He served more than four years 1997-2001

Kirk Watson, the highest-profile Democrat running to be Austin’s next mayor, has long ago been there, done that, and yet he wants another crack at leading city government. Which raises the question: what kind of a mayor was he before? And what does that portend for the city if he defeats the other five people running for the job?

The three leading candidates, Watson, State Representative Celia Israel, also a Democrat, and Republican Jennifer Virden, through October 11th had raised $1.8 million, spent more than $800,000. As the Bulldog reported, between them they had $1.2 million in cash on hand to grab voters’ attention and plead for votes. And, we can be certain that even more money will have poured into their campaign coffers when the final pre-election reports due October 31st are filed. Who’s going to be scared when those Halloween Day reports pour in?

The candidates are spending an awful lot of money for a job that will last two years and pays $134,191 annually, plus allowances of $5,400 for a car and $900 for a cell phone.

But this election is not about personal gain. It’s about power, who gets to wield it, and what they would do with it. Like all council members, the mayor has just one vote, but the mayor has the bully pulpit and drives the agenda. In city politics, the public perception is the buck stops at the mayor’s desk.

How are we to pick the best person to lead the city until 2025? We can listen to what the candidates have to say while stumping and in the endless round of debates. But for Watson, maybe the best indication of what he’s capable of doing as mayor is to examine what he accomplished as Austin’s mayor from June 15, 1997—when he was first sworn in—till his last City Council meeting November 9, 2001. That’s four and a half years.

Where will this information come from and who am I to measure the past performance of the man who would be mayor…again?

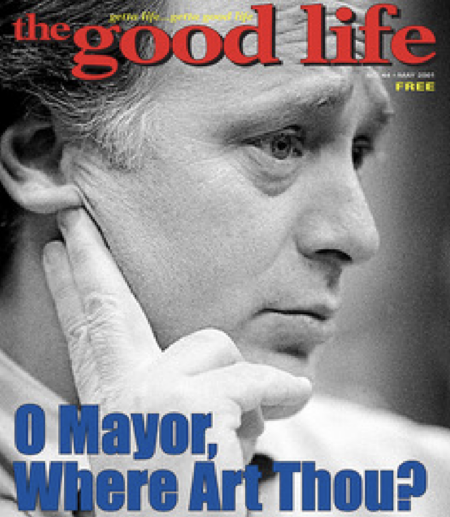

Briefly, as a journalist I covered every City Council meeting and City Council work session during the first three-plus years of Watson’s tenure for my In Fact weekly newsletter. In July 1999, I took the newsletter daily five days a week. After I sold the newsletter in July 2000, it changed hands a couple more times and was later rebranded as the Austin Monitor, but I continued to cover local government and politics for another decade with our monthly, magazine, The Good Life.

Watson immediately took the lead

A quarter-century ago, just 10 days into Watson’s first term, the eager-beaver 39-year-old new mayor initiated a two-day retreat for the council and senior city staff. It was held June 25-26, 1997, at a remote LCRA facility in Bastrop. I witnessed firsthand the at times withering criticism of city staff and their responses. Late in the retreat during face-to-face confrontation, after listening to more than an hour to mostly criticism of city staff’s performance, City Manager Jesus Garza joked, “I want to retire to my room and cry,” then added, “For the things mentioned today, we accept responsibility.”

For the first three years of Watson’s stint as mayor I was on the beat for every hour of City Council meetings. Then, as now, meetings often stretched far into the night. I was on the job at 12:35am March 13, 1998, when other reporters had long since departed and the council voted to call a bond election for $210 million.

On May 2, 1998, voters approved those $210 million in bonds, which included $65 million to buy environmentally sensitive land over the aquifer. Setting aside money to preserve open space was a first-ever achievement that would never have happened under previous city councils whose majority had opposed the Save Our Springs Ordinance. At an outdoor celebration on election night I witnessed the wild dancing and great satisfaction of a crowd that included not only environmentalists like Save Our Springs Alliance leader Bill Bunch, but Mayor Watson, City Council Member Daryl Slusher, City Manager Garza and Assistant City Manager Toby Futrell. All were dragged into the center space to dance to music made by just drums and a cow bell. Nothing could have more forcefully demonstrated the success of team-building between council and staff that began with that June 1997 retreat.

Today, that initial effort to protect the aquifer, combined with later voter approval of several more bonds, has resulted in the purchase of more than 28,000 acres of Water Quality Protection Land in the Barton Springs contributing and recharge zones.

What else happened on Watson’s watch? Not everything that went down during his years at the helm can be described as a win for Watson. A lot of what happened was initiated by previous City Councils and followed through under Watson’s leadership. And some things initiated by others were opposed by the mayor. This summary includes a mixture.

Campaign finance reformed

Less than six months after Watson took office, as a result of a petition drive led by Austinites for a Little Less Corruption, in a November 4, 1997 election voters overwhelmingly approved a City Charter amendment to clamp down on the influence of money in mayor and council elections. The proposition limited candidate contributions to $100 per donor. Had that restriction existed during Watson’s first campaign he would never have pulled in the $749,000 that he raised.

The delay in getting this reform on the ballot was the city clerk had ruled the petition insufficient. Petitioners cried foul and filed a federal lawsuit. Judge Sam Sparks issued a stinging decision that called the clerk’s process for reviewing petitions “draconian.” He rebuked the city for trying to defend it. That election, which could’ve been held for free in connection with the May 1997 council elections, instead would up costing the city $337,000 for a special election and attorneys fees for both sides.

Its effect on future mayor and council elections was profound. Although the limit has since been raised to $450 for the 2022 elections, candidates must now gather support from a far larger base of individual donors.

Redevelop municipal airport site

Years before Watson took office voters approved $400 million in airport system revenue bonds to build a new airport at the former Bergstrom Air Force Base. Ballot language included a provision that Robert Mueller Municipal Airport would close once the new airport was opened. In October 1997 the city hired Roma Design Group of San Francisco to guide the project.

After fending off efforts by the state and Texas Legislature to buy land at Mueller or keep it open as an airport, redevelopment proceeded. By the time Watson left office in late 2001 the City Council had winnowed the list of candidates for a master developer for the project to three finalists. Today the 711-acre site offers a model for close-in urban redevelopment that provides high-density housing, offices and entertainment.

Ready Austin’s electric utility for competition

Mayor Bruce Todd’s proposal to sell the city-owned utility didn’t attract support from a council majority and in 1995 work was started to cut costs and prepare for competition. The Bulldog’s coverage of that era was summarized in our previous report.

On Watson’s watch the city kept the utility, continued to cut costs, and ultimately never entered retail competition. The utility continues to provide big dividends that help to reduce property taxes., The city’s budget for 2022-2023 shows that Austin Energy contributed a $115 million in transfers into a general fund that totals $1.3 billion. Of that total, $785 million is allocated to public safety for police, fire, and emergency medical services.

Although the LCRA and the city are partners in the Fayette Power Project, which the LCRA operates, in many other matters they were frenemies, working to achieve their separate goals and interfering in each other’s business.

Revise land code

In recent years, after losing appeals in court, the city is in a holding pattern for revising the Land Development Code. That despite having paid consultant Opticos Design Inc. $7.8 million between 2013 and 2019. The goal to revise the code stretches to at least as far back as Watson’s first term in office. In March 1998 Watson kicked off a meeting of the 21-member Smart Growth Initiative Focus Group that would meet every other week. He said the goal was to within seven months implement a faster, cheaper and simpler land development process. He said the economy could be sustained only if the environment is protected, and cited decisions by Dell Computer Corp. and Motorola Inc. to locate in the Desired Development Zone as evidence that growth can be encouraged with incentives in the form of infrastructure improvements. “We can’t have overreliance on consensus-making at the expense of decision-making,” Watson said.

Start the flood control tunnel

A year after Watson was elected, on May 2, 1998 voters approved $25 million for the construction of a 5,600-foot-long tunnel, buried 70 feet below the surface. When finished it would protect one million square feet of expensive downtown real estate, stretching from 12th Street south to Lady Bird Lake. Taking that land out of the flood plain would allow its development and boost property taxes revenue for all taxing jurisdictions.

After voters approved the money the LCRA offered to manage the project. The City Council authorized negotiations despite environmentalists’ efforts to, as part of the deal, get the LCRA to tighten rules on new development where the agency going to build a waterline to Dripping Springs. The LCRA offered a turnkey project to finance, design and build the tunnel, and would throw in $1 million of in-kind services for the project. But the love boat sunk when the council put too many conditions on the deal and in November 1998 the LCRA quit the project.

Construction didn’t begin until April 2011. Whether or not the LCRA foresaw back then that constructing the Waller Creek Tunnel would cost far more than the $25 million approved by voters, in hindsight they were saved from being associated with a project that ended up costing $162 million—six and a half times the originally projected cost—paid for with tax increment financing. When finally completed the project also enhanced the decade-long redevelopment of the 11-acre Waterloo Park and planning for the 1-1/2 mile Waterloo Greenway that would follow the creek’s path.

Love thy neighbor cities

Just about the time Watson took office, a consensus-building group started working on ideas for providing the cities of Rollingwood and West Lake Hills access to the City of Austin’s sewer service. The idea was to help those cities, whose residents suffered from failing septic systems, but to do so without compromising Austin’s environmental objectives.

In February 1998 the council authorized negotiations. Service for Rollingwood was okayed in August 1998. West Lake Hills finally got approval in May 1999 but service was restricted to the most troubled areas, to prevent future extension to environmentally sensitive territory beyond the city.

Cut the water deal of a century

In October 1999, just 16 minutes after the council had voted unanimously to approve an agreement to reserve a raw water supply for 50 years and an option for another 50 years, LCRA General Manager Mark Rose signed the agreement and literally pocketed two checks that totaled $100 million. That was just a down payment on a deal the city estimated would cost $1.3 billion over a half-century.

The deal was negotiated in secret for 10 months and paid for without the voter approval required by the City Charter. This deal didn’t surface till early June 1999 via an article in the Austin American-Statesman but it had been brewing in secret since summer a year before. That’s when the City Attorney Andy Martin hired a law firm to negotiate in secret with the LCRA for an amount not to exceed $39,000. The law firm was running up a big bill but to avoid public awareness, the item never got on the council agenda for approval of a higher amount. Once the deal finally surfaced, Mayor Watson wanted to push it through quickly. But Bill Bunch of the Save Our Springs Alliance rallied broad support to slow down the deal. A series of public meetings were held to answer the public’s questions.

Council Member Bill Spelman said, “What we’re buying is not just water; we’re buying control over our destiny.”

As part of the deal the LCRA agreed not to use any part of that $100 million to extend its waterline into western Travis and northern Hays counties. A federal lawsuit filed by environmental groups trying to stop construction of that project was unsuccessful. The LCRA constructed a line that initially supplied water to Dripping Springs. Later expansion would take the water north on Ranch Road 12, then back down Hamilton Pool Road to Highway 71 to complete a loop. That waterline opened up land for development in the recharge zone for the Barton Springs segment of the Edwards Aquifer where the city had hoped to minimize development to protect the sole source of drinking water for tens of thousands.

Build a digital downtown

When Watson took office the city owned several downtown blocks that had sat idle for decades. Efforts to revitalize downtown started by going all out to get Computer Sciences Corp. to build its new headquarters on the city’s land, bringing its 1,300 current employees and plans for another 2,200 jobs. In April 1999 the council voted unanimously to approve a 99-year lease of three blocks for a one-time payment of $11.9 million. CSC was to build three six-story office buildings, but ultimately built two. (Eventually the city bought back one of those blocks.)

In March 2000 the council awarded an architectural contract to build a new city hall on the site of the old city hall annex. In December 2000 the council notched another win by approving $25 million in fee waivers and grants for software company Vignette to build its new offices on Cesar Chavez. Ultimately the dot.com bubble burst and Vignette’s downtown construction was not completed. But downtown developments would include not only a new city hall flanked by Computer Sciences Corp’s new buildings but also AMLI high-rise apartments.

Initiate civilian oversight of police

In early 1999 the Sunshine Project for Police Accountability launched a petition drive aimed at opening police personnel files. By late May that year the City Council voted 6-1 to approve Council Member Bill Spelman’s initiative to form a Police Oversight Focus Group. That group, composed of representatives of police, activists and the Greater Austin Crime Commission, met almost weekly for nine months. I covered every meeting.

Members made a trip to the Bay Area of California, where several cities had some form of police oversight. They attended a national conference. They got presentations from the police department and heard citizens complain that they feared for their lives and civil liberties. The meetings were often contentious and emotions could run high.

By late March 2000 the group haggled its way to consensus to recommend establishment of a Police Monitor who would birddog investigations of police misconduct and a Police Review Panel consisting of nine people appointed by the council to hear complaints. Panelists would receive police training, ride with police officers, and meet with those interested in police oversight. Police disciplinary records would continue to be shielded from public view unless conduct resulted in a suspension.

Ultimately implementation of police oversight would depend on the city’s meet and confer negotiations with the Austin Police Association for a new contract. In February 2001 it was announced that the Austin Police Monitor’s office would be established at a cost of $619,000 The city manager would hire the monitor and an assistant.

Scott Henson, a member of the Police Oversight Focus Group that spent nine months studying various systems of oversight before making recommendations, was disappointed. He said the group’s recommendations had been “gutted like a fish” during the meet and confer process. “They took every significant piece we thought gave real accountability and neutered it down to nothing.” Meanwhile the new police contract called for giving police pay raises totaling $32 million over the coming three years.

Flash forward to recent years and the City of Austin has paid tens of millions of dollars to people injured by police in demonstrations in the wake of George Floyd’s death, most by “less lethal” ammunition used in crowd control. The district attorney indicted 19 police officers accused of using excessive force during those 2020 protests. Activists today continue to call for increased civilian oversight of the Austin Police Department. The Austin Monitor reported August 10th that Equity Austin had submitted 33,000 petition signatures in support of the Austin Police Oversight Act. If approved by voters, the Act would remove police oversight from the meet and confer negotiations for a new police contract, which are currently underway. The city council voted to put the matter before voters in May 2023.

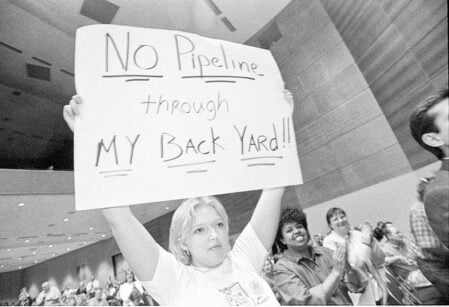

Oppose reactivation of the Longhorn Pipeline

One thing the city and LCRA definitely agreed on was the danger to area water supplies posed by a 450-mile-long pipeline built in the 1950s to transport West Texas crude oil to Gulf Coast refineries. It was acquired in 1995 by Longhorn Partners with the aim of lengthening the pipeline and reversing the flow to carry gasoline and other refined products from Houston area refineries to markets in West Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

Nearly 9,000 people lived within 1,250 feet of a 20-mile segment of pipeline that crossed South Austin. In Austin, a Halloween 1999 protest warned of the danger: instead of being ripped to shreds by Freddie Krueger you’d be blown to bits by an exploding gasoline pipeline. If you survived you’d have to deal with a water supply polluted beyond repair. Opposition was so fierce the EPA had to shut down a public meeting on the pipeline. More than 500 people crammed the seats at Bowie High School and hundreds more waited outside. Mayor Watson got a huge ovation when he took the stage to bring calm. He pointed out the safety hazard posed by the overcrowded facility and announced the EPA would extend the comment period.

In January 2000 the hearing was resumed in Palmer Auditorium and even more people turned out. In the end, as part of an environmental agreement, Longhorn Partners replaced 19 miles of the 50-year-old pipeline over a segment of the Edwards Aquifer with thicker-walled pipe. Yet on August 13, 2013, after the flow had been reversed to once again transport oil to refineries, the pipeline leaked about 300 gallons of crude in southwest Austin.

Watson destined to try bigger challenges

“Yells and a prolonged standing ovation greeted Mayor Kirk Watson yesterday in City Council chambers,” In Fact Daily reported December 9, 1999. “To the surprise of absolutely no one, Watson told a standing-room-only crowd that he will seek a second term.”

Among the accomplishments of his first term Watson counted $100 million to preserve parks and water quality protection lands; a formerly stagnant downtown transformed into a 24-hour digital downtown; and major incentives to induce Dell Computer Corp., Motorola Inc., and Computer Sciences Corp. to build within the Desired Development Zone. He said the police department was up to full strength for the first time in decades and had achieved the lowest crime rate in 18 years. “We have secured water that will be the envy of Texas and the nation.”

“Now is the time to make our lives and the lives of our children the best they can be in Austin, Texas,” he said. “Let’s go back to work,” he concluded, to another standing ovation with hoots and yells and sustained applause, as he moved into the crowd to bestow handshakes, hugs and kisses.

Five months after making his reelection announcement, and with opponents consisting of two homeless people and a cab driver, on May 6, 2000, Watson secured a second term with 84 percent of the votes. That set an all-time record for the highest percentage of votes won by an Austin mayor running for reelection. Turnout was an anemic 7 percent.

Watson’s second term short-lived

Watson’s last council meeting wasn’t until November 2001, when he was succeeded by Gus Garcia, who easily won a special election. The sendoff included a performance by the O. Henry Middle School Orchestra that included Watson’s son Preston, ending with “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow,” joined by the audience.

City Manager Jesus Garza said, “Your leadership enabled us to complete in four and a half years what we have tried to do for decades.”

Rumors and press coverage of Watson’s impending departure started even before his reelection year ended. I wrote a feature story about it in our magazine, The Good Life, published in May 2001—six months before he fled to seek higher office. I noted our original interview of August 1996 in which he conceded the mayor’s job is not usually a stepping stone to higher office. In my “Letter from the editor” column that same month, seeing the writing on the political wall, I bid an early farewell and thanked him for his service.

By the end of his tour as mayor, a high-tech downturn had taken some of the snap out of the springboard for higher office. But Watson was heavily courted by a Texas Democratic Party desperate for candidates who might win a state office, an achievement denied the party since 1994.

Ultimately Watson jumped the good ship Austin and joined the so-called Dream Team slate to run for the state’s highest offices: El Paso banker Tony Sanchez for governor, former state comptroller John Sharp for lieutenant governor, and Watson for attorney general. In 2002, Sanchez easily defeated his primary opponents while Sharp and Watson went unopposed. But the dream of Democratic resurgence was shattered in the general election. Rick Perry beat five opponents and finished 18 points ahead of Sanchez, David Dewhurst eased by Sharp with a 6-point margin, and Greg Abbott whomped Watson by 16 points.

It would be four more years before Watson found a new political goal. He was elected to represent State Senate District 14 in 2006. He was never opposed in a Democratic Primary and easily won reelection in 2010, 2014, and 2018. He resigned the senate office in April 2020 to be the founding dean of the University of Houston’s Hobby School of Public Affairs. His dance with academia soon ended and he launched a bid to be Austin’s mayor once again.

If he wins, Watson will be a quarter-century older and far more politically experienced than he was the first time he took center stage as Austin’s mayor. He’s not the first former mayor trying to recapture their youth. The question for voters will be do they prefer a blast from the past or a fresh face?

Trust indicators: I launched the In Fact newsletter covering city hall and local politics in July 1995. In August 1996 I got a two-hour interview with mayoral candidate Kirk Watson. For the next nine months I covered his campaign, along with three city council races, right through the May 3, 1997 election. In addition, I covered every city council meeting and work session from July 1995 through July 2000, as well as all mayoral and council elections in those five years. After selling the In Fact newsletter where I published most of my work about Watson, I wrote about him for The Good Life magazine that we published, including articles about his mayoral resignation.

Trust indicators: I launched the In Fact newsletter covering city hall and local politics in July 1995. In August 1996 I got a two-hour interview with mayoral candidate Kirk Watson. For the next nine months I covered his campaign, along with three city council races, right through the May 3, 1997 election. In addition, I covered every city council meeting and work session from July 1995 through July 2000, as well as all mayoral and council elections in those five years. After selling the In Fact newsletter where I published most of my work about Watson, I wrote about him for The Good Life magazine that we published, including articles about his mayoral resignation.

Related documents:

In Fact newsletter July 2, 1997 (3 pages)

O Mayor, Where Art Thou?, The Good Life, May 2001 (5 pages)

Letter from the editor, The Good Life, May 2001 (1 page)

Related Bulldog coverage:

Candidates offer competing visions on homelessness, October 18, 2022

2022 candidates have raised $3 million-plus, October 14, 2022

The man who would be mayor…again, October 10, 2022

Want to get elected but not be accountable? September 28, 2022

Mayor and council candidates rake up $2.3 million, September 7, 2022

Urbanists vie to replace council member Kathie Tovo, August 30, 2022

Let the mayor and council campaigns begin, August 22, 2022

Dear Ken, Thanks for the memories of the 2 day “Council Retreat”! You may not remember, but I attended the retreat. I think I was the only one there that was just a “citizen”…. It was at that retreat that I met Toby Futrell… I had not known her before. After the retreat, several of us would have coffee with Toby at a place on Congress Ave near the old City Hall… I had known Beverly Griffith for a number of years, and now she was on Council – and Sally Shipman had moved to Houston. Toby allowed the city’s “surveyor” to examine the boundaries of the Sand Beach Reseerve land that Roberta Crenshaw, Susan Frost and I had tried to return to the city after a “developer” had include portions of it in his project … And the land was returned to the City BUT NOT in the place it should have gone! Mayor Watson let the developer have use of most of the land, with the rest of the land going to the very back of the tract, next to the railroad tracks… The land that went back to the city on the Town Lake side of the tract unfortunately became “Road” to the re-development of the old Power Plant – and thus didn’t become parkland… Thanks Mayor Watson…

I really enjoyed working with Toby Futrell and was sorry to see her leave the city….And I really enjoyed the Council Retreat!!! Sincerely, Mary Arnold

Mary thanks for your interest and taking time to write and share your recollections. Actually I didn’t recall that you were at the retreat. You weren’t quoted in my In Fact coverage of it and I just forgot. That said, I just uploaded and linked the In Fact newsletter of July 2, 1997, which provides three pages of my report about the retreat.

Any Democrat running for office cannot be trusted to have the best interest of either our Nation or the Austin taxpayer at heart. They have proven this time and time again with their sanctuary city and open border agendas. Democrats frown on public safety as a whole and purposefully and unapologetically single out police departments as racists and as bad people. The Austin Mayor and this nine member Council are guilty of this and have no respect for the jobs that our law enforcement people have to do.

Safety and security of our Nation and the Austin taxpayers are not a Democrats concern. Their main concern and their happy place is beating their social drum for the for illegal immigrants, homeless, vagrants, drug addicts, gangs, felons, thieves, prisoners, societal dropouts and the like. They would much prefer that the taxpayer have no input on running our government or how they spend our money, and to just shut up and pay their taxes and put up with the slight inconveniences of homeless camps in our green belts, crap and urine on our sidewalks and parks, personal assaults, stabbings, robberies, murders, B&E’s, car thefts, rapes, shootouts etc.

All under the Democrats governance in cities Nationwide and here in Austin!

I agree with Fedup so we should instead vote for Save Austin Now’s endorsed candidates most of whom have only been in Austin for a few years bringing their extremist ideas to make Austin the homeless capital of the world with regulated homeless campsites and focusing on the green algae, solar panels, and flood the city with investment real estate and short term rentals that they can capitalize off of. If they decide to submit their financial statements, we can see how well they manage their own money with all their own student and other loans and credit card debts and so now they should also be allowed to manage the taxpayer dollars!

In response to Fedup: Please note there are 10 council members rather than nine.

Thanks for the extremely informative article Ken. You weave these threads into a whole piece very well. Like me, I imagine most readers, remembered some of this, had forgotten much of it, and never knew a lot more. This was a valuable retrospective.

Thanks for taking the time to write, John. I’m glad the article was useful.

It was only because I had copies of all the issues of In Fact and In Fact Daily I published that I was able to reconstruct all of this information. If memory alone were required I would have been in trouble.

During his first stint as mayor, Kirk Watson and the Austin Transportation Department developed a 25-year plan to relieve Austin’s traffic congestion. It worked for a few months and then created even worse congestion. Mr. Watson focuses on short term solutions instead of doing the hard work of finding the sources of problems and eliminating them.