About 11,100 words

About 11,100 words

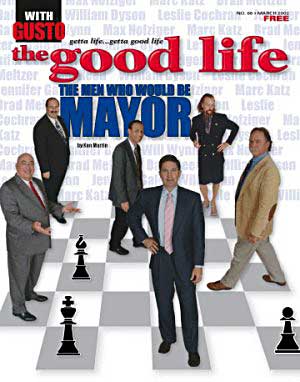

The men who would be mayor deserve close public scrutiny

By the time this edition of The Good Life was going to press February 23, 2003, eight men (and no women) had declared their intentions to compete for the honor of succeeding Gus Garcia as mayor of Austin. Not all of them had actually filed a formal application for a place on the general election ballot, but we felt confident enough of their intentions to spend time interviewing the best and brightest among them. It’s likely that before the filing period closes March 19, others will venture into the arena to offer their services. If so, we will examine their qualifications and if any latecomers seem worthy, we will publish their profiles in the April edition.

Under the Austin City Charter, to run for office, candidates shall be eighteen years of age or older on the commencement of their term, shall have resided within the city for at least six months and within the State of Texas for at least twelve months, and shall be a qualified voter of the State of Texas. That’s it. Those are the minimum qualifications. Obviously the city needs someone who has considerably more than that to offer as mayor, the point person for city policy and the de facto leader of the Austin City Council, despite the fact that the mayor has no more voting power than the six other members of the council. We need to elect someone who not only envisions what needs to be done but also possesses the political skill to persuade the other city council members and garner their support.

These are tough times. The economy is lagging. Sales taxes are down. And next year promises to be worse for city revenue because commercial property values are expected to fall. Austin needs a decisive leader. Do we have a candidate who can pull us together like Churchill during the blitz? Who can challenge and inspire us to compete like Kennedy during the race for outer space? Someone with a cool head and a clear mind who will stand up not to the ravages of war (though a war may soon be raging on foreign soil) but a ravaged economy? These are high standards, indeed, but from among those willing to try we need to discern who best measures up.

While anyone who meets the minimum qualifications can get on the ballot, we are exercising our right under the First Amendment to focus primarily on those who have something substantial to offer. Which is why we direct your attention to the four candidates profiled in our cover story: Marc Katz, Brad Meltzer, Max Nofziger, and Will Wynn.

For the record, four other people have stated their intention to run for mayor. These are Leslie Cochran and Jennifer Gale, both of whom have filed for a place on the ballot; William Dyson, who has appointed a campaign treasurer; and Dale Reed, who published a campaign ad in the Valentine’s Day edition of The Austin Chronicle.

Both Cochran and Gale are homeless persons with whom the public is already well acquainted, as they are perennial candidates who have added nothing substantive to the public discourse.

Dyson is a new face in local politics. He is forty years old and says he was born in Norfolk, Virginia, is the son of an African-American minister, and has a degree in political science from Norfolk State University. He has lived in Austin since 1993, he says. After being laid off for eight months, he says he recently got a job at a software company in Round Rock, but couldn’t provide the company’s address. He says he has never been to a city council meeting or watched one on television. When interviewed, he exhibited no grasp of local political issues and was hesitant to provide the names of anyone who could be asked about his qualifications. Hence, he was not profiled.

Reed, along with Cochran and Gale, ran against Mayor Kirk Watson when the incumbent sought reelection in 2000. Watson got 84.03 percent of the vote, Cochran got 7.77 percent, Reed got 4.69 percent, and Gale got 3.51 percent. The telephone number Reed provided to the city clerk’s office has been disconnected and he could not be reached for interview, but we noticed that his campaign ad in the Chronicle solicits donations in various categories ranging from $100 to $10,000, despite the fact that donations of more than $100 are prohibited. Mike Clark-Madison reported in the Chronicle last month that Reed is a cab driver who in the 2000 election called “for more, not less, development in western Travis County and for building a water treatment plant to purify Barton Springs.”

Getting to the meat of the matter, as the field now stands, voters may choose the next mayor from among four men who will undoubtedly run strong campaigns. Two of these have council experience (Nofziger, a veteran of nine years on the council, and Wynn, who is finishing his first term). The other two, Marc Katz and Brad Meltzer, have strong business backgrounds and have never before run for office.

That’s the introduction. To get a good sense of the candidates, check out the profiles.

And don’t forget to vote. The early voting period runs from April 16 to April 29. May 3 is the general election day. You must be registered to vote at least thirty days before casting your ballot.

William Patrick Wynn was born in Beaumont on September 10, 1961, while just down the Texas coast Hurricane Carla was battering the shoreline with winds gusting to one hundred seventy miles per hour. Now Wynn faces the whirlwind of Austin politics as he seeks to become Austin’s next mayor.

William Patrick Wynn was born in Beaumont on September 10, 1961, while just down the Texas coast Hurricane Carla was battering the shoreline with winds gusting to one hundred seventy miles per hour. Now Wynn faces the whirlwind of Austin politics as he seeks to become Austin’s next mayor.

“I have this significant itch that I want to scratch,” says the Austin City Council member. He holds up a thumb and forefinger separated by an inch of air, and says, “I happen to think this is going to be a very defined period of my life. I would be very surprised if I’m in public office or attempting to be in public office in my fifties.”

Professing no ambition to rise politically beyond the office of mayor, Wynn says, “This really does come down to my self-serving goal of my kids having the option to come back to their hometown as young adults.”

Wynn felt he didn’t have that option in Beaumont, a city of slightly more than 100,000 people that hasn’t grown much, if at all, since his childhood. Even as a boy he knew he would leave and never come back to live in what some folks think of as the armpit of Texas. “It’s not a coincidence that my children were born in Austin,” Wynn says.

Like all candidates, Wynn faces significant financial obstacles in trying to get his message to the public. Austin’s restrictive campaign-finance rules—which were approved by seventy-two percent of voters in November 1997, and which narrowly survived repeal by voters in May 2002—limit a candidate’s acceptance of contributions to $100 per donor. That the contribution limits are overly restrictive is illustrated by the fact that it would cost about $110,000 to send a single postcard to each of Austin’s 425,000 registered voters, according to Wynn’s figures. Hence Wynn’s vocal disdain for the contribution limits, which he more than once referred to as “anti-democratic” and “unconstitutional.”

“Two classes of people benefit from the $100 limits,” Wynn says, “incumbents and the people who have access to money, and I happen to be both.” Yet Wynn points out that he led the charge to get repeal of the donation limits on the ballot. While voters chose to retain the limits, if elected mayor, Wynn says he will try again. “Every time there is a charter election, I will be challenging my colleagues and the citizens to once and for all, let’s correct the problem we have.”

“I spent all day, every day for seven weeks on the phone,” Wynn says of the 2000 council campaign. His effort netted more than seven hundred contributions totaling $70,000, a fair sum, but still not enough. Which is why he ponied up more than $90,000 of his own money in running for the council position he now occupies. (It was only last year that he finally settled a $91,400 loan outstanding from that campaign.)

For the mayoral campaign now underway, Wynn hopes to raise about $175,000. That’s a mere fraction of the $750,000 that Kirk Watson raised for his 1997 campaign against Council Member Ronney Reynolds, before donation limits were imposed. Wynn had raised just $8,750 through the reporting period ending December 31, but he did not formally kick off the campaign until February 4. For that event, Miguel’s La Bodega downtown was crowded with more than two hundred supporters, many of whom presented checks.

Wynn will use part of his campaign budget for consultants David Butts and Pat Crow, and campaign managers Mark Nathan and Christian Archer. Nathan and Archer worked in the ill-fated 2002 Texas gubernatorial campaign of Democrat Tony Sanchez.

While Wynn seems genuinely outraged by the current campaign finance laws that govern Austin elections, these rules undeniably give wealthy individuals like him a big advantage over less affluent candidates. His wealth allows Wynn to live in a West Austin home valued at more than $1.3 million, while giving his council duties full-time attention and earning little or nothing from business endeavors.

“I like to say that I made my money the old-fashioned way—I married it,” says Wynn. Wife Anne Elizabeth Wynn is the daughter of Melbern G. and Susanne M. Glasscock, who endowed the Center for Humanities Research and a number of other academic activities at Texas A&M University. Her father is president and chief executive officer of Houston-based Texas Aromatics LP, a firm that markets byproducts from refineries and petrochemical operations. Anne Elizabeth Wynn is part owner of that company, says Will Wynn.

To avoid a conflict of interest while on the city council, within six months of taking office Wynn had sold his interest in Block 42 Congress Partners Ltd., the entity under which Wynn and partner Tom Stacy assembled the land in the 400 block of Congress Avenue, and where a thirty-three-story office building is now under construction. That transaction netted Wynn capital gains of $500,000, according to his financial disclosure statement filed with the city. Wynn is still involved in two other partnerships, both involving ownership of buildings in East Sixth Street’s entertainment district.

Wynn left Beaumont at the age of eighteen and never looked back. He lived with an older brother in northeast Austin and earned a degree in environmental design from Texas A&M University’s College of Architecture on a work-study program, in which he alternated between classes in College Station and interning with Austin-based Shefelman & Nix Architects. While at Shefelman & Nix, located at Eighth and Congress, he often observed the construction of the twenty-story office building at Ninth and Congress. As it turned out, a decade later he would come back as project manager to rehabilitate that structure’s crumbling façade.

In the interim, he spent three years in Chicago with a commercial real estate firm, enjoyed a short stint as a graduate student at Harvard University, and even spent a summer working in Governor Bill Clements’ budget office. In 1988, he moved to Dallas to work for R.D. Stone Interests (later Faison-Stone Inc.). In 1991, he became project manager for the renovation of what would become Frost Bank Plaza, and moved to Austin in 1994. In 1997 he left Faison-Stone to form his own company, Civitas Investments (civitas being Latin for citizenship), and restored two historic buildings on East Sixth Street.

While serving as chair of the Downtown Austin Alliance, Wynn launched his campaign for Place 5 on the city council, and nudged out four competitors to win the May 6, 2000, election with 50.53 percent of the votes, narrowly avoiding a runoff.

Now a council member for just shy of three years, Wynn has punched practically every possible ticket en route to the city’s top elected post. Much of his energy goes into finding regional solutions to Austin’s problems. Wynn currently chairs the Greater Austin-San Antonio Corridor Council, a private, nonprofit corporation that seeks to manage growth from a regional perspective. Wynn helped to found Envision Central Texas, a body that seeks to build a public consensus for regional planning in Central Texas; he now sits on the organization’s sixty-six member executive committee. He is a member of CAMPO’s (Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization) Policy Advisory Committee of twenty-one members; CAMPO coordinates regional transportation planning and approves the use of federal transportation funds within the Austin metropolitan area. Wynn also chairs the Coordinating Committee for the Balcones Canyonlands Conservation Plan, whose mission is to complete and manage the Balcones Canyonlands Preserve, more than thirty thousand acres of habitat for endangered species.

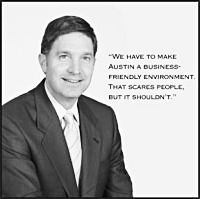

A more recent initiative that Wynn chairs is the Mayor’s Task Force on the Economy, whose recommendations for re-booting business activity in the wake of the dot-com bust are scheduled to be presented to the city council this month. For Wynn, the bottom line, is “We have to make Austin a business-friendly environment. That scares people, but it shouldn’t.”

One way to make the climate for business better is to ease the red tape that businesses encounter, Wynn says. He ran the city’s gauntlet himself in rehabilitating properties on East Sixth Street. Now he’s involved in helping to facilitate the reopening of The Tavern at Twelfth and Lamar. Rather than trying to revise the city’s massive development regulations—an effort that foundered under its own weight the last time around—Wynn says the city staff must change its mind-set. Mike Heitz, director of the Watershed Protection and Development Review Department, is personally overseeing The Tavern project to boil down the complexities to a few manageable variances, Wynn says. That project could provide a template for other projects to follow through the regulatory maze.

A friendly business environment must be balanced with protecting the natural environment, Wynn says. This would be done by stopping development where it is inappropriate. He says his message to land developers in environmentally sensitive areas is, “How can I help you be successful someplace else?” He wants to continue offering incentives to build downtown to balance the differential of what it costs to build elsewhere.

As a city council member, Wynn has been vocal about cutting expenses in the face of revenue shortfalls caused by shrinking sales taxes and declining commercial property values. He cut his council staff in half (from two positions to one) and tried to stave off an additional $500,000 allocation for the Austin Music Network. None of the other council members followed his lead. No one else reduced their staff. No one else opposed the funding.

While cutting his staff saved a few bucks it also cut Wynn’s responsiveness to constituents. E-mails have at times stacked up, unanswered, especially when hot-button issues hit the council agenda, such as the anti-war resolution the council passed (with Wynn and Betty Dunkerley abstaining). Those who try to reach his office by telephone are sometimes frustrated because Wynn’s voice-mailbox is full and can’t accept a message.

Regarding the Austin Music Network, Wynn made no effort to visit with other council members in advance. He instead used the council dais as a soapbox to argue that with the city facing a $60 million budget shortfall, it was time to pull the plug. While his cause was just—the Austin Music Network was supposed to have become self-sufficient long ago, and despite getting $4 million in city funding over the years hasn’t even come close—his tactics were an abject failure. “Privately, I believe all my colleagues knew what my position was going to be. I didn’t try to persuade them…My colleagues had made up their minds long before my argument.”

Wynn points to other instances in which he has exercised what he views as fiscal prudence, despite lack of support from his colleagues. He came out on the short end of the vote in March 2001 when the council voted 5-2 to pay Browning-Ferris Industries (BFI) about $600,000 for property it had purchased in South Austin for a new recycling facility. The motion also granted BFI $200,000 in credit to use the city’s recycling center. The council majority’s position was to support neighborhood opposition to that site. Ironically, BFI had purchased the South Austin site only after the city forced it to abandon a recycling center in East Austin, and had paid the company $3.9 million for the East Austin site. Ultimately, BFI wound up putting its recycling facility in Manor. Wynn says the city still owns the South Austin site and it’s worth about a third of what the city paid for it. “We need that $800,000 now,” Wynn says.

Wynn says the city must do more to save funds by cooperating with other governmental entities, such as it did recently by agreeing to let Travis County run city elections. If elected mayor, Wynn promises to reduce the mayoral staff, as he did his council staff.

While he laments the lost opportunities to save taxpayers money, Wynn also thinks the council has fallen short in other areas. Noting that he is including himself in this criticism, Wynn says, “We all give lip service that we want to fight suburban sprawl, yet the council is pretty damned consistent at fighting density. Sprawl has one enemy and one enemy only, and that’s density. We say we’re out to fight suburban sprawl yet we tend to fight density even where in my opinion density is appropriate…I looked it up, density is a seven-letter word, not a four-letter word.”

A trait that Wynn readily acknowledges is that he sometimes loses his temper. “I react stronger than the situation calls for occasionally. I won’t try to make excuses for that for anybody, but I think there’s always going to be some of that when you’re out trying to accomplish a lot and you get frustrated, whether it be with a bureaucracy or a rule or constraint that you think shouldn’t be there.”

The overriding issue in this campaign, Wynn says, is the city’s budget deficit. “We have to work on the budget and that will be painful,” he says. The budget ax may chop city jobs that are currently occupied. “It would not surprise me to see true layoffs,” Wynn says.

Wynn and his wife chaired the 2002 fund-raising campaign for Planned Parenthood, and he supports city funding for women’s reproductive healthcare.

Once past the budget crisis, Wynn wants to work on long-term goals including a new downtown library and converting the defunct Seaholm Power Plant to civic use. He wants to complete a number of transportation initiatives including a commuter rail district, regional mobility authority, and construction of State Highway 130 to include rail freight. To ease traffic congestion and reduce air pollution, Wynn advocates installing high-occupancy vehicle lanes on both I-35 and MoPac Expressway and promoting an aggressive campaign to encourage carpooling.

Wynn, who endorsed the light-rail proposition that was narrowly defeated in 2000, says he still supports it, along every other form of mass transportation possible.

Wynn says he supports the concept of a hospital district that would make funding of healthcare more equitable within Travis County. “We have a very inequitable public healthcare financing system and we’ve got to begin to fix it. I think the first rational step is a countywide system,” he says.

Regarding Mayor Gus Garcia’s proposal to stiffen the city’s no-smoking rules, Wynn says he has not seen the details but has two concerns. First, it would be inequitable to treat bars differently from bars and grills, he says. “It seems to me that if it’s a health issue, it should be a health issue whether you’re a bar or a restaurant.” Secondly, he says, many restaurants have opened recently and followed the city’s existing ordinance, “spending tens of thousands of dollars” on ventilation systems. “If we change the ordinance, the recent additional investment would be made worthless. Fair play tells me that we should have an objective analysis and discussion about that.”

At root, Council Member Will Wynn is well connected to a number of heavyweight organizations and wealthy enough to run a strong campaign, but seems to have more going for him than the typical candidate from the business sector. He says he moved to Austin permanently because of singer-songwriter Guy Clark—even claims he knows the lyrics to all of Clark’s songs—and was a “quiet, dues-paying member” of the Save Our Springs Alliance before joining the council. We will find out May 3 whether Wynn’s healthy dose of self-effacing Aggie charm laced with a penchant for fiscal discipline will play well with voters who pick Austin’s next mayor.

Political warhorse Michael Eddie “Max” Nofziger, a fifty-five-year-old (this month) former Austin City Council member, has heard the bugler’s call to the starting gate and he is once again charging after the votes needed to become Austin’s mayor. This is Nofziger’s ninth run for a seat on the council dais—and his fourth bid to be mayor—since he began running for political office in 1979.

Political warhorse Michael Eddie “Max” Nofziger, a fifty-five-year-old (this month) former Austin City Council member, has heard the bugler’s call to the starting gate and he is once again charging after the votes needed to become Austin’s mayor. This is Nofziger’s ninth run for a seat on the council dais—and his fourth bid to be mayor—since he began running for political office in 1979.

In each of his three previous mayoral campaigns (1983, 1985 and 1997) Nofziger garnered enough votes to force a runoff between two other candidates. “This time, of course, the goal is to get in a runoff, not just create one,” he says.

After finishing far behind Kirk Watson and Ronney Reynolds in the 1997 mayoral election, Nofziger chose not to run for mayor in 2000, when Kirk Watson was reelected in a landslide against feeble competition, or in 2001, when former Council Member Gus Garcia won the special election to succeed Watson. By June when the new mayor is sworn in, Nofziger will have been out of elective office seven years. During that time, he made a television commercial for Chevrolet trucks and helped to find a buyer for the Cinema West porn theater on South Congress, which led to the building’s renovation as an office building. From April 1998 through December 1999, Nofziger was employed by the Austin Police Department to help stop prostitution on South Congress Avenue, earning $20,425 per year in a job funded by a U.S. Department of Justice grant for community policing.

Despite his years away from the council dais, Nofziger can claim far more experience in governing than other candidates in this race; he spent nine years on the council before stepping down in 1996. Nofziger says the city’s current fiscal crisis and downbeat local economy are similar to conditions when he first took office in 1987. “I have the experience to do this. I’ve done it before,” he says. “I’m willing to offer my knowledge and my experience to the citizens of Austin and tell them that I’m the best one to help us get through these difficult times.”

Nofziger’s credibility as a political strategist got a boost from his role in defeating the light-rail initiative in November 2000, a campaign in which he acted as a consultant to longtime rail foe Gerald Daugherty and retired high-tech executive Jim Skaggs. Although vastly outspent by rail advocates, their slogan, “No Rail: Costs Too Much, Does Too Little,” proved unbeatable. The proposition failed by fewer than two thousand votes out of more than a quarter-million cast. Daugherty used that victory as a springboard to win the Precinct 3 seat on the Travis County Commissioners Court last November, despite bad press over numerous tax liens.

Nofziger continues to consult for those who oppose light rail. His new client is the Save South Congress Association. The group formed a year after the light-rail referendum failed, voicing concerns that Capital Metro has continued planning for a Rapid Transit System that members view as potentially detrimental.

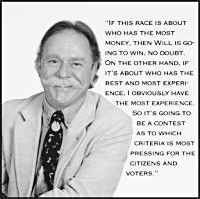

In the mayoral campaign, Nofziger knows he will be outspent by several other candidates and hopes to pull off the same sort of upset that defeated the light-rail measure. Noting that Council Member Will Wynn is the most formidable opponent he faces in this campaign, Nofziger says, “If this race is about who has the most money, then Will is going to win, no doubt. On the other hand, if it’s about who has the best and most experience, I obviously have the most experience. So it’s going to be a contest as to which criteria is most pressing for the citizens and voters.”

Nofziger says he hopes to raise between $50,000 and $100,000 for this election, far less than viable mayoral candidates typically spend. His relatively cheap campaign may be effective because he’s already well known, eschews spending money on consultants, and runs a mostly do-it-yourself operation. His campaign manager, Christine Buendel, is a paralegal who’s never before run a campaign, but Nofziger says she’s detail-oriented and organized, which is all he needs.

Nofziger says his roots run six generations deep in the tiny town of Archbold, Ohio, a Mennonite community where his ancestors arrived as early settlers in 1834. But like many a young man who came of age during the Vietnam War, he had a yen to wander. He moved around the country, living briefly in Florida, Denver, and Houston. He first hit Austin when he was hitchhiking through in 1973 and moved here permanently the next year, supporting himself by peddling flowers at South Congress and Oltorf.

“I was looking for my place, and as soon as I got to Austin I knew this was it…For me it was the music—the first night was unbelievable—and then we went out on Barton Creek skinny-dipping and Lone Star sipping, and I recognized immediately, this is paradise…It’s interesting how my first two influences, music and the water, Barton Creek in particular, have informed my politics over the years and have been a key part of what I’m trying to do here in Austin, preserve the water and preserve the music.”

By 1979, Nofziger had joined the movement to oppose voter approval for the South Texas Nuclear Project—a power plant that got built anyway, suffering enormous cost overruns in the process—and began campaigning for city council. It would be eight long years and five tries on the ballot before he finally got elected in 1987, upsetting business candidate Gilbert Martinez in a runoff. That a flower salesman could get elected to our governing body is part of Austin’s “weird” past. (Actually for years we had two flower peddlers as perennial candidates for city council. What differentiated Nofziger from “Crazy” Carl Hickerson-Bull is that Nofziger had a degree in political science from Adrian College in Adrian, Michigan, and spoke to the issues.)

As a council member, Nofziger claims credit for a long list of environmental accomplishments. Among these are introducing the first nondegradation water-quality ordinance, backing the defense of the Save Our Springs Ordinance all the way to the Supreme Court, appointing Earth First! activist Tim Jones to the city’s Environmental Board (he’s still there, by the way), and creating the city staff position of pedestrian coordinator.

While hoping that voters will recall his own contributions to environmental protection, Nofziger says, “A disadvantage that Will has is, I think, Austinites want an environmentalist to be leading the city at this time. I think that people realize that after six years of the ‘green’ council, our air quality is worse than ever and Barton Springs is in grave jeopardy.”

Nofziger says, “The council didn’t do enough to protect the environment and Barton Springs, and this latest round of publicity about the threat to Barton Springs illustrates that.” He contends that the city council made a “huge mistake” in not strengthening the Save Our Springs Ordinance after the Supreme Court ruled the city had the right to protect the people’s water.

Despite Nofziger’s record on environmental issues, environmental activists abandoned him in the 1997 campaign in favor of Kirk Watson, a situation Nofziger attributes to entering the race late. This time, Nofziger hopes for more loyalty from his former allies, and challenges them not to be complacent.

“This election is going to separate the real environmentalists from the lip-service environmentalists,” Nofziger says. “The environmentalists who have been content to sit back the last six years and watch the air get dirtier and watch Barton Springs become more and more threatened, they’re going to support Will Wynn. The real environmentalists who realize that we better do something or it’s going to be gone, those are the ones who are going to support me, because I’ve done something…Every big environmental issue over the last twenty-five years, I’ve been involved with.”

Nofziger claims to have played a key role in getting voter approval for building the Austin Convention Center, a move spearheaded by then-mayor Lee Cooke, and notes that the Convention Center makes money and boosts the economy. Nofziger wants some of the credit for getting the city’s airport moved to the former Bergstrom Air Force Base. He also notes that both the convention center and new airport were well managed projects that came in at or near the approved budget—in contrast to some of the current city construction projects like the new city hall, which is neither on time nor on budget.

In support of the music business, Nofziger says he played a role in forming the Austin Music Commission, starting the music industry loan program, and branding Austin as the live music capital of the world. Had he been on the current council, Nofziger says would have voted to continue funding for the Austin Music Network, although he faults the council for awarding contracts to operate the network without taking bids.

“If I’m the mayor I will wean the Austin Music Network within three years,” Nofziger says. First, it would be put out for bids, he said, and then other funding sources would be developed. Noting that music is a big attraction for Austin’s tourism industry, Nofziger says, “I’m going to make music a priority.”

Nofziger says if he was on the current council he would have voted for the resolution opposing war in Iraq.

Noting that Council Member Will Wynn cast the only vote to stop funding the Austin Music Network and abstained from voting on the anti-war resolution, Nofziger stretches the point, saying, “He’s against music and for war.” (For the record, Wynn says he abstained on the Iraq resolution because it’s a matter outside the council’s jurisdiction.) Don’t be surprised if you hear Nofziger on the campaign trail accusing Wynn of wanting to “Make War, Not Music.”

Like Wynn, Nofziger believes that Austin’s rules for financing council and mayoral campaigns are unsatisfactory. Nofziger advocates raising the $100 contribution limit to $500.

“My campaign is geared to increase voter turnout,” Nofziger says. He says the meaty issues facing the city ought to generate more interest, including the cost of living, the city’s spending, and the need to revitalize the economy, protect the environment, improve transportation, and keep Austin weird.

Nofziger criticizes the current council for giving the Convention Center Hotel project $15 million after the project’s backers had already agreed to build it without city assistance.

“Smart Growth was a disaster,” Nofziger says, noting the loss of such icons as Liberty Lunch, Ruta Maya, Steamboat, and Waterloo Brewery, not to mention the looming skeleton of the Intel building. If elected, Nofziger says he will move to stop giving incentives for development. “My approach will be on small business…the backbone of the Austin economy.”

If elected, Nofziger says he will seek to sit on Capital Metro’s board of directors, on which two council members now sit. “The twin issues of transportation and air quality are at such a crisis point in Austin that it demands the time and attention of the mayor.” He says that Capital Metro’s sales tax of one-percent should not be reduced but the money should not be stockpiled. Instead, it should be used to improve the mass transit system, reduce traffic congestion and improve air quality.

Regarding other transportation issues, Nofziger says that Governor Rick Perry’s strong support of State Highway 130 will move its construction forward. Nofziger thinks commuter rail makes more sense than light rail.

Nofziger’s own ideas for transportation are in a package called Affordable Clean Air Transit, improvements that would be cost-effective, minimize street interruptions for construction, and can happen quickly, he says. This would involve replacing “Capital Metro’s diesel fleet with smaller, cleaner, quieter buses, some battery powered, some turbine powered.” (Capital Metro is already pilot testing turbine-powered buses.)

“My approach to make Austin the center for clean vehicles…is for Capital Metro to offer a rebate of $5,000 to people who buy one of those (Toyota) Prius or Honda (Insight) vehicles that get better mileage. That would be a substantial enough amount of money to spark some interest…We should introduce to Austin clean vehicles and educate our populace that you can have a clean vehicle—you’re not limited to these gas-guzzling, exhaust-belching polluters.” Nofziger says he drives a small Chevrolet pickup truck.

On the subject of regional planning, Nofziger says, “We need to talk to our neighbors, obviously, and pursue a hospital district.” But he is wary of Envision Central Texas, a regional planning organization that Will Wynn helped to form. “Envision Central Texas is basically Phase One of the next light-rail campaign…I’m sure the result is going to be, ‘we need to build light rail.'” Nofziger says as mayor he wants to be part of the regional planning effort that Council Member Daryl Slusher has initiated with Hays County, which could lead to a blueprint on how to develop the Barton Creek watershed.

Nofziger plays up the fact he has lived in South Austin for nearly thirty years. “In trying to keep Austin, Austin, and recognizing that the true Austin is slipping away, we need a true Austin mayor. I embody that. What’s more ‘Austin’ than having a former flower seller who is a musician be the mayor of the Live Music Capital of the World, who also happens to have the most experience? That’s what keeps Austin weird—the weirdest guy has the most experience.”

Regarding Mayor Gus Garcia’s intention to further restrict smoking in public places, Nofziger says that while he does not smoke, “That’s not something I’m really going to push…I think the current situation is pretty good.”

To address the revenue shortfall in the city budget, Nofziger says, “There’s no escaping layoffs this time around. The city hired a lot of people the last several years, during the boom, and the city pegged its spending and hiring to the boom economy. And of course we have to adjust back as we’re in a bust now. We have to lay people off and there’s a substantial savings in that. And we have to stop hiring all these consultants…We’re going to have to get down to all the things we did in 1987 and 1988, which is (to cut) travel, magazine subscriptions, all those things. It’s going to be a real belt-tightening time.”

Because the city has incurred so much debt, Nofziger says it may not be possible to balance the budget without a tax increase, but that’s something he would study after taking office. If elected mayor, Nofziger says, “I am going to take a voluntary pay cut and reduce the mayor’s staff.”

On the subject of funding for women’s reproductive healthcare, Nofziger says he does not foresee reductions, “but we’ll look at all the funding that we do. We won’t start with a zero-based budget like the state is doing, but we’ve got to look at every place we can save some money.”

Nofziger thinks that the financial problems caused by the city paying for healthcare of people from surrounding counties is an issue that the federal government should help with. The city should continue to work with the Legislature to create a hospital district as well. “We have to have a regional approach to healthcare.”

In this election, we can count on Max Nofziger, who still sports the trademark “Buffalo Bill” facial hair that makes him instantly recognizable, to offer us a blast from the past about why he’s the best person for the job.

The man who carved a good life out of pastrami now wants to get a new life—as Austin’s top elected official.

The man who carved a good life out of pastrami now wants to get a new life—as Austin’s top elected official.

While Marc Katz’s unmistakable New York accent will be with him always, he has been an Austin resident for more than a quarter-century. He was born in Far Rockaway in the borough of Queens, and graduated from Manhattan’s rigorous Stuyvesant High School. His formal education ended when he dropped out of the University of Oklahoma. Back in New York, Katz grew unhappy with the expensive, crime-ridden city that had a sub-par educational system and incredibly high taxes. He says the crowning blow came when the New York Daily News headline blared, “New York Drop Dead,” which had been President Gerald Ford’s initial answer to the Big Apple’s request for a financial bailout. After the city itself raised taxes and cut spending, Ford relented, signing legislation extending $2.3 billion in short-term loans, enabling the city to avoid default. Katz nevertheless decided that Austin would be a far better place to raise his two children, daughter Andrea born 1969, and son Barry born 1971. He sold his eatery, Meyer’s Restaurant in Jackson Heights, and moved here in 1977. He was thirty years old.

Having been in the restaurant business all his life—indeed he was the fourth generation in a family of kosher butchers and deli owners—Katz nevertheless tried a new career in Austin, selling Ford automobiles for Bill McMorris. But when the restaurant property just down the street from the car dealership became available, he pounced on it, and In 1979 opened Katz’s Deli and Bar. Since then he’s made a name for himself running the place and advertising “Katz’s never kloses.” In time, he would add a nightclub upstairs and buy a couple of properties adjacent to the Sixth Street eatery. Together these three properties are now on the tax rolls for $2.3 million. Katz also has an ad agency, Synergy Associates, that handles advertising for the deli, other restaurants and a few other clients. His son Barry cloned the deli with a second restaurant in Houston.

The family’s business squabbles made newspaper headlines in late 2001, when Marc Katz sued, alleging his son was siphoning money out of the Austin eatery for the Houston operation. The legal wrangling ended last summer, leaving Barry with full ownership of the Houston operation and Marc likewise in possession of the Austin original, which he says today is grossing more than $4 million annually.

It was during this father-son dustup that Marc Katz’s former narcotics addiction came to light. Not that it was exactly a secret. Katz had already made a full confession, so to speak, on national television. In 1999 he was profiled on the PBS program Small Business School. In that interview, Katz said, “I was in rehabilitation for fourteen straight months, and it took every minute of it. And I think my life is going to be spent in rehabilitation now.” Katz says he completed rehabilitation programs in Maryland and Florida about a decade ago.

His “dark past” made running for public office a hard sell for Melanie, his fourth wife, Katz says. He claims that kind of past is shared by many others who are prominent in the community. “I am surrounded with people you know very, very well, you will recognize very, very well, who are also in recovery.” He says these supporters gave him the courage and the insight to admit his defect. “I have a tremendous opportunity here to set an example.”

One thing going for Katz in the mayoral contest is huge name recognition reaped from decades of heavy advertising, for which he says he spends about seven percent of gross revenue. Hence his claim that polls in recent years show he has “the most recognizable voice and face in Austin.”

That presents a challenge in its own right. “People say to me, ‘Are you really going to do this?’ That’s what we have to overcome…I’m really doing this not as a restaurant owner, I’m doing this as a citizen of Austin…I’m identified strongly with the restaurant, as it should be. However as mayor, I’m not the pastrami king.”

Katz says he has built a brand that people recognize and he believes that the City of Austin has done the same, but the city’s image has lost some of its luster.

“Since the high-tech bust, the Austin brand is hurting,” he says. “We need to raise the bar on the Austin brand. The people that live here need to have a better city to live in, so other people want to live here—that’s controlled growth—not incentives to corporations to move here. If your product is good enough, you don’t have to give incentives.”

Carrying the analogy between running a deli and running a city a step further, Katz says, “It’s simple enough to know what makes the product good enough; ask the taxpayer what do they want, rather than telling them what’s good for them. I don’t think the City of Austin has it’s ear to the people.”

Katz says the city is in financial trouble and he can help. “The way business handles debt and the way politicians handle debt are two different ways…We cut costs. We have urgency. The buck stops at us.” With the city, he says, “I believe the buck stops at the taxpayer,” thumping the table with a finger. “I don’t think the taxpayer, the citizen of Austin, is being represented properly from a financial standpoint.”

He claims he’s never laid off an employee due to hard times, and he doesn’t think that the city needs to, either, despite the budget crunch. But vacancies should not be filled and attrition should be used to trim expenses.

“Really the only thing we have to do right now is address the financial position of the city. We can’t afford the luxury of entertaining performing arts centers that say they’re going to come up with the money after we gave them the land, and then come up short and ask for bond money from elsewhere. We can’t afford consultants to tell us whether or not streets need to be two-ways…Although probably one of the three top issues we have is transportation and traffic, there’s nothing we can do about it right now anyway, until we get our money settled.

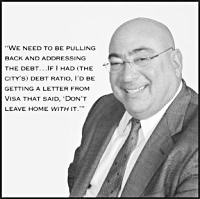

“We need to be pulling back and addressing the debt…If I had (the city’s) debt ratio, I’d be getting a letter from Visa that said, ‘Don’t leave home with it.'”

For Katz it’s a matter of priorities.

“We are addressing things that don’t matter, and it’s ironic to me that the city council has a stance on Iraq, while there’s potholes. And as (Statesman columnist John) Kelso said the other day, we broke the Guinness Book of Records for red cones on Barton Springs Road, not only the number but the length of time that they’ve been up. I don’t feel like I’m qualified or that I’m talking to the people of Austin about (Secretary of State) Colin Powell’s job. I’m talking about running the city…Our problem as a municipality is not Iraq.”

While acknowledging that the possible war with Iraq is hampering the local economy, Katz says, “We need to face our very specific, solvable problems and do nothing else. It’s going to be painful. We have to be dogmatic. And we have to use a tremendous amount of expertise that’s available to us.”

Underlining his intent to actually run for the mayor’s job—and not just treat the race as a way to further boost his restaurant’s visibility—Katz has hired veteran political consultant Peck Young of Emory Young & Associates. While the firm has in recent years focused on helping candidates elsewhere, it played a key role in local elections for many years. Katz’s campaign manager is James Cardona.

Claiming to have no original thoughts of his own, Katz says he would do for Austin what former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani did for Katz’s old home town. “He made New York an attractive place to be. He dressed it up. He raised the brand.” Katz says Giuliani created a strong, positive environment. “Right now, that’s the job that Austin needs, and I have the roadmap from Mayor Giuliani.”

Katz was not familiar with the Austin Fair Campaign Ordinance, which sets limits on contributions and expenditures for candidates who voluntarily abide by it, and would be deciding whether to comply. He said the decision would be based on how much money it will take to win the election and how his personal funds may be used to achieve that. He says he plans to run campaign ads on television.

Asked what issues he will stress in this campaign, Katz says, “We need to make Austin a better place to live, to make Austin viable, to make Austin grow, to make Austin progressive. We need to cut what Austin does to the essentials.” While he thinks that police, firefighters and EMS are already performing at a “very high level,” he wants to raise performance higher still.

“What does it take to make a better police department? I think the police know that. I need to talk to the police…I need to talk to the top brass. I need to talk to the guys on the street. I need to talk to the firefighters…I do know a better job could be done if those departments were given more of a say in how to run this thing. I’m not a cop. Neither was Giuliani, and he created the greatest police force New York’s ever seen.”

Katz is on record opposing Mayor Gus Garcia’s proposed ordinance to further restrict smoking in public places. “I don’t smoke,” Katz says. But in his own restaurant, he allows smoking when the law allows it, and has separate ventilation systems as required. “It’s really a much bigger issue to me than the smoking…The city does not need to get into supply-and-demand in a business. We need to set up a business environment that makes it attractive to do business…The market will bear what the people want.”

Katz agrees with the Tobacco-Free Austin Coalition, made up of organizations concerned with health matters, that second-hand smoke is harmful, but adds, “My job is not surgeon general of Austin…I have the right to run my business. You have the right to come in or not come in.”

He says he operates Katz’s Deli however need be to attract the most customers. “I have my life tied up on Sixth and Rio Grande,” he says, “the city council does not.” Katz says he employs one hundred twenty people in good times and eighty in bad times, using attrition to shrink the numbers when necessary. Small businesses, collectively, are the city’s largest employer, he says. “We don’t get tax incentives. We don’t want tax incentives. We want an environment where we can do business…The more money I take in, the more people I employ, the more taxes I pay, the better off the city is.”

Despite the city’s reported $60 million budget shortfall, Katz says, “I don’t think we need city layoffs.” He says that a temporary freeze on hiring should suffice if the business environment is enhanced.

“For example, we’re the ‘live music capital of the world,’ and now we have a sound ordinance about the amount of noise that can come out of a club. If you have a music district, you need to play music…If someone moves in downtown next to a nightclub, that’s what they’re going to expect.”

Katz praises the city’s building inspectors, yet calls the regulatory system a disaster. “It is so counterproductive that it hinders growth.” His argument is not with the inspectors but with a code that he feels is overly restrictive, beyond what’s needed for public safety.

“I think keeping Austin weird is great,” Katz says. “I think legislating to keep Austin weird is a contradiction in terms.” He says the way to do it is to strengthen existing businesses, not legislate to keep other businesses out.

“I could take the Austin Music Network off the air tomorrow, and the only people who would be affected are the talented people who work there,” Katz says. “The city keeps coming up with more and more money and throwing it into a well that has nothing to do with being the live music capital of the world.” Katz says this is symptomatic of what’s wrong. “Austin Music Network is a great luxury for Austin—not now. The council did nothing that I know of to promote Austin City Limits and it’s an international brand.”

Will a tax increase be necessary to balance the budget? No, says Katz. “I think we would be chasing more and more people out of Austin and hurting the economy for the people who stayed in.”

Katz voices perhaps the bluntest idea any politician has ever espoused to address traffic congestion: “Nothing. Nothing. The problem is so huge and so pressing and we don’t have a solution…Just to do something for the sake of doing it is not the answer,” he says, thumping the table again. “What’s needed is a comprehensive plan,” he says, “and on top of that, even if we had a solution today, we don’t have the money.”

Carpooling should be increased, Katz says. “(The) one man, one horse day has got to end.” Mass transportation is the solution to clean air in the long run, he says, and that should involve getting more people to ride the buses.

Katz says the city shouldn’t have paid $15 million to help build the Convention Center Hotel when it was not part of the original agreement. “A deal is a deal is a deal,” he says.

Katz opposes cutting Capital Metro’s sales taxes, but he says the agency should be run in a more businesslike manner. He said he was glad that light rail failed in the November 2000 referendum and conditions are not right to go forward with the project now.

The mayoral candidate says he has been to council meetings “embarrassingly infrequently; maybe I’ve been to five.” One that he recalls was a zoning case many years ago involving land he owned in South Austin. Nor does he watch council meetings on television. “They’re too long and they’re frustrating,” he says. So why would he want to preside over that? “I see a lot on the agenda that’s unnecessary,” he says. Pounding the table lightly, Katz says, “I think meetings like that need to be sharp and to the point.” He would eliminate “fanfare” such as music and proclamations. “We would just sit down and meet…If a council member wants to give someone recognition, he should do it on the council member’s time, not on council meeting time…I would cut the agenda and limit the amount of time we talk on each issue.”

Public forums where anybody and everybody is allowed to speak, Katz says, should not be held at council meetings. Instead a city council member or two can hold separate meetings on the issues and then brief fellow council members. “We’ve put together council meetings and town meetings under one roof. It makes (meetings) so long it’s counterproductive.”

Regarding protection of water quality, Katz says, “There may be issues as important, but I don’t know that there’s anything more important.”

He was not familiar with Smart Growth incentives the city has used to promote certain types of development. “I don’t know enough about it” he says, “but the general concept is not one which is attractive to me. If this is smart growth—what we’ve experienced in Austin the last few years—I need another label, ’cause I’m unimpressed with how smart we’re looking right now. I see half-finished buildings. I see farm land on Sixth and Lamar.”

Katz says municipal government overreaches. “I maintain as a general rule if you create the right environment—that’s smart growth. People will want to be here. When we’re ‘buying’ people to be here, that’s a whole ‘nother deal…If I make a better city for the people living here now…other people will come and go, ‘God, I want to live here,’ and that will be growth.”

He opposes incentives for development in general and particularly for development at Sixth and Lamar that might hurt existing businesses. But he adds that the city should not legislate against any particular business locating there. “The free market must prevail,” he says. “We are in a capitalistic system.”

Regarding women’s reproductive healthcare at Brackenridge Hospital, Katz says, “I don’t have enough information.” Nor does he know whether city funding for such healthcare might need to be reduced due to the city’s financial crunch.

In view of his past problems, is Katz up to the pressure that an Austin mayor faces? “I can’t imagine anybody being more capable to stand up to economic and political pressure. I’ve been trained for this my entire life. The restaurant industry is closer to WW II on a daily basis than anything else…I don’t see the city’s problems that different than any businesses’ problems.”

“Whoever is elected mayor on May 3,” Katz adds, “the primary goal needs to be ‘Austin never forecloses’—and we’re close.”

Brad Meltzer wants to be your next mayor, but don’t confuse this Brad Meltzer with the best-selling young novelist of the same name.

Brad Meltzer wants to be your next mayor, but don’t confuse this Brad Meltzer with the best-selling young novelist of the same name.

Bradley Charles Meltzer says he was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, and graduated from nearby Needham High School before earning a bachelor’s degree in accounting from Bentley College in Waltham, Massachusetts. Citing Austin’s quality of life as the main attraction, Meltzer says he left a management position with theatres and an ad agency in Boston and moved to Austin in 1987. From 1987 to 1992 he was executive vice president of Lexus Laboratories in Austin, a company that produced generic birth-control pills and a number of other pharmaceuticals. Today he owns and manages fifteen northeast Austin apartment complexes totaling more than six hundred fifty units, which he collectively calls Westheimer Apartments, plus Benihana Restaurant franchises in both Austin and San Antonio.

Although the forty-eight-year-old Meltzer has never before run for public office, he is serious about this campaign. That’s signified in part by the fact that he has established a campaign budget estimated at $150,000, he is willing to spend his own money in the campaign, and he has hired Ron Dusek, who for thirteen years was a spokesman for attorneys general of Texas, most recently for Democrat Dan Morales. The campaign manager is Carlos Espinoza. Meltzer’s daughter Lauren, twenty-two, and son David, eighteen, are both active in the campaign.

Meltzer was the first candidate to launch television commercials in this campaign. He has been running spots several times a day on KTBC Fox 7 since mid-February. But don’t expect to see him attacking his opponents.

“I’m sick and tired of seeing all this negative campaigning and how people are trying to destroy other people’s reputation,” he tells The Good Life. “I think it’s about time that we stopped, and I want to take a leadership role in that. I want to stop this negative campaigning and people-bashing…I want to show the nation that we don’t have to be bashing this candidate…and looking for their Achilles’ heel, hurting them, hurting their families, hurting their friends.”

No council-meeting junkie, Meltzer estimates that he has attended perhaps fifteen city council meetings in as many years, drawn by issues such as education and affordable housing.

In explaining why he thinks he’s best qualified to lead city government, Meltzer touts his diversified business experience and says the mayor’s job is analogous to the chief executive officer of a business.

“What I can offer is to take the lead as a successful businessman in very difficult businesses…I know how to put a budget together. I know how to negotiate. I know how to lead. And we’re now in a very tough fiscal time and I feel that with those kind of qualities I can do a success for the City of Austin.”

The city’s financial crunch is Meltzer’s foremost concern.

“My message is we’ve been taxed and taxed and taxed. I’ve never seen it since 1987 go down…What I’ve heard is that we’ve got an $80 million shortfall as far as taxes are concerned, so some difficult decisions are going to be made, and…I’d like to bring forth my leadership to take care of it.”

As an example of his leadership skills, Meltzer claims he was the first person to develop a direct-to-consumer marketing plan for a prescription drug (a generic birth-control pill, N.E.E. 1/35). With no previous experience in the pharmaceutical industry, he says, he won approval for the plan from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and convinced the American Medical Association. He says the program established a new paradigm for directly educating consumers, instead of the marketing drugs through doctors and pharmacists. Meltzer says his experience in marketing would work to the city’s advantage.

“The City of Austin is the best place to live in the United States,” Meltzer says, “and part of my campaign is to market the city more, to give more budget to the Austin Convention and Visitors Bureau.” As a private citizen, Meltzer says he has participated in a panel discussion with the Bureau regarding the Greater Austin Tourist and Entertainment Guide, a magazine that Meltzer supports by purchasing paid advertising for his Benihana Restaurant.

Meltzer is a member of the Mayor’s Affordable Housing Committee established after Gus Garcia was elected mayor. The group is chaired by Mayor Pro Tem Jackie Goodman, and operates less formally than the city’s boards and commissions. Meltzer defines affordable housing as a good, safe place for low-income people to live. To increase availability, Meltzer says he wants the city to provide affordable loans to support profit-making companies that provide affordable housing, so they can keep their properties in good shape. The overriding goal is for low-income people to be able to afford to stay in Austin and not move outside the city. At present, Meltzer says, “We have plenty of affordable housing as far as apartments are concerned, because we have overbuilt.”

Two of Meltzer’s own apartment complexes, totaling one hundred sixty units, were rehabilitated with money from a city loan. He says he borrowed $500,000 in 1991 on a fifteen-year note and repaid it in only five years, a claim substantiated by Paul Hilgers, the city’s Community Development Officer.

Meltzer opposes any change to the city’s no-smoking ordinance. “I’m opposed to it because I want Austin to be a successful city for business. What this ordinance is trying to do is control and inhibit its businesses…I don’t think we need to burden the consumer. I don’t think we need to burden the businessman by hurting him, because of the fact he can’t have in his bar someone who wants to smoke and drink.” Meltzer says his own restaurants in Austin and San Antonio are non-smoking facilities, but adds, “I want as an entrepreneur to be able to make the decision, not as the mayor to make that decision.” He says if the people of Austin want smoking to be further restricted, then citizens should be bring a petition to be put on the ballot; it should not be put on the ballot by the city council.

In a similar vein, Meltzer says, “If we show people outside the community that the City of Austin is very business-friendly, I think that would attract other businesses to come into Austin to fill up this gap of all these empty apartments, empty office buildings, empty industrial buildings, and increase our tax base.”

As a current member of the Lieutenant Governor’s Business Advisory Board, Meltzer says he will learn from the state’s recent initiative with zero-based budgeting, and use that knowledge to improve the city’s budgeting methods.

A photograph of Meltzer and his campaign treasurer, Frank Ivy Jr., appeared in the Austin American-Statesman‘s coverage of Governor Rick Perry’s inaugural ball. Both men were courting support among the revelers by wearing “Meltzer for Mayor” buttons. It was no accident that Meltzer was celebrating the Republican Party’s second straight sweep for statewide offices, as he has been a steady contributor to GOP causes. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, between August 1999 and February 2003, Meltzer donated more than $8,000 to the National Republican Congressional Committee, a figure that Meltzer confirms.

Meltzer says he is also on the Citizens Task Force of U.S. House Speaker J. Dennis Hastert (R-Illinois) which advises the speaker on entrepreneurial and tax issues. He says he received the National Leadership Award last October from the Republican National Committee for suggestions he has made on a wide range of tax issues, and for traveling to Washington to participate in meetings several times a year since 1998.

On the local political scene, Meltzer says he has contributed to Mayor Gus Garcia and Council Members Betty Dunkerley and Raul Alvarez. “I believe in the political processes and I believe that (candidates) need to be funded,” he says.

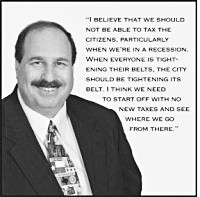

Meltzer opposes a tax increase to balance the city’s budget. “I believe that we should not be able to tax the citizens, particularly when we’re in a recession. When everyone is tightening their belts, the city should be tightening its belt. I think we need to start off with no new taxes and see where we go from there.” Asked if jobs might be cut from the budget, not just vacant positions, Meltzer replies, “Everything is on the table.”

One of Meltzer’s more controversial ideas is to give a property tax break of “ten-to-fifteen percent” to city employees, as an incentive for them to live in Austin. “While they live in the city they would be going to the grocery stores…churches…schools (and) restaurants.” Asked why other property taxpayers should carry the burden of paying higher taxes to make up the revenue lost through this benefit for city employees, Meltzer says the loss would be offset by the higher sales taxes the employees would pay shopping in Austin. “I think we’ll get more than the money back,” he says.

On the topic of traffic congestion, Meltzer says the city needs to better coordinate road and lane closures necessitated by construction projects, such as sewer repairs and cable installation, and to better synchronize traffic lights in areas such as Congress Avenue downtown.

On the community service front, since 1997 Meltzer has been a member of the American Red Cross board of directors for the Austin area, and he currently chairs the committee on disaster fund-raising. In that role he has responded to fires to assist displaced residents, using Red Cross funds to pay for such things as clothing, furniture and deposits. He has housed dozens of disaster victims in his own apartments, he says.

Meltzer says he opposed the light-rail initiative that voters narrowly rejected in 2000 and would need to hear “convincing arguments” to support it in the future. He says he would like to explore the possibility of monorail, such as the project being built in Las Vegas. (That project is scheduled to start carrying passengers over a four-mile route adjacent to the Las Vegas strip in 2004; it is privately funded, with revenue bonds tied to farebox and advertising revenue, according to www.lvmonorail.com.)

Regarding air quality, Meltzer says, “I encourage people to use smaller vehicles and I’ve taken a leadership role and started using cars that (give) more miles per gallon.” Asked to amplify, Meltzer adds, “Instead of buying the big Cadillac Escalade, which is beautiful, I bought a car that has high mileage, a Chrysler Concorde.” (For the record, the Chrysler Concorde is rated at nineteen miles per gallon city, twenty-seven mpg highway, according to www.autobytel.com. While not exactly miserly, the Concorde’s not quite as thirsty as the Cadillac Escalade, a sports utility vehicle rated at fourteen mpg city, eighteen mpg highway. For comparison, Mayor Gus Garcia purchased a Toyota Prius rated at fifty-two mpg city, forty-five mpg highway.) Meltzer supports Ozone Action Days and would like to see heavier promotion of the free bus fares on those days.

Meltzer was not aware of the Smart Growth incentives that have been given primarily for downtown development projects. “I have to get educated,” he says.

Regarding the Austin Music Network, Meltzer says it should be marketed to make money instead of losing it.

Asked if he would seek support of environmental groups, Meltzer says, “I’m looking to seek the support of everybody who has the same mission I have, which is to make the government run like a successful business, but I’m not looking to hurt our environment. I want our environment to be here for our children, our grandchildren and our great-grandchildren.” And as for courting environmentalists? “I’m going to discuss my issues and discuss their issues and see if we have common ground for them to support me.”

Asked for his views on women’s reproductive healthcare at Brackenridge Hospital, Meltzer says, “I have no comment about it, because I really haven’t thought about it.” In view of the city’s budget crunch, does he foresee any reduction in city funding for women’s reproductive healthcare? “I have to look at every line item and discuss them with my fellow council people…

“I don’t know all the issues,” Meltzer adds. “I know what the major issue is right now and that is budget deficit. We cannot print money here and we can’t magically get it from the state because they have a huge budget deficit.”

Summing up the key issues that he will campaign on, Meltzer named ensuring no new taxes, reducing traffic congestion, supporting public safety, making Austin business-friendly, and providing affordable housing.

These articles were originally published in The Good Life magazine in March 2003

Historical footnote: The detailed results of the May 3, 2003, mayoral election are posted on the City of Austin’s election history web page. The four candidates profiled here netted:

Will Wynn: Won the election with 58.26% of the votes

Max Nofziger: Placed second with 15.97%

Mark Katz: Placed third with 13.16%

Brad Meltzer: Placed fourth with 8.26%