the pool are finding evidence that toxic chemicals linger in the pool for considerable periods after a rainfall even when there isn’t enough rain to cause a flood.

Barbara Mahler is a research hydrologist with the US Geological Survey [which, like the Fish and Wildlife Service, (FWS), is a branch of the Interior Department]. Her specialty is studying water quality in karst aquifers such as the Edwards. In 1992, Mahler, along with Dr. Mark Kirkpatrick, a biology professor at the University of Texas at Austin, petitioned the FWS to list the Barton Springs salamander as endangered. Two years ago, Mahler collected samples in Barton Springs after rain storms. “What we’re seeing is pulses of pesticides moving through after rainstorms,” Mahler says of that effort. Mahler’s research during and after a two-day rainfall detected five pesticides, some of which were still in the springs more than a week later. Mahler’s report states that none of the pesticide concentrations exceeded maximum contaminant levels, health advisories, or Texas aquatic life standards, but their presence in the springs soon after a rainfall does indicate the vulnerability of the springs to contaminant infiltration from the surface.

What’s crystal clear to anyone studying water quality or the salamander is that conditions have gotten worse over time, and will continue to worsen as more development occurs within the vast watershed that recharges the aquifer.

Nancy McClintock, manager of the Environmental Resources Management Division for the City of Austin, says the latest data indicates deterioration of the water quality in Barton Springs consistent with what happens when watersheds begin to urbanize. This is exactly the reason that the Barton Springs salamander was listed as an endangered species deserving federal protection. The rule published in the Federal Register April 30, 1997, noted, “The primary threats to this species are degradation of the quality and quantity of water that feeds Barton Springs due to urban expansion over the Barton Springs watershed.”

Development of raw land creates more impervious cover from roads, driveways, sidewalks and rooftops. This increases the volume and velocity of storm water runoff, which triggers more erosion and sedimentation. The sediments, oil and gasoline residues from the operation of motor vehicles and lawn mowers, as well as pesticides and herbicides common in developed areas, are transported by storm water runoff, entering creeks and tributaries that recharge the aquifer. The recharge that affects Barton Springs and the salamander is contributed by five major creeks in southern Travis and northern Hays counties. In the absence of a catastrophic spill of hazardous material-which could contaminate the aquifer irreparably, possibly forever-water quality in the aquifer slowly degrades as more and more urbanization adds insult upon insult to the environment.

The latest assault on the salamander was political. It happened in early May, when the FWS, the agency responsible for enforcement of the federal Endangered Species Act, turned a blind eye to the plight of the salamander.

The latest assault on the salamander was political. It happened in early May, when the FWS, the agency responsible for enforcement of the federal Endangered Species Act, turned a blind eye to the plight of the salamander.

David Frederick, who since February 1998 had been the Austin field supervisor for the FWS, was suddenly yanked off the front lines in the battle to save the salamander and transferred to the regional headquarters in Albuquerque. His regional director, Nancy Kaufman, had already been reassigned to Washington, DC, last December.

Frederick (profiled in The Good Life in November 2000) had been leading the charge in an interagency battle with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) over the EPA’s lax enforcement of permits that allow development projects to proceed without close scrutiny. To settle federal lawsuits filed by the Save Our Springs Alliance and Texas Capitol Area Builders Association, Frederick was required to draft a biological opinion regarding the EPA’s permitting system. Frederick’s draft biological opinion of July 19, 2001, concluded the permitting system “is likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the salamander.”

At stake in the interagency squabble was how the EPA was to enforce the Construction General Permit. Federal law prohibits discharges of pollutants in storm water from construction activities without a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) Permit. Operators of construction sites where five or more acres are disturbed, or smaller sites that are part of larger common plan of development or sale where there is cumulative disturbance of at least five acres, must submit a Notice of Intent to obtain coverage under the NPDES Storm Water General Construction Permit. The permit allows construction activities to go forward by filing a Notice of Intent to discharge storm water. The developer certifies that either there are no listed endangered or threatened species or critical habitat in the project area, or, if there is, that measures will be taken to protect them. As long as the developer postmarks the Notice of Intent (NOI) at least forty-eight hours before construction begins, he can start turning dirt. As the FWS’ final biological opinion states, “If the NOI is complete and the operator has certified they meet the permit eligibility conditions, construction may begin without EPA independently verifying the accuracy of the operator’s certified claim of eligibility with regard to endangered species protection.” When a profit-minded developer can take a chance on cutting corners on environmental protection, then it’s a system ripe for abuse.

This self-certification process was at the heart of earlier litigation filed by the Save Our Springs Alliance. The lawsuit alleged the EPA had failed to follow the Endangered Species Act by not consulting with the FWS regarding the Construction General Permit’s impact on endangered species. Long before the lawsuit, Frederick had sought consultation with the EPA and had, in fact, notified the EPA of the requirement for consultation in letters of October 21, 1998, and June 29, 1999, to no avail. On the other side of the same litigation was the Texas Capitol Area Builders Association, which challenged the FWS’ requests for consultation.

Despite EPA resistance, Frederick wouldn’t back off his position that the EPA’s lax enforcement of the Construction General Permit posed a threat to the continued existence of the Barton Springs salamander. Frederick’s draft opinion with a finding of jeopardy—if approved and signed by the regional director—would have required stiffer oversight of new construction projects under its General Construction Permit and new protective measures to ensure no harm to the endangered Barton Springs salamander. Further, it would have forced the EPA to go back and scrutinize construction projects already approved, a project of considerable magnitude that would no doubt have triggered howls of protest from the development community.

If Fredrick’s draft opinion were approved and signed by the FWS regional director, the storm water discharges for construction projects covered by the EPA’s General Construction Permit within the Barton Springs watershed and its contributing zone—which includes Bear, Little Bear, Williamson, Slaughter and Onion creeks—would have had to comply with either the FWS Recommendations for Protection of Water Quality of the Edwards Aquifer or the City of Austin’s Save Our Springs and Comprehensive Watershed Ordinances. Those who want to try to prevent further degradation of the water quality would say this makes perfect sense. Critics have said this would have amounted to federalizing the SOS Ordinance.

After months of interagency wrangling between the FWS and EPA, on September 5, 2001, representatives of FWS regional office in Albuquerque, the EPA regional office in Dallas, and Frederick met with headquarters staff from both agencies in Washington, DC. The meeting was called to discuss the draft biological opinion and alternatives. The official version of what happened in that meeting, according to the final biological opinion of May 6, 2002, is that the FWS and EPA “jointly agreed that the draft biological opinion would benefit from further review.”

The unofficial story of what happened in that meeting in Washington is much different. According to a federal lawsuit filed May 17 by the Save Our Springs Alliance (SOSA), political appointees in the Bush administration intervened in the September 5 meeting and stopped the FWS and EPA from reaching a negotiated settlement. If SOSA can prove this allegation in court, it could lead to the same judicial finding of “arbitrary and capricious” conduct that forced then-Interior Secretary Babbitt to list the salamander as endangered. It could also nullify the final biological opinion that concluded the EPA’s permitting system “is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the Barton Springs salamander.”

Short of a full-blown trial, the case for political interference is circumstantial. In trying to explore the validity of the SOSA lawsuit’s claims, The Good Life found that the litigation chilled the willingness of federal officials to provide information. The FWS declined to provide records requested, as documents are being gathered under a court order. Neither Frederick nor Kaufman would consent to interviews. Nor would FWS Acting Regional Director H. Dale Hall or EPA Regional Director Gregg Cooke.

Still, there is evidence. Harry Savio is executive vice president of the Texas Capitol Area Builders Association (TxCABA), an organization that has sued numerous times to stave off FWS actions viewed as overreaching federal authority. TxCABA was doing all it could to appeal to higher authority about Frederick’s proposed biological opinion that the salamander was in jeopardy, including lobbying Interior Secretary Gale Norton. “Through the National Association of Homebuilders’ Washington offices we sought intervention directly to Secretary Norton,” Savio says.

Still, there is evidence. Harry Savio is executive vice president of the Texas Capitol Area Builders Association (TxCABA), an organization that has sued numerous times to stave off FWS actions viewed as overreaching federal authority. TxCABA was doing all it could to appeal to higher authority about Frederick’s proposed biological opinion that the salamander was in jeopardy, including lobbying Interior Secretary Gale Norton. “Through the National Association of Homebuilders’ Washington offices we sought intervention directly to Secretary Norton,” Savio says.

The case for political interference also points to the fact that the final biological opinion, which declares that the EPA’s continued operation of the Construction General Permit in the Barton Springs watershed “is not likely to jeopardize the existence of the Barton Springs salamander,” is contradicted by the scientific information within the sixty-six-page opinion. For example, the report documents the drastic decline in the numbers of salamanders in recent years. It notes the salamanders’ affliction with gas bubble disease, including the fact that, “Prior to this incident, there has been no evidence of gas bubble trauma at this site.” It expresses concern for contaminants found in the water, including herbicides, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, solvents and elevated levels of nitrate. It acknowledges that areas of high-quality salamander habitat have decreased in recent years due to the deposition of silt and sediment. An accumulation of sediment covers all available habitat at Eliza Spring, and much of the other three springs are also affected. “This is a major change from historic accounts of these springs that had crystal clear conditions with little silt or sediment,” the opinion states. Heavy metals attached to sediment may have toxic effects on prey species and the salamander itself.

One reason for the contradiction between the science and the biological opinion’s conclusion is the fact that the final draft was a rush job. Although the draft opinion had been floated in various versions since July 2001, the FWS and EPA were under a court mandate, brought about to settle litigation brought by the Save Our Springs Alliance (SOSA). The settlement set target dates for action by the EPA and FWS, and required FWS to issue a final biological opinion by September 4, 2001. When that didn’t happen, SOSA filed another lawsuit, alleging breach of the settlement agreement and violation of the Endangered Species Act. US District Judge Sam Sparks did not take kindly to the federal agencies’ disregard for the settlement agreement, which he personally had approved April 27, 2001, in dismissing earlier lawsuits. Instead of complying with the terms of the settlement, the defendants contended they had entered a Memorandum of Understanding to complete consultation by July 25, 2002. The disregard for the settlement agreement Sparks had okayed raised his hackles.

Sparks grabbed the federal agencies by their legal lapels with a scathing decision filed March 26, 2002. “The court cannot fathom why an entity as resourceful and mammoth as the federal government needs fifteen months, the gestation period of a black rhinoceros, to complete a consultation concerning the effects of construction on a three-inch creature,” Sparks wrote. “The court especially cannot see any legitimate, apolitical reason the defendants need over a year—the gestation period of an ass—to finalize a draft biological opinion.” Sparks ordered the EPA and FWS to complete their consultation within forty days—or to appear for a hearing in forty days and explain why.

In noting that there was no “apolitical reason” for the delay, Sparks—who is well known for his personal disdain for the Endangered Species Act—was clearly criticizing the same sort of political interference in due process that had caused Interior Secretary Babbitt to be found guilty of “arbitrary and capricious” conduct.

The forty days Sparks allowed ran out May 6, 2002, which is the date the final biological opinion was signed by Albuquerque-based H. Dale Hall, acting regional director for the FWS. The final opinion completely reversed the strong recommendations made in the draft biological opinion rendered by the scientists monitoring the salamander’s fate in Austin, and advocated by their field supervisor, David Frederick.

Even Harry Savio of TxCABA—who adamantly opposed a biological opinion finding of jeopardy for the salamander, and filed lawsuits and lobbied to prevent it—concedes there are serious flaws in the final biological opinion. “The final biological opinion was really rushed as a result of needing to meet court deadlines in Austin, so some of the underlying work to amend the basic draft was never done,” Savio says. “The only thing that really changed was the conclusion.”

The slender thread held out to support the final biological opinion is that the EPA’s General Construction Permit will expire in July 2003 and that, considering the range of estimates for land to be disturbed during construction before then (600 to 3100 acres, depending on which of three estimates you believe), “any potential impact to the salamander is anticipated to be relatively small.”

The biological opinion concludes, in part, “…the best available information indicates that the incremental contribution of pollutants from projects covered by the permit during the next fourteen months is expected to be small, provided the permit and applicable local ordinances are followed. To ensure compliance with its permit, EPA has committed to enhanced oversight, monitoring and enforcement, in coordination with FWS Texas, and local authorities.” Case closed.

Of course this logic—that the incremental contributions of pollutants is acceptable—ignores the fact that it’s the cumulative effect of thousands and thousands of acres of development that has already occurred that has degraded water quality in the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer. The biological opinion, in effect, says what harm is a little more pollution going to do? Which is exactly the problem we face, not just for the Barton Springs salamander but for the environment we all must live in. It is the problem that Garrett Hardin wrote about in “The Tragedy of the Commons” in 1968: “The rational man finds that his share of the cost of the wastes he discharges into the commons is less than the cost of purifying his wastes before releasing them. Since this is true for everyone, we are locked into a system of ‘fouling our own nest,’ so long as we behave only as independent, rational, free enterprisers.”

Knowledgeable scientists are far less sanguine than the FWS about the fate of the salamander.

Lisa O’Donnell formerly worked for the FWS in Austin and she wrote the rule, published in the Federal Register, under which the Barton Springs salamander was listed as an endangered species. Now O’Donnell is an environmental scientist who works for the City of Austin’s Watershed Protection Department, as is Dee Ann Chamberlain. They are directly involved with the salamander and oversee the captive breeding program that has enjoyed limited success in producing offspring. “I think the species is highly imperiled,” says O’Donnell. “I agree,” Chamberlain says.

Nancy McClintock, who manages the City of Austin’s Environmental Resources Management Division, says, “I think the survival of the salamander is highly questionable unless additional protections are required.”

Environmentalists are bracing for the worst. Asked if the Barton Springs salamander will survive, Jon Beall, president of the Save Barton Creek Association, says, “Its survival is hanging in the balance. It’s too early to tell. It’s survival is going to be a combination of our community’s ability to prevent additional pollution and clean up the existing pollution.” And Barton Springs itself? “Barton Springs’ future is in lockstep with the survival of the salamander,” Beall says.

Environmentalists are bracing for the worst. Asked if the Barton Springs salamander will survive, Jon Beall, president of the Save Barton Creek Association, says, “Its survival is hanging in the balance. It’s too early to tell. It’s survival is going to be a combination of our community’s ability to prevent additional pollution and clean up the existing pollution.” And Barton Springs itself? “Barton Springs’ future is in lockstep with the survival of the salamander,” Beall says.

Is it good-bye Barton Springs, R.I.P. salamander? “If this community doesn’t wake up, that’s about all it will be,” says Bill Bunch, SOSA’s executive director and the lawyer who crafted most of the numerous lawsuits over the salamander. “The writing is clear, all over the wall.”

Mike Blizzard of Grassroots Solutions is a political consultant who works for environmental causes. He was campaign manager for passage of the City of Austin’s bond proposition in which voters approved $65 million in May 1998 to purchase some 15,000 acres of land and conservation easements over the aquifer for the express purpose of protecting water quality. That helped, but did not stem the degradation. “Anyone who regularly swims in the springs can notice a drastic downturn in water quality,” Blizzard says. “You have chunks of algae in there on a daily basis that could choke a human being, and I speak from experience. It destroys the essence of the pool…Think of people swimming in that pool and 50,000 people drinking from the aquifer, and I wonder how long we can sustain that.”

Even respected attorneys whose livelihood depends on maneuvering development projects through the rocks and shoals of governmental red tape are divided on whether the final biological opinion is adequate to protect the Barton Springs salamander. Alan Glen of Smith Robertson Elliott & Glen says, “I think the basic conclusion of the opinion is…that the state and local regulations, if implemented and complied with, are adequate to protect the Barton Springs salamander.” David Armbrust of Armbrust Brown & Davis is less certain. “I had concerns about the (draft biological opinion) because I didn’t really think the science was totally supportive of the jeopardy call, but then to just flip-flop and go this other way, I don’t know if what’s out there is adequate to protect the salamander,” Armbrust says.

As it stands now, in another year, the enforcement of the Construction General Permit will be turned over to the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (which on September 1 will be renamed the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality). TNRCC spokeswoman Adria Dawidczik said no decision had been made regarding whether the enhanced oversight, monitoring and enforcement agreed to by the EPA will be adhered to by the state agency. Thus, even the minimalist additional oversight which the final biological opinion required of the EPA may be forfeited.

Lending further credence to SOSA’s claim of political interference over the salamander is that the current administration—led by two former oil executives, President George W. Bush and Vice President Richard B. Cheney—is doing everything in its power to give industry a higher priority than environmental protection. The Bush administration, for example, wants to open up vast federal lands for energy production, ranging from the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to pristine federal lands in Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. The stated purpose is to increase domestic energy production and reduce dependence on foreign sources, but drilling on public land also puts a lot of gold in the federal coffers. On January 23, 2002, Interior Secretary Gale Norton bragged that “the department collected $11.3 billion in receipts during fiscal year 2001.” The largest source of Interior receipts: oil and gas royalties, totaling $9.3 billion. Much of these funds go to pay for conservation initiatives.

But make no mistake, the Bush administration is no friend of the environment. On June 13, the New York Times reported the Bush administration proposed changing air pollution rules to give utilities more leeway in modernizing power plants without also being required to improve their pollution-control equipment. The Bush administration only last month acknowledged the existence of global warming. Meanwhile, Interior Secretary Gale Norton has been making speeches all over the nation about the “New Environmentalism.” On Earth Day, April 22, 2002, Secretary Norton and thirteen other top Interior officials fanned out across the country to preach the gospel of the New Environmentalism, but to environmentalists, the New Environmentalism is little more than political rhetoric that varnishes the truth about what’s being done.

Rhetoric aside, it’s indisputable that in 1995, as Texas governor, Bush resisted listing the salamander as an endangered species; as president, his administration is not doing all it could to protect the salamander.

Which leaves Central Texas with a crazy-quilt patchwork of regulations that are clearly failing to do the job. The City of Austin’s SOS Ordinance covers only twenty-nine percent of the watershed that recharges the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer. The rest of the Barton Springs segment, located in southern Travis and northern Hays counties, falls under numerous political jurisdictions, including the Village of Bee Caves; the City of Dripping Springs, whose extraterritorial jurisdiction covers most of northern Hays County; the State of Texas Edwards Aquifer Rules administered by the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission; Hays County subdivision rules; and, for any new development served by the Lower Colorado River Authority’s pipeline to Dripping Springs, FWS rules agreed to in a Memorandum of Understanding. Thus, the Barton Springs salamander faces increasingly stiff odds for survival as development proceeds under whatever rules apply for the jurisdiction in which its built.

Central Texas is in the midst of a drought. Unless the area gets significant rainfall to make up the growing deficit, the aquifer levels will continue to drop, as will the flows in Barton Springs. David Johns, a hydrogeologist with the City of Austin’s Watershed Protection Department, says water quality in Barton Springs begins to degrade when aquifer levels are lower, as in a drought. “You see most dissolved constituents increase in concentration as the discharge from the springs decreases,” Johns says. He also notes that in times of drought, Upper Barton Springs tends to go dry, giving the salamanders one less place to live.

Meanwhile, massive land developments currently seeking approvals would place even heavier loads on the overburdened aquifer. As this edition went to press, the City of Austin was considering a $15 million incentive package for Stratus Properties’ 1253-acre development within Circle C Ranch, which the developer claims is grandfathered under rules in effect when the Circle C development was first planned in the mid nineteen-eighties. In addition, the Village of Bee Cave just approved a $25 million to $30 million sales tax rebate for the Hill County Galleria, a proposed mall with about 1.3 million square feet of space, at the intersections of US Highway 71, Ranch Road 620 and Bee Caves Road.

Another potential threat to the salamander and Barton Springs is the Longhorn Pipeline, which this month is scheduled to begin pumping gasoline over the recharge zone of the aquifer. Although David Frederick signed off on the pipeline project after the operators took extensive—and expensive—steps to prevent a massive spill, environmentalists nevertheless fear the worst, a spill that will contaminate the water in the aquifer forevermore.

Massive new highway projects are slated over the aquifer recharge zone. Michael Aulick, executive director of the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization that funnels state and federal funds to local highway projects, says three major highway projects are on the local horizon:

MoPac Expressway—The main lanes of Loop 1 will be extended from where they now end, south of US Highway 290, to cross William Cannon Drive, a distance of about 1.3 miles. This project will cost an estimated $10 million and should start construction about March 2003 and take two years to complete, according to Ed Collins, advanced transportation planning director for the Austin District, Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT).

SH-45 South—State Highway 45 is slated to start Phase 1 construction, consisting of two lanes of a four-lane parkway, in August 2003. This project will extend eastward from the south end of Loop 1 and connect to FM 1626 near Marbridge. This is a $12.3 million project that will take about three years to complete, Collins says.

Oak Hill Interchange—A freeway interchange is slated for the Y in Oak Hill, where US Highway 71 branches away from US Highway 290, Collins says. This is a multi-phase project that will eventually produce a flyover, so that drivers can go from Ben White Boulevard to the lakes without a stop in Oak Hill. The frontage roads are slated to begin construction in July 2004 at a cost of $20 million. The main lanes would come later at a cost of $54 million. The flyover would cost another $13.6 million and wouldn’t start construction till 2013.

These roadway projects over the aquifer cause three concerns for the environment: road construction can add contaminants from sediment; road use can produce toxic runoff, including the possibility of spills; and bigger roads ease commuting and thus open up sensitive land on the periphery for more development.

Don Nyland, area engineer for TxDOT, says traps will be designed for these roadways to catch spills of up to 10,000 gallons. Grass-lined ditches and grassy swales will be incorporated to capture and filter the runoff. In addition, detention ponds may be installed in some areas, depending on the needs identified as the highway designs evolve. During construction, filter fences and rock berms are the standard erosion controls, he says.

It’s an open question whether the measures Nyland outlined will be adequate to protect the aquifer and salamander, however. Nancy McClintock, manager of the city’s Environmental Resources Management Division, says, “They’ve never built a road out there to nondegradation standards, so we don’t know what the future holds for us in terms of state-built roads, or how the FWS might influence how those roads are built.”

A massive new water supply is also opening up in the Hill County. In mid-June, the LCRA’s $20 million water pipeline project—formally known as the Northern Hays and Southwestern Williamson County Water Supply System—began delivering treated surface water to several hundred residences in Sunset Canyon, a subdivision east of Dripping Springs on US Highway 290. This month, the Dripping Springs Water Supply Corporation (DSWSC) will take delivery of the LCRA water as its primary supply to serve almost a thousand taps, says Joel Wilkinson of Neptune-Wilkinson Associates Inc., engineer for DSWSC. To accommodate the new service, DSWSC customers’ minimum water bills will rise forty percent, from twenty dollars a month for 3,000 gallons, to twenty-eight dollars a month, he says. Wilkinson says the DSWSC’s initial cost to hook up to the LCRA line was approximately $50,000. He says he does not anticipate a large increase in demand for water, although negotiations are ongoing to possibly supply water to a development south of Dripping Springs, near the intersection of Ranch Roads 12 and 150, that would have approximately three hundred fifty lots.

Brent Covert, utility development coordinator for the LCRA, says the new water supply system has the capacity to serve 7,630 taps.

Environmentalists fought the LCRA pipeline from the beginning, fearing that a high-capacity surface water supply would promote increased density in northern Hays County. And it will do just that, in the areas that are subject to Hays County’s rules for minimum lot sizes. Under those rules, a home within the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone equipped with a septic system and a private well requires a minimum lot size of five acres. With surface water, the same home with a septic system can be put on two acres. The saving grace is that under the LCRA’s Memorandum of Understanding with FWS, any new development served from the water line is supposed to comply with Water Quality Protection Measures, including buffer zones along streams, nondegradation standards for storm water runoff, and limits on impervious cover. Densities may be increased, however, if off-site land is provided and maintained in an undeveloped condition in perpetuity.

Engineer Karen Bondy, manager of Water and Wastewater Operations for the LCRA and project manager for the water supply pipeline, offers assurance that the LCRA will abide by the terms of the Memorandum of Understanding. “Any new development has to bring a letter of approval from the FWS before we will even talk to them about a water service agreement,” she says.

Undercutting the environmental community’s faith in the LCRA’s compliance with the Memorandum of Understanding is the perception that the Environmental Impact Study (EIS) for the water supply system, produced by Utah consultants Bio-West Inc. at a cost of $400,000, is fatally flawed. And it’s not only environmentalists who are concerned. Four of the scientists who were on the Water Resources Technical Advisory Group for the Bio-West study wrote a scorching nine-page critique of the EIS in January. The critique’s final paragraph says, in part, “As a technical document, the Bio-West EIS report has numerous serious deficiencies…We feel that the current version of this report is a disservice to the technical community of Central Texas, who must live with the consequences of this document…Unless the report is thoroughly revised, we suggest that it not be released.”

The critique was signed by US Geological Survey scientists Barbara Mahler, research hydrogeologist, and Raymond Slade, Texas District surface water specialist; hydrogeologist Rebecca Morris of the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District; and hydrogeologist David Johns of the City of Austin.

Bondy is attempting to address the concerns of scientists and environmentalists over the study. Last month she wrote a letter to the Save Our Springs Alliance, for example, to address each of the organization’s criticisms. The LCRA also has hired Brigid Shea, former City Council member and former executive director of the Alliance, to help. “I’ve asked her to help us identify who in the public still would have issues and make sure we understand what those issues are, and we’ll continue to work to see if we can address those issues,” Bondy says. In addition, the LCRA has hired the Low Impact Development Center Inc., a nonprofit organization based in Beltsville, Maryland, to provide a detailed review of the Water Quality Protection Measures specified in the Memorandum of Understanding with the FWS.

So there you have it, the watered down biological opinion that allows the EPA to continue lax enforcement of the Construction General Permit; the patchwork of water quality controls over the Barton Springs segment of the aquifer; and a spate of new development, including land development, roadway projects and massive new water supplies for the hinterlands, with each project doing its share to further degrade water quality. Add it all up and next month’s celebration of the tenth anniversary of the passage of the SOS Ordinance may be dampened.

One cause for possible celebration by environmentalists, however, is the new litigation, filed June 24 by SOSA in state district court just as this edition was going to press. The defendants are Stratus Properties, its subsidiary Circle C Land Corp., and the City of Austin. Joining SOSA as plaintiff was the Circle C Neighborhood Association.

If successful, this lawsuit could strike down the state law that allows grandfathered development projects to go forward within Austin’s jurisdiction with less environmental protection than the Save Our Springs Ordinance requires. The lawsuit seeks injunctive relief and a declaratory judgment that would—if granted by the court—in one fell swoop nullify the grandfathering claims that Stratus Properties is asserting to wangle $15 million in incentives from the City of Austin.

“The Stratus deal on the table is a main target, but we’re looking at all the other grandfathered development projects in the watershed, not just in Austin’s jurisdiction,” says Bill Bunch, SOSA executive director. Bunch is being assisted in this lawsuit by attorneys Amy Johnson, a longtime environmental attorney, and David B. Brooks, who literally wrote the book on local government law in Texas.

“The Stratus deal on the table is a main target, but we’re looking at all the other grandfathered development projects in the watershed, not just in Austin’s jurisdiction,” says Bill Bunch, SOSA executive director. Bunch is being assisted in this lawsuit by attorneys Amy Johnson, a longtime environmental attorney, and David B. Brooks, who literally wrote the book on local government law in Texas.

The lawsuit argues that Texas Government Code Chapter 245 (grandfathering) rules exempt “regulations to prevent imminent destruction of property.” It asserts that groundwater, surface water and wildlife are forms of property threatened by pollution, and argues that the Save Our Springs Ordinance was enacted to protect the quality of groundwater, and thus the ordinance is exempt from grandfathering rules.

While this legal argument at first may seem farfetched and awfully late in coming, especially in view of the deal that the city struck in settling its long-running battles with developer Gary Bradley, there is a legal precedent. In 1997, developer Ken Slider sued the City of Sunset Valley seeking the right to build out two lots with more impervious cover than permitted by Sunset Valley’s Land Development Code and water quality regulations. Slider claimed that because the two lots were subdivided in 1983 and Sunset Valley’s Land Development Code and water quality regulations were enacted at a later date, his project was exempt. The City of Sunset Valley litigated this issue and won a summary judgment in December 1997. Senior District Judge Jerry Dellana ruled that the City of Sunset Valley’s Land Development Code, limiting development in watersheds and establishing variance standards and procedures for development in watersheds, is a “regulation to prevent imminent destruction of property and injury to persons” according to Texas Government Code, and thus exempt.

If SOSA’s lawsuit is able to overturn the grandfathering rules that have allowed so many thousands of acres to escape the environmental controls required by the SOS Ordinance—and that’s a big if, as this is being written—it would be a capstone to Bill Bunch’s decade of trench warfare on behalf of the aquifer and the salamander. He will be leaving in September to spend a year in Prague, Czechoslovakia, where he met his wife. “I will still be working part-time for SOS, telecommuting,” he says, “but the main reason is to finish the book I started, and learn to speak Czech and drink some Czech beer. It’s good and it’s cheap.”

But what does the future hold for the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer and the Barton Springs salamander? With respect to the FWS, only time will tell whether David Frederick’s successor as Austin field supervisor will be as aggressive about protecting the salamander and as willing to work with developers for solutions. Renne Lohoefener started work around June 1, not to replace Frederick but to oversee the entire state. Lohoefener transferred from Washington, DC, where for about two years he was chief of endangered species for the FWS. “I will be hiring Dave Frederick’s replacement,” he says. Lohoefener will oversee the field supervisors in four major FWS locations: Austin, Arlington, Clear Lake and Corpus Christi. He says he hopes to fill the Austin field supervisor’s position by around September 1. Meanwhile, Bill Seawell will continue as acting field supervisor in Austin.

But what does the future hold for the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer and the Barton Springs salamander? With respect to the FWS, only time will tell whether David Frederick’s successor as Austin field supervisor will be as aggressive about protecting the salamander and as willing to work with developers for solutions. Renne Lohoefener started work around June 1, not to replace Frederick but to oversee the entire state. Lohoefener transferred from Washington, DC, where for about two years he was chief of endangered species for the FWS. “I will be hiring Dave Frederick’s replacement,” he says. Lohoefener will oversee the field supervisors in four major FWS locations: Austin, Arlington, Clear Lake and Corpus Christi. He says he hopes to fill the Austin field supervisor’s position by around September 1. Meanwhile, Bill Seawell will continue as acting field supervisor in Austin.

As to the future direction the FWS will take, Lohoefener says, “I think we’ll keep doing what we’ve been doing. We have laws and regulations to implement and we are going to be looking to do it in a partnership with anybody that wants to work with us and we are certainly going to be looking for new ways to implement the Endangered Species Act, flexibly. We’ll be as creative as we can with our partners to get the job done, but get the job done in a way that people think they can live with it.”

One thing that Frederick constantly preached as Austin field supervisor was the need for regional planning. In fact, the Memorandum of Understanding between the FWS and the LCRA for the Dripping Springs waterline specifically called for it: “Local governments are encouraged to initiate an effort to develop a regional solution for water quality protection in the Barton Springs watershed that will assure new development will be in compliance with the Endangered Species Act with respect to the Barton Springs salamander.”

Lohoefener says Frederick’s emphasis on regional planning was warranted. “I think Dave was exactly right,” he says.

It seems FWS officials now recognize what local environmentalists have been saying for more than a generation. The Save Barton Creek Association was founded in 1979. At its twentieth anniversary party in November 1999, attorney Wayne Gronquist said regional planning was one of the founding principles of the organization. “We advocated a century plan, a preservation plan specific to the Barton Springs watershed for a hundred years.”

No such plan has been devised. Instead, the fate of the watershed rests in the hands of a host of governmental entities that don’t often work in unison, each left to its own devices to react to the flood of development projects fueled by a never-ending growth in population.

While the initial efforts to begin regional planning for northern Hays County was aborted in September 1999, there is a glimmer of hope on the horizon. Two separate initiatives are underway to develop regional plans.

One is a grass-roots effort sponsored by the Friendship Alliance of North Hays County. A few months ago, Rob Baxter, president of the Friendship Alliance, along with David Baker, executive director of the Wimberley Valley Watershed Association, sponsored a meeting of elected officials from Hays County, Hays County municipalities, the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District, and the Hays-Trinity Groundwater Conservation District. The upshot of the meeting, Baxter says, was the elected officials agreed that regional planning was needed, and they asked Baxter and Baker to draft a resolution calling for the appointment of a Blue Ribbon Committee to work on a regional plan for north Hays County. The draft resolution would require a unanimous vote by the Hays County Commissioners Court, Baxter says.

Hays County Judge Jim Powers attended the meeting hosted by Baxter and Baker. “I feel like we desperately need to move the process forward,” Powers says. “I think regional planning for water quality is an important issue that we need to really focus on, so we can find new ways and better ways of not only protecting the environment, but also providing good clean water to the citizens of Hays County.” It’s unclear when the resolution to appoint a Blue Ribbon Committee might be ready for the Hays County Commissioners Court to consider, Powers says, as the county budget is absorbing their attention at present.

More promising is the work being done by the Central Texas Regional Visioning Project. A board comprised of nearly seventy members was announced in February, under the leadership of Chairman Neal Kocurek. The board has representation from all five counties in the metropolitan area and a broad range of constituencies, including business, elected officials, equity, environment, neighborhoods, and strategic partners.

One member of the board is Jon Beall, president of the Save Barton Creek Association. He says the Visioning Project will help protect water quality. The larger question the Project is going to try to address, Beall says, is “Where are we going to put the next 500,000 people? If we decide we don’t want to put them over the aquifer, it’s going to have benefits for the entire region.” Beall says the Visioning Project has already been funded to the tune more than a million dollars and is professionally managed by Fregonese Calthorpe Associates, regional and urban planning consultants based in Portland, Oregon, and Executive Director Beverly Silas. “All my conservative friends get a little nervous when they hear I’m involved” in the Visioning Project, Beall says, “and there’s a little nervousness from my progressive friends when they hear Neal Kocurek is involved. So everybody who’s not involved is nervous that it’s going to be controlled by the progressives or by the conservatives, but it’s really a very good process.”

Beall believes the Visioning Project will eventually need to ask the Texas Legislature for enabling legislation to implement regional planning. “First we want to come up with a plan. Then it will be up to the region and its elected officials to implement,” he says. At this stage, he says, it’s not clear what the Legislature will be asked to do, but one thing is clear: the state will not be asked for more money. “It will require some kind of regional body authorized by the Legislature where our sixty different political subdivisions (including counties, municipalities, school districts, water districts, and others) are brought together under some kind of regional authority.”

Whatever kind of plan surfaces, if it brings allies to the City of Austin’s long-running efforts to protect the environment, that would be a welcome change, says City Council Member Daryl Slusher. “The City of Austin over the last five years spent $65 million on the purchase of land (to prevent growth over the aquifer),” Slusher says. “There hasn’t been any help from the state, no help from the federal government and no help from any surrounding jurisdiction. All that land over the aquifer has been purchased by the City of Austin. So we need more players participating, not just in the planning, but in implementing the plan.

“The plan is simple: buy some land, have strong water quality protection ordinances, steer development off the aquifer like the City of Austin’s been doing, and clean up your existing pollution sources,” Slusher says.

Cleaning up existing pollution is the goal behind the Austin City Council’s recent resolution asking city staff to identify the top ten sources of pollution for Barton Springs. Environmental Resources Manager Nancy McClintock says the staff is still grappling with how to accomplish that task, but hopes to present the council with a proposed approach later this summer. Retrofitting projects are both expensive and difficult, McClintock notes. A 1995 study estimated a cost of $11 million for about twenty-six projects that collectively would make only a small improvement in water quality in Barton Springs, she said.

McClintock says some retrofitting projects will be done, but emphasis will be put on educational programs such as the Grow Green Program that encourages the use of plants that reduce the need for pesticides, fertilizers and watering, and provides less toxic solutions to landscaping problems.

Educating and gaining cooperation of the large population that resides over the recharge and contributing zones of the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer will be a monumental task. But in the long run, we can only undo the tragedy of the commons, and clean up the fouling of our nest, if we all do our parts. If not, the salamander’s fate appears to be sealed, and perhaps with it the water supply upon which 50,000 people depend for daily sustenance.

And what of Barton Springs? The three-acre pool is the crown jewel of Zilker Park, named for Andrew Jackson Zilker, who bought the land in 1901. The place that Native Americans called the Sacred Springs and visited to heal their wounds has offered nourishment and respite for hundreds of years. The place we call the Soul of the City may in time become little more than a silt-filled and contaminated relic of the past. And what are we, if we lose our soul?

Ken Martin, editor of The Good Life, recalls the words of Roman emporer and philosopher Marcus Aurelius: “That which is not good for the beehive cannot be good for the bees.”

Barton Springs is the fourth largest spring in Texas, exceeded only by Comal, San Marcos and San Felipe. There are four spring outlets at Barton Springs: Pathenia (the main spring, in Barton Springs Pool); Eliza (also known as Elks, adjacent to the concession stand); Sunken Garden (also known as Old Mill or Walsh, located on the south side of the pool); and Upper Barton Spring, located in Barton Creek immediately upstream from Barton Springs Pool. Today, only Upper Barton Springs is not impounded in concrete.

1901—Andrew Jackson Zilker purchases the land which includes what Native Americans had called Sacred Springs, a place they visited to heal their wounds. At the site of one of the springs, Zilker soon builds a small concrete pool and amphitheatre for members of his Elks Club organization.

1917—The property becomes a city park.

1929—The area around the main spring outlet is impounded to create Barton Springs Pool, a thousand feet long, enclosed by a concrete lower dam and sidewalks on both sides.

1932—The city adds an upper dam.

1946—The Barton Springs salamander is first collected from Barton Springs Pool by Bryce Brown and Alvin Flury.

1978—Dr. Samuel Sweet of the University of California at Santa Barbara is the first to recognize the Barton Springs salamander as distinct from other Central Texas Eurycea salamanders based on its restricted distribution and unique morphological and skeletal characteristics (such as its reduced eyes, elongate limbs, dorsal coloration, and reduced number of presacral vertebrae).

1979

(1) Construction begins on Barton Creek Square Mall. Dorothy Richter, who swims daily at Barton Springs Pool, says, “The first time I noticed the springs running muddy was when they dynamited the hill to build Barton Creek Square Mall.” The mall is built on Loop 360 above Barton Creek with more than 1 million square feet of retail space and enough parking for a major airport. In response, Richter and others form the Zilker Park Posse, a coalition of groups. In September 1979, attorney Wayne Gronquist files the paperwork to incorporate the Posse and form a political action committee.

(2) The Save Barton Creek Association is formed.

1981—The Barton Creek Watershed Ordinance is enacted. Bond proposals that would have extended water and wastewater service into this sensitive watershed are defeated.

1982—The US Department of Interior on December 30 recognizes that the Barton Springs Salamander might be endangered or threatened, and listed the species as a “Category 2” candidate.

1990—The Austin City Council holds an all-night hearing at which 800 people sign up to speak, most in opposition to Freeport-McMoRan Inc.’s proposal to build a 4,000-acre development on Barton Creek. The council votes unanimously to reject the development proposal.

1991—The Save Our Springs Coalition forms to gather signatures needed to put the Save Our Springs Ordinance on the ballot.

1992

(1) On January 22, Mark Kirkpatrick and Barbara Mahler petition the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to list the Barton Springs salamander as an endangered species and to designate critical habitat for the species.

(2) On August 8, the Save Our Springs Ordinance is approved by voters by a margin of 42,246 to 26,187. Voters reject an alternative proposition the council had put on the ballot by 44,556 to 24,140.

(3) On December 11, the FWS publishes a finding in favor of adding Barton Springs salamander to the Endangered Species Act.

1994—FWS publishes in the Federal Register a proposal to list Barton Springs salamander as an endangered species.

1995

(1) The Save Our Springs Legal Defense Fund (SOSLDF) files suit asking the court to force US Secretary of Interior Bruce Babbitt to make a decision on whether to list the Barton Springs Salamander as an endangered species.

(2) Texas Governor George W. Bush’s letter of Feb. 14 expresses “deep concerns because the proposed action by the federal government may have the potential to impact the use of private property.”

1996

(1) On July 10, Judge Bunton grants SOSLDF motion for preliminary injunction and orders Secretary Babbitt to make a decision on whether to list the salamander as endangered, withdraw the listing, or extend the time to make a decision by no more than six months.

(2) The Barton Springs Salamander Conservation Agreement and Strategy is signed August 13 by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission, the Texas Department of Transportation, and FWS.

(3) On September 14, Babbitt withdraws the proposed rule to list the salamander as endangered because of the commitment of the state of Texas to the Conservation Agreement.

(4) SOSLDF files suit October 29 challenging Babbitt’s decision to withdraw the proposed listing of the Barton Springs salamander.

1997

(1) On March 25, Judge Bunton rules on the SOSLDF lawsuit and remands it to the Secretary to make a listing determination with respect to the Barton Springs salamander consistent with this opinion not later than 30 days from the date of this order, stating, “The ESA requires the Secretary to disregard politics and to make listing decisions based solely on the best scientific and commercial data available…The court finds as a matter of law that the Secretary’s decision to withdraw the listing of the Barton Springs salamander was arbitrary and capricious and that the Secretary relied upon factors other than those contemplated by the Endangered Species Act.”

(2) The Federal Register of April 30 lists the Barton Springs salamander as an endangered species.

1998

(1) The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issues a General Construction Permit on July 6, which regulates the effects of construction and development on endangered species, including construction in the recharge and contributing zones of the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer.

(2) On October 21, the FWS requests consultation with the EPA regarding the Construction General Permit’s effect on the Barton Springs salamander.

1999

(1) On March 26, the Texas Capitol Area Homebuilders Association (TxCABA) files suit against the Department of Interior and FWS, challenging the FWS’ request for consultation with the EPA.

(2) On June 29, the FWS for the second time requests consultation with the EPA regarding the permit’s effects on the Barton Springs salamander.

2000—The SOS Alliance (SOSA) files suit against the EPA on June 15, challenging the failure to consult with the FWS regarding the General Construction Permit’s effects on the salamander. US District Judge Sam Sparks consolidates the TxCABA and SOSA cases.

2001

(1) All parties to the lawsuit execute a settlement agreement filed in court April 23. Judge Sparks dismisses the cases without prejudice pursuant to the agreement on April 27. Under the agreement, the EPA agrees to request initiation of the consultation with the FWS beginning within 14 working days of the execution of the agreement and the FWS agrees to provide a draft biological agreement within 30 days of receiving certain information from the EPA.

(2) On July 19, the FWS issues a draft biological opinion stating the Construction General Permit is likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the salamander, and would require additional protective measures to be instituted.

(3) On September 5, FWS, EPA, and Department of Interior (DOI) officials meet in Washington, DC, to discuss the draft biological opinion and alternatives.

(4) In December, FWS Regional Director Nancy Kaufman is reassigned to Washington, DC.

(5) On December 17, SOSA files a lawsuit alleging EPA, DOI and FWS breached the earlier settlement agreement and violated the Endangered Species Act.

2002

(1) A workshop jointly sponsored by EPA and FWS is held in Austin March 27-28 to gather comments on the draft biological opinion, focusing on the hydrology and water quality of Barton Springs Recharge and Contributing Zones as well as the biology of the Barton Springs salamander.

(2) Defendants in the SOSA lawsuit of December 17 move to stay proceedings in this case until July 25, when they contend they will have completed the consultation. They provide a Memorandum of Understanding in which EPA and FWS agree to complete their ESA consultation regarding the effects of the permit on the salamander by July 25. Meanwhile, development will continue under the permit.

(3) On March 26, Judge Sparks slaps down the motion to stay the proceedings, writing, “Apparently the defendants expect this court to believe the self-imposed date they set in the Memorandum of Understanding will be more effective than the date they selected in the Settlement Agreement in order to convince this court to dismiss two complex lawsuits against them. The court is not convinced the defendants can abide by any deadlines, much less self-imposed ones, and the defendants have not provided the court with any plausible reason for the delay. The consultation was to have begun approximately 11 months ago. The defendants claim they need until July 25, 2002, to complete the consultation. The court cannot fathom why an entity as resourceful and mammoth as the federal government needs 15 months, the gestation period of a black rhinoceros, to complete a consultation concerning the effects of construction on a three-inch creature. The court especially cannot see any legitimate, apolitical reason the defendants need over a year—the gestation period of an ass—to finalize a draft biological opinion. Almost seven months have passed since the defendants were obligated to complete the consultation under the terms of the settlement agreement and the court sees no reason to condone further delay.” Judge Sparks orders the EPA and FWS to complete their consultation regarding the effects of the EPA’s Construction Storm Water General Permit on the Barton Springs salamander within 40 days.

(4) On May 6, a final biological opinion is signed by H. Dale Hall, acting regional director of FWS. The opinion states “…the continued operation of the Construction General Permit in the Barton Springs watershed, as proposed, is not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of the Barton Springs salamander.”

(5) On or about May 6, FWS Austin Field Supervisor David Frederick is reassigned to the regional headquarters.

(6) On May 17, SOSA files suit, claiming the final biological opinion is “arbitrary and capricious.”

(7) On June 24, SOSA files suit against Stratus Properties, its subsidiary, Circle C Land Corp., and the City of Austin, seeking a court ruling that the SOS Ordinance is exempt from grandfathering rules under state law.

Phillip Martin, deputy director at

Phillip Martin, deputy director at  The District 6 candidates started the opening remarks. Matt Stillwell, whose

The District 6 candidates started the opening remarks. Matt Stillwell, whose  Jimmy Flannigan said the relationships he has built through working with the Austin Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce made him stand out among the other candidates.

Jimmy Flannigan said the relationships he has built through working with the Austin Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce made him stand out among the other candidates.