About 11,200 words

About 11,200 words

“There ought to be a natural coalition between environmentalists and defense groups. Environmentalists want to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. Defense groups want to limit our vulnerability to oil cutoffs or blackmail. A common denominator is the need to control cars’ gasoline use.”

A man deprived of sustenance will die of thirst long before he will succumb to starvation, notes author Desmond Morris. But, we ask, how long can a human being survive without air? Only moments, to be sure, for air is the essence of life. What concerns us here is not how long we can hold our breath, but how long can we live, and what suffering we must endure, if forced to breathe polluted air? Not that we want to be human guinea pigs to find out, but given the increasingly marginal nature of air quality, what choice do we have?

Central Texas has very few smokestack industries but our air is far from clean. Much of our air pollution blows in on the prevailing winds from the Houston area, which recently attained the dubious distinction of having the worst air quality in the nation. Our own area’s single largest contribution to air pollution, say local experts, is what comes out of the tailpipes of our motor vehicles which, according to the Texas Department of Transportation, number 1.3 million within the five-county area. Nearly 900,000 of those are registered in Travis County, while Williamson County adds 237,000 and Hays County another 88,000.

Central Texas residents not only own a lot of vehicles but they want to use them every time they step out the door. Given the way that our communities are designed, particularly the suburbs, many people have little choice but to drive for the necessities of life. Austin-based NuStats Market Research in July 2001 surveyed some 200 respondents in five Central Texas counties, and found that, “Central Texans love their cars. In fact, nearly two-thirds (sixty-two percent) of respondents drive to work or school alone.”

Austin Mayor Gus Garcia says commuters are contributing to our air pollution but most don’t realize it. “People still think they can drive a hundred miles into town and back in their Suburbans or one-and-a-half-ton trucks and they’re not affecting air quality,” Garcia says. “I’ve got news for them—they are affecting air quality.”

Whether imported or homegrown, the air-quality monitors in the Austin area measure pollution without regard to point of origin. When the readings are too high, that’s bad news.

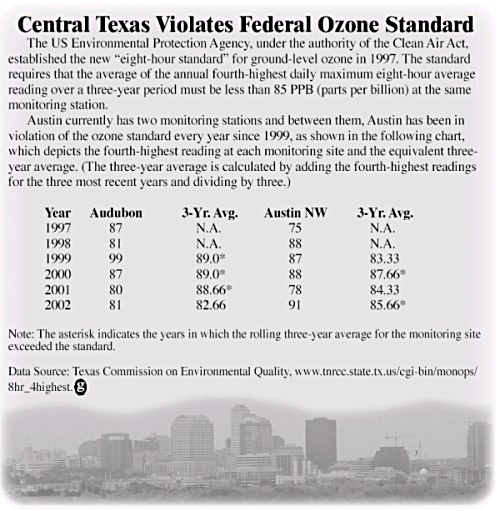

Bad news is what we got September 14, 2002. That was a bad-air day. That was when, for the fourth time this year, the air quality in Central Texas exceeded the amount of ground-level ozone pollution allowed by the federal Clean Air Act. That event, when combined with monitored levels of ozone pollution for 2000 and 2001, put this area in violation of the Clean Air Act. In fact, the Austin area has been in violation of the ozone standard every year since 1999 (see above chart, “Central Texas Violates Federal Ozone Standard”). If we had enjoyed a better year in 2002, ozone-wise, the Austin area might have limboed under the regulatory bar and no longer have been in violation. No such luck.

This is bad news for public health, because it means that all of us—healthy adults, susceptible young children, and people with chronic respiratory problems—are breathing air that is unhealthy and can make us sick. (See accompanying story, below, “Ozone and Your Health.”)

Violating the Clean Air Act is also bad news for our already slumping economy, because it means that, sooner or later, we will be forced by federal and state regulators to clean up the sources of emissions that contribute to ground-level ozone. The uncertainty as to when such action will be mandated—and the reasons why the problem is not being addressed adequately by the federal government—stem from an ongoing lack of support from Congress, active opposition by the Bush administration, and litigation.

The Congress—The lack of support from Congress is typified by the absolute ban that federal lawmakers have imposed for the last six years on the US Department of Transportation, preventing regulators from requiring automakers to make cars that get better gas mileage and produce fewer tailpipe emissions. This is not only bad for the environment but bad for our nation, which is far too dependent upon imported oil. US Representative Lloyd Doggett (D-Austin) says, “As current events in the Middle East remind us, the creation of more fuel-efficient cars is not just a matter of securing a healthy environment, it is a matter of national security. Unfortunately, our current leadership has provided nothing but excuses and showed that it is unwilling to hold the industry accountable.” Or, as Senior Editor Gregg Easterbrook put it in a June 2001 editorial in The New Republic, “The worst thing about the Bush plan is its silence on the primary energy-efficiency question of the moment: the need for higher gasoline mileage across the board—not in a few hybrids but in the cars, SUVs, and light trucks everyone drives.”

The President—The Bush administration’s disdain for air quality is exemplified by its plan to roll back the “New Source Review” process for power plants, oil refineries. and other industrial facilities in a way that environmental groups and others contend would result in higher emissions. “Pollution from refineries and power plants threatens our environment and the health of every Central Texan,” Representative Doggett says. “Weakening the Clean Air Act would reverse the progress made over the last thirty years against air pollution and global warming.” The American Lung Association, it its report titled State of the Air: 2002, declares, “Rolling back the New Source Review protections would be the greatest attempt to weaken the Clean Air Act since its inception.”

The Litigation—A lawsuit brought by the American Trucking Associations Inc. and others attempted to prevent the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from implementing new standards for ground-level ozone (smog) and particulate matter (soot)—standards that would better protect the public health, as required by the Clean Air Act. In February 2001, the US Supreme Court upheld the new standards but ordered the EPA to develop a reasonable approach to implementing the new ozone standard. The EPA was devising a final rule on the implementation strategy before it designates areas that are in violation of the ozone standard. To that end, the EPA had been holding public hearings around the country when in June 2002, the American Lung Association, Environmental Defense, Natural Resources Defense Council, Sierra Club, and five other environmental groups filed notice of intent to sue the EPA unless the agency designated the Austin area and 107 other metropolitan areas in violation of the ozone standards.

Negotiations are underway at the national level to resolve the issues before the lawsuit is filed, says Janice Nolen, national policy director for the American Lung Association. What’s being sought, she says, are “enforceable dates for the EPA to actually designate nonattainment areas as required under the Clean Air Act.”

Jim Marston of Austin, director of the Texas regional office of Environmental Defense (formerly Environmental Defense Fund), has been involved in the negotiations as well. “I think it’s likely we’ll have an agreement to have designations (of nonattainment areas) sometime in 2004,” Marston says.

Austin leaders long ago recognized the hardships we would face if declared a nonattainment area. All they had to do was observe what was happening in the air-quality regions of Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston-Galveston-Brazoria, Beaumont-Port Arthur, and El Paso, which were long ago declared by the EPA to be in nonattainment. Nonattainment puts a severe hamper on economic activity, as in Houston, for example, by lowering speed limits, requiring the testing of motor vehicles for tailpipe emissions, and requiring petrochemical plants to vastly reduce emissions. New industries tend to steer clear of nonattainment areas because these kinds of mandates make it harder to do business and add extra expense.

The Austin area, along with four other air-quality regions in the state, is classified as a “near-nonattainment area,” indicating that while Austin had not been officially designated as being in violation of the Clean Air Act, it is very close.

It is against the backdrop of impending federal mandates that the Austin area has been working to improve air quality. The effort began at the urging of Kirk Watson while he still chaired the Texas Air Control Board (an agency that was later folded into the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission, which recently changed its name to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality). Representatives from several area organizations formed Clean Air Metro Austin in 1993. In 1995, that group became the Clean Air Force and incorporated as a 501(3)(c) nonprofit organization. In 1996, the organization was renamed the Clean Air Force of Central Texas to reflect the regional nature of air-quality issues.

In August 2000, as chair of the Clean Air Force, Austin Mayor Kirk Watson assembled a committee of elected officials, including the county judges of Travis, Williamson, Hays, Bastrop and Caldwell counties, and mayors of Round Rock and San Marcos. These officials began meeting as the Clean Air Coalition of Central Texas. By 2002, the group had expanded to include the mayors of Bastrop, Elgin, Lockhart and Luling, as well as State Senator Gonzalo Barrientos (D-Austin). Watson’s tour ended when he resigned as mayor of Austin to run for state attorney general.

The roles of the Clean Air Force and Clean Air Coalition overlap to some degree, even to the extent that both groups are chaired by Williamson County Commissioner Mike Heiligenstein. Some time ago, during Mayor Watson’s tenure, the two employees who staff the Clean Air Force were put under the wing of the Capital Area Planning Council (CAPCO), and Clean Air Force Executive Director Wade Thomason was required to report to the CAPCO’s executive director, despite the fact that he was supposed to be working directly for the Clean Air Force board of directors. Thomason was terminated August 1 by CAPCO’s executive director, and without a meeting of the Clean Air Force board of directors, according to Thomason. Jim Marston of Environmental Defense—who is on the Clean Air Force board’s executive committee—sent an e-mail to other Clean Air Force board members over the matter, pointing out that Thomason was fired without warning, without a meaningful evaluation process, and in violation of the Clean Air Force by-laws, which indicate that no one board member—including the chair—has the power to act on matters without the involvement and approval of the rest of the board. Marston’s e-mail indicates that he and some other board members “were not consulted about such a decision.”

Thomason says he’s not bitter about the way things ended but says that he was never given clear direction about what he should be doing to earn his salary of $58,000 a year. Thomason and others say that the role of the Clean Air Force began to blur when the Clean Air Coalition was formed, and the power naturally gravitated toward the Coalition, which is made up entirely of elected officials. Heiligenstein says action is underway to “define the roles of the Clean Air Force and the Clean Air Coalition so there’s no confusion anymore.” The Clean Air Coalition will deal with public policy, and the Clean Air Force will focus on public education, he says.

While the fate of one employee does not generally make or break the success of an organization, the way in which Thomason’s termination was carried out does raise a red flag about the way the Clean Air Force and Clean Air Coalition are managed, and particularly calls into question the idea of whether the next executive director should be forced to operate under CAPCO’s supervision.

Regional cooperation achieved

The Clean Air Force has done much to educate the public about air quality issues, but ultimately it is our elected officials who must make the decisions that will bring action. To that end, on March 28, 2002, the Clean Air Coalition, the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission, and EPA signed off on the O3 Flex Agreement for the Austin-San Marcos Metropolitan Statistical Area (O3 being the chemical symbol for ozone). The O3 Flex Agreement is a voluntary local approach to encourage emission reductions that will keep an area in attainment of the one-hour ozone standard (under which ozone may not exceed 0.125 parts per billion, or PPB, more than three times in three consecutive years at the same monitoring site), while also working toward the health benefits envisioned under the eight-hour standard (under which the average of the annual fourth-highest daily maximum eight-hour average reading over a three-year period must be less than 85 PPB). An area may be in violation for either one or both standards, depending on its air quality. (For more on the ozone standards, see accompanying story, below, “Ozone and the Law.”)

In one sense, the O3 Flex Agreement is nearly meaningless, as it only protects the area from being designated for exceeding the one-hour ozone standard; the voluntary actions it promises to undertake will achieve only a small fraction of the emission-reductions needed to comply with the eight-hour standard. Austin has never exceeded the one-hour standard, although it could do so at some point. The overriding value of the O3 Flex Agreement is that it marks the first time that Central Texas governments have cooperated on such a wide scale concerning an environmental issue. That’s in marked contrast to the lack of regional cooperation that has for so long hindered protection of water quality in the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer, as reported in The Good Life‘s cover story of July 2002 (“The Life and Death of Barton Springs.”)

The Texas Legislature has been of enormous help in addressing air quality issues by providing $10.3 million in funding since 1996, spread among Austin and the four other near-nonattainment areas (Corpus Christi, San Antonio, Tyler-Longview-Marshall, and Victoria). Nearly half of the total funding was provided in the budget biennium for 2002-2003. The Austin area was allocated $979,000 for 2002-2003 for planning and public outreach. “Without that money, this voluntary planning would not have been possible,” says Kate Williams, coordinator for the State Implementation Plan, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (formerly the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission).

The Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce has been a key player in trying to improve air quality by spearheading Clean Air Partners, an initiative to get businesses to voluntarily reduce emissions—especially emissions related to employee commuting. The Clean Air Partners program is especially notable when considering that in other Texas air-quality regions, business groups are usually in the forefront of the fight against efforts to improve air quality.

The Greater Austin Chamber’s work draws praise from Kate Williams, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. “They have been extraordinarily proactive for a chamber of commerce group in facilitating voluntary reductions,” Williams says. “That’s not normally what you’ll see from a chamber of commerce; you usually see the opposite—resisting.” In Houston, no fewer than eleven lawsuits have been filed to challenge the cleanup rules, ten of them by businesses or business groups, according to GHASP, the Galveston-Houston Association for Smog Prevention. Such lawsuits are common not just in Houston, Williams says. “Many areas react with fear instead of being proactive.”

In the fall of 2000, six major Austin employers—Advanced Micro Devices Inc., Intel Corporation, Motorola Inc., Samsung Austin Semiconductor, Solectron Corporation, and Vignette Corporation—agreed to become charter members of the Clean Air Partners program. These companies developed strategies and signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Clean Air Force to reduce, over a three-year period, employee vehicle-miles traveled by ten percent, or make equivalent emission reductions.

Not many other partners signed up until early this year, when on-line tools were established to provide information and a way to enroll. To date, twenty-four additional companies have joined the original half-dozen charter members as Clean Air Partners.

Rob D’Amico of Transportation Management Group, coordinator for Clean Air Partners, estimates that the thirty businesses now enrolled employ about 23,000 people. Other major companies, he says, “are right on the cusp of signing up,” and are inventorying their emissions and deciding how best to reduce emissions.

While it is certainly commendable that thirty companies are participating, that’s just fifteen percent of the 200 companies that the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce committed to get signed up from among its own members.

David Balfour, senior vice president of URS Corporation (formerly Radian International) is the volunteer who heads up the Clean Air Partners program for the Greater Austin Chamber. He says hard times are hampering progress. “With the economy like it is, businesses are hunkered down and trying to keep the business on track. It’s hard to take time to do something that has nothing in the world to do with their company.”

Jim Marston of Environmental Defense says the Clean Air Partners program, which his organization helped to start, is “going okay, but not great.” He says, “In economic tough times, things like air pollution are put on the back burner. It’s hard to get in to see business executives.”

Balfour says businesses tend not to understand the important role they play in air pollution: “They say, ‘I don’t have a smokestack; I’m not contributing to the problem.” But, he notes, “Austin’s problem stems from employees who get in their cars and drive to work. Although that’s not the only problem, that’s how most Austin businesses contribute to air quality problems.”

Once employers grasp this fact, Balfour says, they can usually find avenues to do things differently and address the problem of air pollution in a way that makes sense for their business. (See accompanying story, below, “We Can Reduce Ozone Pollution.”)

The extent to which emissions have been reduced by Clean Air Partners is being compiled for the first semi-annual report, which is due to be published this month. Balfour will be looking for ways to recognize achievements by Clean Air Partners, and to identify and help any companies who signed up but have not reduced emissions. “We want to recognize participation,” he says, “not who signed up.”

Being careful to reward only valid achievements is also the goal of Environmental Defense. “Companies are trying to get vindication or praise as part of their program and if that doesn’t happen, some companies are not excited,” Marston says. “Some companies want to be able to advertise that they are being noted by environmental groups as a leader. Groups like Environmental Defense give out praise when we’re certain they are doing something we can praise.”

In fairness, Marston points out that the Clean Air Partners program is the “first of its kind” and, for a program without a successful model to follow, it is understandably slow in building momentum. Which is why efforts are going to be redoubled.

Clean Air Partners has been assisted by the Austin Idea Network, a group of high-tech entrepreneurs who have raised money, developed the web site, and furnished volunteers to help recruit other businesses to join Clean Air Partners.

Capital Metro has done a tremendous amount to improve air quality in the Austin area. First and foremost, it provides a proven means of reducing pollution by getting people out of automobiles. For the year ending September 30, 2002, the agency estimated it had transported riders for a total of 32.2 million trips. Of that number, 24.6 million trips involved regular bus service over fixed routes and another 6.7 million trips were aboard the university shuttle. Capital Metro’s paratransit service carried passengers for 500,000 trips, and its vanpool service accounted for another 300,000 trips.

On Ozone Action Days, those days for which the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality forecasts weather conditions and traffic are likely to generate too-high amounts of ozone, Capital Metro provides free bus rides all day, which typically increases ridership about ten percent.

Capital Metro’s buses run on diesel fuel, the standard varieties of which produce high emissions of sulfur, particulate matter (soot), and nitrogen oxides, the latter being a contributor to formation of ground-level ozone. But Capital Metro’s entire fleet is powered by Koch Performance Gold Diesel. This cleaner-burning fuel reduces particulate matter and ozone-forming emissions by fifteen percent to twenty percent, compared to standard diesel fuel. Capital Metro estimates that if every diesel truck in Texas burned Performance Gold Diesel, from a pollution standpoint it would be the equivalent of removing 20,000 trucks from the road. In addition, Capital Metro is working with counterparts in Dallas, Houston and San Antonio to obtain Ultra-Low Sulfur Diesel fuel that would produce emissions, according to Capital Metro President and Chief Executive Officer Fred Gilliam, “almost equivalent to natural gas.”

Capital Metro will soon take delivery of six new hybrid buses manufactured by Advanced Vehicle Systems and plans to put them in operation before the end of the year. These twenty-two-foot buses are powered by a turbine diesel engine that provides power to electric batteries that propel the vehicle. Emissions are about a tenth of the 2003 standard allowed for diesel bus engines. In addition, Gilliam says Capital Metro expects to take delivery of a couple of forty-foot hybrid buses in the spring. And the agency is working with a bus manufacturer to explore the feasibility of retrofitting existing buses.

The light rail plan that Capital Metro had devised was narrowly defeated by voters in November 2000. From an air-quality perspective, that was a major blow to long-term plans for reducing dependence upon emission-spewing automobiles. Gilliam, who was named president and chief executive officer April 29, 2002, says the board of directors decided not to hold another referendum on light rail this year. Work is currently underway to develop a more comprehensive plan that also examines bus rapid transit, park-and-ride locations, neighborhood centers and more bus service. “We are certainly going to involve the community in the process and be sure we have support,” Gilliam says. “We’re trying to make sure we get everyone involved.” He says the new comprehensive plan should be completed “no later than early 2004.” That would provide plenty of time to hold a referendum in November 2004, should the Capital Metro board vote to do so.

While light rail is on the back burner and a new comprehensive plan is in the making, Capital Metro is allocating twenty-five percent of the sales taxes it collects to local governments. Most of that money is being spent for roads, Gilliam says. He hopes the next session of the Texas Legislature, which starts in January 2003, will not derail plans by coming after Capital Metro’s sales tax. “We’re continuing to work with everyone in office and aspire to be given their trust and respect,” Gilliam says. “This would be the wrong time to change the structure. Air-quality problems and congestion will not go away.”

The bottom line for Capital Metro, Gilliam says, is “We’re committed to do everything we can to produce pollution-free service.”

The City of Austin has been a leader in implementing ways to reduce ozone pollution. The Ozone Reduction Strategies Status Report published in February 2002 details a wide array of actions the city has taken to reduce emissions that contribute to ground-level ozone. The city’s overarching goal is to lower emissions of nitrogen oxide (NOx), one of the two primary precursors of ozone. (For more about ozone and precursors, see accompanying story, below, “Ozone and the Law.”)

The report notes that to bring the Austin area’s air quality into compliance with the eight-hour standard for ozone, “…many area organizations—particularly large employers—will need to adopt these strategies. It is the cumulative impact that will return ground-level ozone to healthful concentrations in this region.” Fred Blood, the city’s sustainability officer and primary author of the Status Report, says, “We have made baby steps in that direction, mostly through the Clean Air Partners.”

It will take a great deal more action than was committed to in the O3 Flex Agreement to comply with the eight-hour standard. The Austin area must reduce emissions by twenty to thirty tons, Blood says, and the O3 Flex Agreement-if carried out-will reduce emissions only by three to four tons. “The fact that we’re doing anything when not required by law is great, but we need to do ten times more.”

The actions carried out by the City of Austin are far too voluminous to list here, as there are ten strategies and within each strategy there are multiple initiatives under way, but a sample indicates what’s possible: One strategy is to voluntarily reduce vehicle trips taken by employees through telecommuting, compressed work weeks, promoting the use of carpools and vanpools, improving facilities for bicyclists and walkers, and providing incentives for employees willing to forgo a parking space. These measures are estimated to have saved five million vehicle miles annually.

Another strategy is to reduce emissions from fleet vehicles. The city operates four city-owned propane stations and has almost a thousand vehicles equipped to run on propane—which they do about eighty percent of the time, Blood says. That’s particularly noteworthy, he says, when considering that some fleet operators have skirted the intent of EPA standards by equipping vehicles to run on alternate fuels but not actually using alternate fuels.

Because of the particularly high emissions spewed out by diesel trucks, Blood says they are his “number-one enemy,” but private businesses using those vehicles can do better. “H.E.B. Grocery Company is one of my heroes,” Blood says, noting the work that our area’s dominant grocery chain is doing to improve its fleet.

Kate Brown, H.E.B.’s public affairs director for the Austin area, says twenty-two of the company’s seventy diesels operating in the Houston area run on liquefied natural gas (LNG) about ninety percent of the time, and on diesel the rest of the time. Houston was picked for this experiment because it has the worst air quality in any of the grocer’s Texas markets, and because it has sufficient LNG refueling stations. “It cost $32,000 per vehicle to make the conversion,” Brown says. So far, she says, “LNG vehicles have not been as good as the rest of the fleet,” but H.E.B. mechanics are working through the issues and improvements have been made. “It’s definitely the right thing to do for the environment,” Brown says. To expand the program into other markets, she adds, “It must also be good for the business.”

One simple measure that can go a long way to reduce tailpipe emissions is to cut the amount of time vehicles spend idling. This may be achieved by keeping traffic moving, which is top priority for the city’s program for synchronizing traffic lights, and by discouraging idling at places like drive-through restaurants. The city prohibits idling for more than five minutes at its own loading docks, Blood says, and there is a “high probability the city could pass a citywide ordinance” to address this opportunity for reducing emissions.

As the owner of power plants, the City of Austin has done much to reduce emissions from power generation. The Holly Power Plant and Decker Power Plant are older plants within the city limits, and Holly, located in the East Austin barrio, has drawn ongoing criticism from nearby residents concerned about safety and noise. When it comes to emissions, however, a report prepared in 1999 by John Villanacci, co-director of the Environmental Epidemiology and Environmental Division for the Texas Department of Health, stated that “when natural gas is used as fuel, the predicted ambient air quality impacts are such that they would not pose a threat to public health.”

Ed Clark, communications director for Austin Energy, says, “Holly and Decker are two of the cleanest plants in Texas for their age.” Clark says these plants produce about 1,700 tons of nitrogen oxide per year, compared to about 33,000 tons a year produced by on-road and off-road vehicles. The Holly plant has not used fuel oil for about a decade, he says, and Decker used it only for a couple of weeks when natural gas prices spiked.

The South Texas Project, a nuclear facility in Bay City, Matagorda County, produces few if any emissions that contribute to ozone pollution.

The city’s new Sand Hill Power Plant, which came on line last year in Del Valle, is a natural gas plant with low emissions that only runs during periods of peak demand.

The City of Austin and the Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA), deserve considerable recognition as co-owners of Fayette Power Plant, located in Fayette County, and managed by the LCRA. Although the Fayette generators burn coal, a leading source of air pollution, Ken Manning, the LCRA’s manager of environmental policy, says, “We will spend a total of $130 million to reduce emissions at this facility.” Only $30 million of that was mandated by a Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (now Texas Commission on Environmental Quality) under a rule that requires all old plants to cut nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions by half, Manning says. The extra $100 million investment to equip Units 1 and 2 with sulfur dioxide scrubbers is strictly voluntary. “Ultimately this flies in the face of the Bush administration efforts to back off on New Source Review,” Manning says.

Austin-Bergstrom International Airport was designed to reduce emissions associated with commercial aircraft operations. High-speed exits move aircraft swiftly from runway to gate, burning less fuel. All passenger-loading bridges at the airport terminal supply power, potable water, and air conditioning to docked airplanes. This eliminates supply vehicles and two large diesel engines that would otherwise be needed for power and air conditioning at each gate, and prevents an estimated 200 tons a year of emissions. In addition, the airport utilizes propane-powered buses to shuttle travelers and employees from the parking lot to the terminal.

How to clean our air

The good news is that all these actions have already been taken to reduce the pollution that plagues our skies. The bad news is we have so very far to go before Central Texas meets the eight-hour standard for ozone, and area residents can breathe healthier air. We can’t really clean our air but can only act to pollute less.

Our options are pretty straightforward, actually:

We could pray that good weather in future years will magically reduce ozone concentrations so that we don’t continue to violate the standards. In other words, we hope for a deus ex machina solution, for the hand of God to intervene and resolve our problems. Fat chance.

We could hope that the Bush administration succeeds in rolling back environmental protection so we’re not forced to clean up the air. That would call off the regulatory dogs—but it would not keep us from sucking up unhealthy air that is ruining our health and the health of our children, and prematurely killing people with chronic breathing problems.

Or we can realize that after four straight years of violating the eight-hour ozone standard, we must take action to drastically reduce the pollution we have been so blithely spewing skyward. Under this scenario, we can either wait until the litigation is resolved, the EPA issues its final rule, and officially designates the Austin region as a nonattainment area—probably sometime in 2004—or we can join a brand-new program called the “Early Action Compact.”

The Early Action Compact is a program under which voluntary Early Action Plans can be developed through an agreement between local, state, and EPA officials for areas that are in attainment for the one-hour ozone standard but approach or monitor exceedances of the eight-hour standard. The Austin area meets those prerequisites. Early Action Plans must include all necessary elements of a comprehensive air-quality plan, but will be tailored to local needs and are driven by local decisions.

The Early Action Compact offers some big carrots for participation: As long as the milestones are being met, then the area will not be designated as a non-attainment area for the eight-hour ozone standard. That’s especially important when you realize that the federal government can withhold funds for road improvements in nonattainment areas.

The Early Action Compact allows a locally designed plan that fits the area’s needs to go forward, once approved by the state and EPA, and not force the area into the cookie-cutter approach that would otherwise be mandated. Hence, local officials retain great flexibility as long as the Early Action Plan is being properly implemented. “Instead of ‘Thou Shalt Do This,’ local people get to choose,” says Kate Williams of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. “Being able to retain control at the local level is an extraordinary amount of power never seen in a State Implementation Plan process.”

San Antonio, which like Austin is a near-nonattainment area for violation of the eight-hour ozone standard, has already drafted a Clean Air Plan that incorporates the Early Action Compact.

Elected officials in the Clean Air Coalition of Central Texas are scheduled to consider a first-draft document that could lead to development of an Early Action Compact on Wednesday, October 9. The meeting is scheduled noon to 1pm in the board room of the Capital Area Planning Council, 2512 S. I-35, Suite 220. The Clean Air Coalition can’t delay the decision for long, however. An Early Action Compact must be completed and signed by local officials, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and EPA by December 31.

The protocol for the Early Action Compact has already been approved by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the EPA, but Kate Williams says the Early Action Compact was a direct result of the advocacy of the Alamo Area Council of Governments in San Antonio and the Clean Air Coalition leaders in Central Texas led by then-Mayor Kirk Watson. That advocacy led to the O3 Flex Agreement to address the one-hour ozone standard and it laid the groundwork for the Early Action Compact. Williams says the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality worked with the EPA and Environmental Defense in drafting the protocol.

An Early Action Compact must meet rigid milestones: By December 31, 2002, the compact, detailing the milestones for how the area will create its Early Action Plan, must be finished and signed. In 2003, technical work must be completed and control measures developed. In 2004, the Early Action Plan must be completed and integrated into the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality’s State Implementation Plan for submission to the EPA. In 2005, all control strategies must be implemented. In 2006, the local area reviews progress, makes reports, and updates the plan as needed. In 2007, the area must reach attainment of the eight-hour ozone standard. In 2008, the EPA designates the area as being in attainment, with no further requirements.

In a sense the Early Action Compact provides political cover for elected officials who would like to improve air quality but face possible opposition from a populace that is not necessarily aware of what’s at stake for public health and the economy. “It will take serious, hard-core measures to clean up the air in the Austin area, and it’s hard for elected officials to make those decisions if they don’t have support from the state and federal levels,” Kate Williams says. “That’s what the Early Action Compact does-provide support.”

Mayor Garcia, who is a board member of the Clean Air Coalition, says the need to educate the public has already been recognized, but beyond the efforts made by the Clean Air Force and the work done to recruit Clean Air Partners, not much has been done to reach the larger population. “We need to have a campaign that really gets the message to the people,” he says. “People don’t believe we have air-quality problems.” Garcia says that consultant EnviroMedia Inc. had proposed a public campaign comparable to the venerable “Don’t Mess With Texas” program, but when it became necessary to fund the campaign, “nobody came to the table.”

“We need that campaign,” the mayor says. “There are still too many (Chevrolet) Suburbans. There are still too many (Ford) Excursions. There are still too many people driving all the way from Luling, Bastrop, Dripping Springs, and Lakeway in their SUVs and their one-and-a-half ton trucks. These people don’t believe there are any air-quality problems.” (Garcia, by the way, is doing his share to lower emissions; he recently bought a Toyota Prius, a hybrid vehicle that gets about twice the mileage of similar sized cars and produces eighty percent fewer emissions.)

Williamson County Commissioner Mike Heiligenstein chairs the Clean Air Coalition. Does he support the idea of entering an Early Action Compact? “Absolutely—I think it’s worth a shot,” he says. “Whether it solves the problems or not, I don’t know. There has to be quantifiable goals and we have to meet them…We hope to get the support of industry.” Heiligenstein says he thinks that the other elected officials in the Clean Air Coalition will choose to support the Early Action Compact, just as they supported the O3 Flex Agreement.

What control measures?

Deciding what specific actions will be included in an Early Action Plan to reduce ozone pollution is something that will come later. All we know at this point is that the measures must not only reduce existing sources of ozone pollution drastically, but must do so despite growth in the population and industrial expansion.

Fortunately, we have a national expert in our midst to help determine what steps will be appropriate. Dr. David T. Allen is Reese Professor of Chemical Engineering and director of the University of Texas Center for Energy and Environmental Resources. He served as vice chair of the Committee on Vehicle Emission Inspection and Maintenance Programs for the National Research Council.

Allen has been studying Austin’s air quality for about five years. Some basic principals of his research are rooted in the concept that we have many of the same events happen most every day, such as industrial emissions and vehicular traffic, and weather is the main variable. The research involves studying representative historical episodes and developing a photochemical model to see if the model could have predicted what was observed in the historical episode. Once workable models are developed, they could be used to project into the future what emission control measures would be most effective in reducing ozone pollution. One type of model would be used, for example, to describe vehicle emissions and what emission reductions you might expect to achieve with specific actions, such as implementing a vehicle Inspection and Maintenance (I&M) Program or changing the speed limits.

A Texas I&M Program was legislated in the mid-nineties and was actually implemented under Governor Ann Richards’ administration. By January 1995, fifty-five testing stations were in operation to test vehicle emissions in Dallas-Tarrant County, Houston-Galveston, and Beaumont areas, but the Republican sweep of state offices in November 1994 brought cancellation of the program under newly elected Texas Governor George W. Bush. The Texas Legislature repealed the program in 1995, a decision that eventually resulted in a $200 million judgment against the State of Texas, in favor of contractors Tejas Testing I and II, says attorney Steve Bickerstaff, who led the team of Austin lawyers that represented the plaintiffs. Now in 2002, Texas is implementing a plan for mandatory emissions testing and repair of motor vehicles in certain parts of the state, a move that Bickerstaff calls “too little, too late.” Nevertheless, an I&M program may well be part of the Central Texas solution for reducing ozone levels, says Commissioner Heiligenstein. The Texas Vehicle Emissions Testing Program, also known as AirCheck Texas (“So we can breathe it. Not see it.”) currently applies to vehicle owners in Dallas, Tarrant, Harris, El Paso, Collin and Denton counties.

One consequence of an I&M Program is that its whole purpose is to find those vehicles that are polluting too much and either get them fixed or retire them. That might mean that low-income people, driving old cars they can’t afford to get fixed, would be hit hardest. Fortunately, the state has a program to assist low-income vehicle owners with repair, retrofit, and accelerated vehicle retirement.

It would seem that people might not be too crazy about the idea of being forced to get their vehicle emissions tested annually, pay an extra fee to do so, and be required to make vehicle repairs if necessary to limit emissions to acceptable levels. But a survey conducted by NuStats Market Research for the Clean Air Force of Central Texas indicated that the idea of tailpipe testing might be acceptable. The survey, conducted July 10-17, 2001, involved 199 residents selected at random from Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays, Travis and Williamson counties. Even when informed that a mandatory inspection program would cost them money, seventy-three percent of respondents reported being very likely or somewhat likely to support the fee. “It seems the majority of the population is willing to take responsibility for the maintenance of their vehicles in order to reduce ozone concentrations and improve air quality,” the report states. This sentiment seemed to hold true across the entire income spectrum.

But when it comes to speed limits, fuhgedaboudit. The NuStats survey didn’t even ask about the acceptability of lowering speed limits. When Houston was forced to cut the speed limit to fifty-five mph, people were outraged.

For now, the possible control measures needed to clean our air are being modeled, and it will be many months before elected officials are ready to propose specific actions. Further, the Protocol for Early Action Compacts requires broad-based local public input. Which is a good thing, because as a practical matter, it will do elected officials no good to promise control measures in the Early Action Plan that the public will not support. So don’t expect to see them floating the idea of reducing the speed limit.

The need to win public backing for the Early Action Plan is going to require an extraordinary amount of regional cooperation, first from the public officials who must sign the Early Action Compact, and then from the general public, upon whom achieving the necessary emission reductions depends. This will place unprecedented demands upon all citizens.

In a sense, the demands are analogous to the City of Austin’s recycling programs; the city can pick up recyclable glass, aluminum and paper products only if residents will sort their trash and put recyclables on the curb. This is indeed a minor imposition on ordinary citizens when compared to actions such as: keeping their vehicles tuned up; not driving to work or school alone; considering at least some of the time—and especially on Ozone Action Days—participating in carpooling or vanpooling, walking, or riding a bus or bicycle; participating in compressed work weeks and telecommuting to cut the number of days spent driving back and forth to work; getting out of the car and going inside to fetch hamburgers instead of idling in the drive-through lane; not filling the gas tank until after 6pm; and not using gasoline-powered lawnmowers, weed eaters, and leaf blowers until after 6pm.

In the end, the onus is on the individual who, once made aware of how each of us is dirtying the air, will see the wisdom of being part of the solution and not just part of the problem.

This story has focused upon the air quality in Central Texas and specifically on ozone. Ultimately, reducing emissions concerns matters of even greater importance, including global warming and dependence on foreign oil that has at times caused major disruptions to the American economy. Yet our gluttony for oil grows ever more insatiable.

Today, light trucks—which were allowed to meet a lower fuel economy standard when Congress established Corporate Average Fuel Economy standards in 1975—accounted for nearly fifty percent of the new vehicle market as of September 2001. In a report titled Increasing America’s Fuel Economy (see accompanying article, below, “Air Quality Resources”) “In 2001, the average fuel economy of new vehicles sold was at its lowest point since 1980. The proliferation of SUVs takes advantage of a loophole that allows what are essentially passenger cars to comply with the lower light truck standards, driving up the use of oil.”

What price must be paid to get that precious fuel into our gas tanks? Under the first President Bush, oil was the root cause of the Gulf War. Now another President Bush is rattling the saber and threatening another war against his father’s nemesis. Another war in the Middle East will not only destabilize the region politically but threatens to disrupt oil supplies or oil send prices skittering to who knows where.

As Rob Nixon wrote in an op-ed piece for the New York Times October 29, 2001, “For seventy years, oil has been responsible for more of America’s entanglements and anxieties than any other industry…The most decisive war we can wage on behalf of national security and America’s global image is the war against our own oil gluttony.”

Save fuel, save the country, and save our air. It’s up to each of us.

Three-year-old Jesse Saucedo has made several trips to the emergency room in his young life. He was a premature baby, and he still experiences breathing difficulties, with episodes of a “terrible cough” that come on every two or three months. Jesse’s mother, Carol Saucedo, says, “I told the doctor that on days when he’s having trouble breathing, I’ve noticed these are also bad air-quality days.” As a result, Saucedo says, “When this happens, I have him play inside instead of outside.”

Jesse has not been hospitalized for the ailment, and since his parents obtained a nebulizer to administer medications when his asthma flares up, he hasn’t had to go back to the emergency room.

Jesse Saucedo is just one example of a growing incidence of asthma. In fact, asthma is so prevalent that it’s even showing up in major Hollywood motion pictures: In Signs, the latest supernatural thriller from director M. Night Shyamalan (The Sixth Sense and Unbreakable), the character played by Mel Gibson has a son whose asthma affliction plays a key role in the plot.

But asthma and other breathing difficulties are anything but fictional. From 1994 to 1998, the last five years for which local statistics are available, eighty-one people died of asthma within the five-county area centered on Austin, according to the Texas Department of Health. Forty-eight of those deaths occurred in Travis County. Statewide, the rate of deaths from asthma has increased appreciably from 1980 through 1998, and more than 4,800 people were felled by the disease.

A study released last year by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that decreased citywide use of automobiles in Atlanta during the 1996 Summer Olympics led to improved air quality and a large decrease in childhood emergency room visits and hospitalizations for asthma. “Our study is important because it provides evidence that decreasing automobile use can reduce the burden of asthma in our cities and that citywide efforts to reduce rush-hour traffic through the use of public transportation and altered work schedules is possible in America,” said Michael Friedman, MD, epidemiologist in CDC’s environmental health program and lead author of the study published in the February 21, 2001, edition of Journal of the American Medical Association.

While many factors other than poor air quality can trigger an asthma attack, children, along with elders and others with breathing problems, are particularly susceptible to a witches brew of air pollution that results in high levels of ground-level ozone.

Bennie McWilliams, MD, is director of Pulmonary Pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Austin. He sees many children who, like Jesse Saucedo, suffer with breathing difficulties, some of which are exacerbated by high levels of ozone. Pound for pound, young children breathe more air than adults, and their lungs are in the early stages of development, McWilliams says. “The highest susceptibility is when kids are old enough to go outside and play outside,” he says. “Children should be limited in outside activities on Ozone Action Days.”

McWilliams sees such a strong correlation between air quality and children’s health that he serves on the board of the Clean Air Force of Central Texas, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving air quality.

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), roughly one of every three people in the United States is at a higher risk of experiencing ozone-related health effects.

Active children are at risk because they often spend a large part of the summer playing outdoors.

People of all ages who are active outdoors are at risk because during physical activity, ozone penetrates deeper into the parts of the lungs more vulnerable to injury.

People with respiratory diseases such as asthma may experience effects earlier, and at lower ozone levels, than less sensitive individuals.

Ozone can irritate the respiratory system and cause coughing, throat irritation, and uncomfortable sensations in the chest. Ozone can reduce lung function and make it more difficult to breathe deeply and vigorously. Breathing may become more rapid and shallow than normal. This reduction in lung function may limit a person’s ability to engage in vigorous outdoor activities.

Ozone can aggravate asthma. When ozone levels are high, more people with asthma have attacks that require a doctor’s attention or the use of additional medication. One reason this happens is that ozone makes people more sensitive to allergens, the most common triggers of asthma attacks.

Ozone can increase susceptibility to respiratory infections. Ozone can inflame and damage the linings of the lungs. Within a few days, the damaged cells are shed and replaced, much like the skin peels after a sunburn. Animal studies suggest that if this type of inflammation happens repeatedly over a long time period (months, years, a lifetime), lung tissue may become permanently scarred, resulting in less lung elasticity, permanent loss of lung function, and a lower quality of life.

To help protect human health, nine Texas communities, including Austin, are participating in the Ozone Forecast Program conducted by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (formerly Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission). The forecasted peak ozone concentrations are published on-line each day at Today’s Ozone Forecasts. The forecast is updated by roughly three o’clock each afternoon.

The forecasted ozone levels are classified within an Air Quality Index (AQI) that may be used as a guide to protect human health. The AQI is depicted on a scale from zero to 500; the lower the number, the better for health. The AQI is also published daily in the Austin American-Statesman.

The AQI ratings and attendant health concerns are as follows:

Zero to 50—The air quality forecast is good and there are no precautions for health.

51 to 100—The air quality forecast is moderate. Unusually sensitive people should consider limiting prolonged outdoor exertion.

101 to 150—The air quality forecast is unhealthy for sensitive groups. Active children and adults and people with respiratory disease such as asthma should limit prolonged outdoor exertion.

151 to 200—The air quality forecast is unhealthy. Active children and adults and people with respiratory disease such as asthma should avoid prolonged outdoor exertion.

201-300—The air quality forecast is very unhealthy. Active children and adults and people with respiratory disease such as asthma should avoid all outdoor exertion; everyone else, especially children, should limit outdoor exertion.

301 to 500—The air quality forecast is hazardous and everyone should avoid all outdoor exertion.

There is “good ozone” and “bad ozone.”

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the good kind occurs naturally in the earth’s upper atmosphere, ten to thirty miles above the earth’s surface, where it forms a shield that protects us from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays. This beneficial ozone, however, is being destroyed by manmade chemicals. An area where atmospheric ozone has been significantly depleted, for example over the North Pole or South Pole, is called a “hole in the ozone.”

The bad ozone is formed in the earth’s lower atmosphere when pollutants react chemically in the presence of sunlight. Ozone at ground level is a harmful pollutant, and is of concern during summer months, when the weather conditions needed to form it occur.

Ground-level ozone is one of six contaminants the EPA has designated as a “criteria air pollutant.” (The others are carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, particulate matter, and lead.) The EPA limits such pollutants by setting a “primary standard,” based on scientific information about what is needed to protect the public health. The standard is formally known as the National Ambient Air Quality Standard.

A geographic area in which the air quality does not exceed the primary standards is called an “attainment area.” An area that does not meet the primary standards is called a “nonattainment area.” The EPA is responsible to designate nonattainment areas when any of the criteria air pollutants exceed the permitted levels.

Unlike other criteria air pollutants, ozone is not emitted directly into the air by specific sources. Ground-level ozone is created by sunlight acting on nitrogen oxide (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are known as “precursor emissions.” There are thousands of sources of NOx and VOCs. Common sources of NOx include automobiles, trucks, construction equipment, power plants, industrial processes and household products such as hair sprays, paints, and foam plastic items. VOCs include many organic chemicals that vaporize easily, such as those found in gasoline and solvents. VOCs are emitted from many sources, including gasoline stations, motor vehicles, airplanes, trains, boats, petroleum storage tanks and oil refineries. In addition, biogenic (natural) emissions from trees and plants are a major source of VOCs. NOx and VOC emissions can be carried by winds for hundreds of miles from their origins and result in high ozone concentrations over very large regions.

The concentration of ozone in the air is determined not only by the amounts of ozone precursor chemicals, but also by weather and climate factors. Intense sunlight, warm temperatures, stagnant high-pressure weather systems, and low wind speeds cause ozone to accumulate in harmful amounts.

The EPA revised the primary standard for ground-level ozone in 1997. Until then, the “one-hour standard” was that ozone concentrations of 0.125 PPB (parts per billion) or above exceeded the standard. The standard is not to be exceeded in an area more than three times in three consecutive years at the same monitoring site. If the standard is exceeded four times in three years at one monitoring site, then the area is in violation of the standard and no longer in “attainment.” Four areas in Texas-Houston-Galveston-Brazoria, Beaumont-Port Arthur, Dallas-Fort Worth, and El Paso-are in nonattainment for the one-hour standard. The one-hour standard continues to apply to those communities which were not in attainment of that standard in July 1997.

The EPA announced an “eight-hour standard” in July 1997 and uses it to judge the air quality of all other communities. The standard is that the average of the annual fourth-highest daily maximum eight-hour average reading over a three-year period must be less than 85 PPB.

For the Central Texas air-quality region (which includes Travis, Williamson, Hays, Bastrop and Caldwell counties), ozone concentrations are continually monitored at two sites: Murchison Junior High School, 3724 North Hills Drive, and the Audubon site at 12200 Lime Creek Road.

A third monitoring site that is listed on the TCEQ web site for the Austin area is located in Fayette County. Since that site is not within the five-county metro area, however, its readings are not counted against the Austin area for the purposes of compliance. To date, the fourth-highest ozone reading at the Fayette site has not exceeded 80 PPB.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (formerly the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission) publishes on its web site the details aboutNational Ambient Air Quality Standards.

The Four Highest Eight-Hour Ozone Concentrations for the years 1997 through 2009 for all Texas air-quality regionsare also available on the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality web site.

There is a mountain of information and numerous organizations available for anyone interested in learning more about how to clean up air pollution. What follows is a sample of resources reviewed in preparation of the accompanying story, “Waiting to Inhale,” along with a brief description of each:

Organizations

Capital Metro—The only provider of public transportation serving the Greater Austin area is actively pursuing emissions reduction measures while maintaining its commitment to reliable service that gets people where they need to go. Capital Metro also provides a matching service to help people find vanpools and carpools to reduce the need to drive. Apply for these services on-line at www.capmetro.austin.tx.us/fbridepro.html or call 477-RIDE. For bus routes and schedules, call Capital Metro’s Go Line at 512-474-1200.

City of Austin Air Quality Program—Information is available on-line at www.ci.austin.tx.us/airquality. (This link is no longer functional.)

Clean Air Coalition of Central Texas—This is a coalition of county judges and mayors of cities from Bastrop, Caldwell, Hays, Travis and Williamson counties that are setting policy for air quality measures in this region. For more information, call the Clean Air Force at 512-916-6047.

Clean Air Force of Central Texas—This is a nonprofit organization working to reduce air pollution in Central Texas. For details, visit www.cleanairforce.org or call 512-916-6047.

Clean Air Partners—The program’s purpose is to enlist the help of businesses and their employees in the effort to keep our city livable, healthy, and prosperous. For details, visit www.cleanairpartnerstx.org or call Transportation Management Group, program coordinator, at 512-350-6581.

Center for Air Quality Studies—A division of the Texas Transportation Institute, Texas A&M University. Its mission is to help Texas and national agencies find ways to improve air quality to meet federal standards. See http://tti.tamu.edu/inside/centers/cfaqs or call Brian Bocher, director, at 979-458-3516.

Drive Clean Across Texas—This program is touted as the nation’s first statewide public outreach and education campaign designed to improve air quality. The goal is to boost awareness and change attitudes about air pollution, and to ultimately inspire changes in driving behavior that will help clean up the air in Texas. The campaign is jointly sponsored by the Texas Department of Transportation, Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and Federal Highway Administration. For details, visit www.drivecleanacrosstexas.org.

Galveston-Houston Association for Smog Prevention—This is a community-based environmental organization dedicated to improving the quality of the region’s hazardous air through public education, participation in the state and federal planning process, and active advocacy in appropriate venues. For details, visit www.ghasp.org or call 713-528-3779.

Safe Routes Texas—This is a construction program administered by the Texas Department of Transportation. Its goal is to provide school children with a safe route to walk or bike to school, thus reducing motor vehicle trips. For details, visit www.saferoutestx.org.

Sustainable Energy and Economic Development Coalition—This Austin-based nonprofit organization advocates for clean air and clean energy. For details visit www.seedcoalition.org or call 512-637-9481 or 512-797-8481.

Texas Bicycle Coalition—This Austin-based nonprofit advocacy organization works to advance bicycle access, safety and education. For details, visit www.biketexas.org or call 512-476-RIDE.

Reports

2009 Annual Urban Mobility Report, published by the Texas Transportation Institute, Texas A&M University. The report identifies trends and examine issues related to urban congestion, and is available on-line at http://mobility.tamu.edu. [Note: Date of report updated 10-14-09.]

City of Austin Ozone Strategies, a guide to the strategies and initiatives undertaken by the city to vastly reduce its emissions of ozone precursor emissions. The information in this report provides a wealth of ideas that could be adopted by private businesses and other organizations.

Clean Air Plan for the San Antonio Metropolitan Statistical Area. This draft is designed to enable a local approach to ozone attainment and to encourage early emission reductions that will help keep the area in attainment of both the one-hour and eight-hour ozone standard, and so protect human health. The plan is available on-line at www.aacog.dst.tx.us/cap/CAP2002.html#1. The report provides a model with which to compare the similar plan being drafted by the Clean Air Coalition of Central Texas for the Austin region.

Do Something: City of Austin Air Quality Program, provides a variety of information about how we can help make air cleaner, available on-line at www.ci.austin.tx.us/airquality.

Impact of Changes in Transportation and Commuting Behaviors During the 1996 Summer Olympic Games in Atlanta on Air Quality and Childhood Asthma. An ecological study prepared by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, which shows that limiting commuter trips improves air quality and reduces emergency room visits and hospitalizations for children with asthma. Available on-line at jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/285/7/897.

Increasing America’s Fuel Economy: The Fastest, Cheapest, Cleanest Way to Reduce Oil Dependence, published in February 2002 by the Alliance to Save Energy, American Council for Energy-Efficient Economy, Natural Resources Defense Council, US Public Interest Research Group, Sierra Club, and Union of Concerned Scientists. The report is no longer available on-line but other information about increasing fuel economy can be found online at ase.org/content/article/detail/6062.

Latest Findings on National Air Quality: Air Trends, published by the US Environmental Protection Agency, is available at www.epa.gov/airtrends/index.html.

New Source Review, the official version of recommendations prepared for President Bush by the US Environmental Protection Agency concerning the impact of the regulations on investment in new utility and refinery generation capacity, energy efficiency, and environmental protection. For another viewpoint, read State of the Air: 2002 (see below).

O3 Flex Agreement, a voluntary local approach to encourage emission reductions that will keep Central Texas in attainment of the one-hour ozone standard, while also working toward the health benefits envisioned in the eight-hour ozone standard.

Protocol for Early Action Compacts Designed to Achieve and Maintain the 8-Hour Ozone Standard, published by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (formerly Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission). The protocol is available on-line at www.tceq.state.tx.us/implementation/air/sip/eac.html.

State of the Air: 2009, published by the American Lung Association, a group that insists that all of the provisions of the nation’s Clean Air Act be enforced. The report is available at www.stateoftheair.org.

Surviving and Thriving Without Driving: A Field Guide to Goods and Services in Downtown Austin, published by the City of Austin to promote the use of public transit and human-powered transportation in downtown Austin. [Note: As of 10-14-09 this report was no longer accessible online.]

The Plain English Guide to the Clean Air Act, published by the US Environmental Protection Agency, is available on-line at www.epa.gov/air/caa/peg.

The Plain English Guide to Tailpipe Standards, published by the Union of Concerned Scientists. The report is available on-line at www.ucsusa.org/clean_vehicles/vehicle_impacts/cars_pickups_and_suvs/the-plain-english-guide-to.html.

Vehicle Emissions Testing in Texas, also known as AirCheck Texas (“So we can breathe it. Not see it.”) currently applies to Dallas, Tarrant, Harris, El Paso, Collin and Denton counties. Information about the program is available on-line at www.tceq.state.tx.us/implementation/air/mobilesource/vim/overview.html. This is a resource for comparing any future vehicle emissions testing program that may be advocated for use in Central Texas.

—Ken Martin

In the Austin area, the ozone season for 2002 runs from April 1 through October 31. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) designates an Ozone Action Day for the Austin area for each day in which ozone concentrations are forecasted to reach 85 PPB (parts per billion) averaged over an eight-hour period. Ozone Action Days are announced by all major media outlets to alert the public to take voluntary actions to help reduce the formation of ground-level ozone.

The TCEQ provided the following ten tips that citizens can use to help prevent ground-level ozone: Share a ride to work or school. Avoid morning rush-hour traffic. Walk or ride a bicycle. To avoid the need for extra travel, take your lunch. Combine errands to reduce trips. Avoid drive-through lanes, where automobiles must idle for extended periods. Postpone refueling until after 6pm. Don’t top off your gas tank when refueling. Postpone using gasoline engines such as lawnmowers until after 6pm. Keep your vehicle properly tuned to reduce emissions.

One way to avoid driving is to ride the bus. Capital Metro makes it easy by making the ride free on Ozone Action Days. Capital Metro also offers a vanpool program and will facilitate finding people to carpool with through its matchmaking service. You can apply for these services on-line at www.capmetro.austin.tx.us/fbridepro.html. Or call 477-RIDE to get matching information about carpools and vanpools. For bus routes and schedules, call Capital Metro’s Go Line, 474-1200.

We can also help by reporting vehicles that appear to be spewing out extraordinary amounts of smoke from their tailpipes. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality provides a “Smoking Vehicle Program” through which anyone caught in traffic behind a car, truck or bus that is emitting smoke can take action. If that smoke is billowing out for more than ten consecutive seconds, write down the license number, date, time, and location you saw the smoking vehicle. Within thirty days, call 1-800-453-SMOG or go on-line and make the report at www.tceq.state.tx.us/implementation/air/mobilesource/vetech/smokingvehicles.html. You do not have to identify yourself and the report is free. The state agency will get word to the vehicle owner. Although fixing the car is voluntary, thousands of vehicle owners have replied saying they have done so. Experts on tailpipe emissions say that about ten percent of the vehicles on the road account for about fifty percent of the emissions, so waking up these heavy polluters is definitely worth the effort.

How employers can help

Employers can play a big part of solving area air pollution problems. They can: Shift work schedules to allow employees to avoid morning rush-hour traffic. Allow employees to work at home through telecommuting. Offer bus passes. For employees who rideshare or use public transportation, provide a guaranteed emergency ride home. (Capital Metro offers a guaranteed ride program only to vanpool, express, and flyer service riders operating exclusively within the Capital Metro service area.) Carpool to lunch and meetings. Schedule meetings that don’t require driving, either by meeting on site or by making conference calls. Offer free drinks to encourage employees to eat at work. Postpone fueling company vehicles until after 6pm. Postpone working with mowers, bulldozers, backhoes, tractors and any two-cycle engine activities. Delay painting, degreasing, tank cleaning, ground maintenance and road repair. Postpone routine flaring or venting of hydrocarbons. Postpone the loading and hauling of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Postpone VOC-producing activities such as chemical treatment and catalyst preparation. Switch loads to fired heaters or boilers with low nitrogen oxide burners.

These suggestions are only the beginning of what can be done to make Austin’s air quality a whole lot better. For more ideas, explore the reports and contact the organizations listed in the accompanying article, “Air Quality Resources.”

Phillip Martin, deputy director at

Phillip Martin, deputy director at  The District 6 candidates started the opening remarks. Matt Stillwell, whose

The District 6 candidates started the opening remarks. Matt Stillwell, whose  Jimmy Flannigan said the relationships he has built through working with the Austin Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce made him stand out among the other candidates.

Jimmy Flannigan said the relationships he has built through working with the Austin Gay and Lesbian Chamber of Commerce made him stand out among the other candidates.