About 5,200 words

About 5,200 words

The May 13, 2006, election offers Austin voters at least eleven reasons to do what citizens have been doing less and less of in recent decades: actually vote. If ever there was a time to cast a ballot, it’s now.

Voters will determine not only who will be our mayor and council members in Places Two, Five and Six, but also will decide the fate of seven amendments to the Austin City Charter. The charter is the city’s de facto constitution and it will be in full force and effect in perpetuity unless amended. Because of the charter’s permanence, in the long run these proposed amendments may mean far more to Austin’s future than who fills which chairs on the council dais for the next three years.

Of the seven propositions on the ballot to amend the charter, Propositions One and Two are easily the most complex and controversial. (Propositions Three through Seven are outlined in an accompanying article, below.)

Proposition One (Open Government Online) and Proposition Two (Save Our Springs) reached the ballot through a petition drive started last November. Petitioning was led by the Save Our Springs Alliance (SOSA), the ACLU’s Central Texas Chapter, and the Austin Regional Group of the Sierra Club. More than twenty thousand registered voters signed petitions to put these propositions on the ballot.

These two amendments are lengthy. This is a summary:

Proposition One—The Open Government amendment would protect privacy while opening access to city business, city functions, and top city officials’ calendars and communications.

Further, the amendment would provide access to information related to civil litigation and settlements, economic development, and agency memoranda—all of which have been withheld in the past.

It would also require that meet-and-confer contract negotiations between the city and a police officers’ association be open to the public. Past meet-and-confer meetings have been closed. This resulted in “gutting” civilian oversight and granting overly generous police raises at the expense of social services, proponents say.

This measure would open to public scrutiny Austin Police Department personnel files that have been kept closed but which are readily available in many other law enforcement agencies, including the Travis County Sheriff’s Office.

This measure would open to public scrutiny Austin Police Department personnel files that have been kept closed but which are readily available in many other law enforcement agencies, including the Travis County Sheriff’s Office.

ACLU proponents of police accountability say the weak civilian oversight and closed personnel files have helped fuel and perpetuate community distrust of police, especially in view of Austin’s history of minorities dying at the hands of police officers.

The requirement to make all public information available online would be phased in over time, “as expeditiously as possible and to the greatest extent practical,” judgments that ultimately would be up to the City Council.

Who wouldn’t want open government and why? The opponents to Proposition One base their opposition on two main points: high estimated cost, which could cause postponement of the planned November bond election, and loss of privacy.

Central to the question of both cost and privacy is that opponents argue Proposition One would require city e-mails to be put online in real time, a task the city estimates would cost thirty-six million dollars the first year and twelve million dollars annually, forcing an increase in property taxes. Proponents say the city’s interpretation is mistaken, that e-mails would not go online but instead must be archived for future retrieval in response to a public information request.

Proponents say Proposition One will save money by opening closed-door government deals to public scrutiny, that it’s the government’s privacy opponents want to protect, not citizens’ privacy which is already protected by law.

Proposition Two—The Save Our Springs charter amendment aims to reinforce the current Save Our Springs Ordinance by strengthening city policy to direct development to areas outside the Barton Springs-Edwards Aquifer watershed.

It would eliminate subsidies for development within the Barton Springs watershed, including but not limited to tax abatements, infrastructure commitments, fee waivers, and consent to create utility or other special districts.

The proposition also would require greater scrutiny of “grandfather” claims that allow projects to be constructed in the Barton Springs watershed under old water-quality regulations. The City Council would have to approve grandfathering by a two-thirds majority vote in open session. Since enactment of the SOS Ordinance in 1992, grandfathering decisions have been made by a committee meeting in closed session. Opponents say this could invite intervention by the Texas Legislature, while proponents contend nothing is being changed except to allow the public to witness and comment on how grandfathering decisions are made.

Austin’s three major environmental organizations want Proposition Two to be approved, while developers and most on the city council don’t.

During the council meeting of March 9, Austin City Council members voiced strong opposition to Propositions One and Two before unanimously approving language to describe these measures on the ballot. (Read the transcript at www.ci.austin.tx.us/council/2006/council_03092006.htm.)

On March 28 a lawsuit challenging the ballot language was filed in state district court by plaintiffs Jeff Jack, Glen Maxey, Ann del Llano, Paul Robbins, Jordan Hatcher and Peggy Horowitz. District Judge Stephen Yelenosky on March 31 ruled that the city had “exceeded its discretion by adopting ballot language that does not fairly portray the chief features of the…charter amendments.”

Yelenosky’s ruling stated the ballot language was both negative and incomplete. The ruling also said that the costs of implementing Proposition One as described in the ballot language—thirty six million dollars initially and twelve millions a year thereafter, and requiring a tax increase of three cents per hundred dollars of valuation or a reduction in city services—was “not sufficiently certain and references a tax increase that the city concedes is not compelled by the proposed measure.”

The judge ordered the city to revise the ballot language. The City Council met April 3 and adopted language that addressed only the specific shortcomings cited in Yelenosky’s ruling. Because time had run out to get the ballots printed, proponents said it was too late to file another lawsuit. Thus the council’s wording is what voters will see on the ballot.

“We believe the ballot language is still not a ‘fair portrayal’ of either amendment,” SOSA Executive Director Bill Bunch stated in an e-mail. “In both instances, the ballot language is still clearly hostile and argumentative—basically electioneering.”

Bunch says the language omits any mention of Proposition Two’s true purpose and is intended to frighten residents by indicating they won’t get services they need. He says the language also makes it sound like the proposition would take away someone’s property rights—maybe yours. “We cannot take away any property rights even if we wanted to,” he stated.

Bunch says the language omits any mention of Proposition Two’s true purpose and is intended to frighten residents by indicating they won’t get services they need. He says the language also makes it sound like the proposition would take away someone’s property rights—maybe yours. “We cannot take away any property rights even if we wanted to,” he stated.

As for prohibiting the city from participating in “certain road projects,” as the ballot language states, Bunch says restrictions only apply to toll roads that would be financed based on projected trips to serve major sprawl in the watershed. This is crucial, because the City Council and the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization have already approved one and a quarter billion dollars to pave the Barton Springs watershed with highways and toll roads—“spending money to do what nobody wanted,” Bunch said. For a fraction of that, he said, more land in the watershed could be purchased for preservation and the roads wouldn’t be needed. That would “free up one billion dollars for transportation to put development where we want it.”

Kathy Mitchell is the local ACLU chapter president and campaign treasurer for the Clean Water Clean Government Political Action Committee (PAC). She says the ballot language in Proposition One still errs in stating that it requires “private e-mails to public officials be placed on the city web site in ‘real time,’ including e-mails or electronic communications between private citizens and public officials in all city departments, and limit the ability of citizens to keep private the details of these communications, unless legal exceptions apply.”

Putting e-mails online is not required, Mitchell says. The amendment only requires the city to establish a system that automatically archives e-mails involving council members, the city manager and assistant city managers, their staff members, and city department heads. These e-mails are already recognized as public records under the Texas Public Information Act. The purpose of the amendment, Mitchell says, is to ensure that e-mails are maintained for public disclosure when requested. To ensure they are, officials would be prohibited from using private e-mail accounts for city business. Privacy would be fully protected under existing laws, she said.

Mayor Pro Tem Danny Thomas cast the only vote against the revised ballot language. Thomas says, “I think we should have compromised a little bit more with the people who bought the petitions. That’s what the judge was trying to tell us…I couldn’t support what was passed and put on the ballot…I agree with the amendments they brought forth. We should have done more to make it more clear (on the ballot).”

The mayor pro tem said while he wants voters to approve both propositions, the proponents have been put at an unfair disadvantage. “Will it pass?” Thomas said. “I don’t think so because of the language.”

The proponents of these measures faced off with opponents in a two-hour debate April 13 at St. Edward’s University.

Arguing for were Bill Bunch and Ann del Llano, a lawyer who has worked with the ACLU for sixteen years, mostly as a volunteer.

Arguing against were former Mayor Gus Garcia, who left office in 2003, and former City Council Member Daryl Slusher, who left office in June 2005. Since September 2005 Slusher has been employed by Austin Energy, which like all city departments would be subject to these amendments.

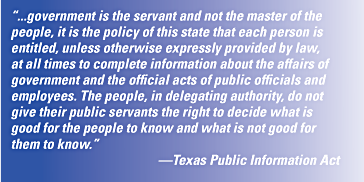

In describing the overarching purpose of enacting Proposition One, Del Llano began by quoting some of the opening words of the Texas Public Information Act: “…government is the servant and not the master of the people, it is the policy of this state that each person is entitled, unless otherwise expressly provided by law, at all times to complete information about the affairs of government and the official acts of public officials and employees. The people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not good for them to know.”

Del Llano said the thrust of Proposition One is for information that is already available to the public by law be made accessible online as soon as “practical, possible, and with privacy protected.”

She said the city’s estimated cost of thirty-six million dollars the first year and twelve million dollars a year thereafter for achieving this result is “false.”

“We all know the Internet saves money,” del Llano said. “Insider deals cost money.” She provided a pungent example of why the Open Government Online amendment was needed: “We didn’t know about it when the city negotiated four hundred million dollars in a police contract and left social services out in the cold.”

Del Llano displayed a chart that showed a total of more than two hundred and thirty-nine million dollars had been awarded to nine projects by the City Council. These included one hundred million dollars for a water deal with the Lower Colorado River Authority; fifty-eight million dollars for Samsung; thirty-seven million for Simon Property Group; and fifteen million dollars for Stratus Properties.

Slusher said this isn’t money the city spent in all cases, but income, some of which is abated to the developer. It should be noted, however, that the LCRA sum was indeed money the city spent—one hundred million dollars in cash, up front. The other deals were done in the name of economic development, but were “done deals” before the public learned about them, critics say.

Bill Bunch outlined the high points of Proposition Two. He said it would require development applications and staff comments about them be placed online, and a public comment section be created to give citizens equal standing.

In the current system of development, Bunch said, citizens “are always late to the party. We’re not invited.” As a result, he said, “We get a city built for developers.”

As an example of how projects are kept from public view, he noted the previous day’s front-page article in the Austin American-Statesman about the city water treatment plant proposed in Roy Guerrero Colorado River Park. (This idea so enraged East Austin residents and park advocates that the City Council was soon forced to wave a white flag and consider other sites.)

Contrast that to how planning could work under Proposition One, proponents said. Citizens would been informed the park was being considered, and public input would have created a better plan from the beginning.

Daryl Slusher presented the opposition to Proposition One. Slusher criticized the way in which Propositions One and Two were brought about. He said eight to ten people drafted the propositions, signatures were collected and the petitions were “sprung on the city” and “now we get to decide.” Slusher did not mention that this is how citizen initiatives have typically always gotten on the ballot, as provided for in the Austin City Charter. (To put it in perspective, the Declaration of Independence was written by one man, Thomas Jefferson. As for who did write these propositions, see accompanying article, below, “Who Drafted Propositions One and Two.”)

Slusher said Open Government Online could cause a tax increase and lost productivity as council members and top managers are required to log their conversations involving city business. Despite assurances by proponents that e-mails would not be required to be placed online, Slusher claimed the proposition would require it.

“It’s not the words said here that matter,” Slusher said, “but what is written on the page.”

Responding to a question from the moderator about costs, Bunch said, “The city is already committed to putting the (land) development process online, but they didn’t intend to give the public the password.” He said the cost of public access being added was small, and savings would accrue when citizens got a heads-up on “insider deals.”

Del Llano repeated that the city was already working to put its land development process online, “but they crossed out the two hundred thousand dollar cost of letting the public see it.”

Garcia nevertheless maintained, “It’s unfair to pass this when we don’t know what it will cost.”

What is the cost? Bunch said, “It’s too much of a ‘black box’ to put a fixed number on, but I believe (it will cost) a few million at most to do the mandatory parts” of Proposition One.

Del Llano added that while no one is certain of the cost, the city’s witnesses had conceded under oath in the lawsuit trial that no tax increase was mandated.

Garcia said he saw no need for Proposition One. “We don’t have a crisis of information,” he said. “If anything there’s too much information flowing. All of our meetings are open where we make decisions. Why is this on the ballot if there’s no crisis? And if there is a crisis, why put this in the charter?”

When answering questions from opponents, Bunch said, “It cracks me up to hear how sacred the (city) charter is. I imagine no one here has read it. What’s sacred here is the soul of our city—not this charter. If something is in here (in the amendment) that’s not exactly right…that’s such a trifle compared to losing the soul of our city.”

Del Llano said, “This belongs in the charter because it’s about the transparency of our government and the transparency of our water.”

In the Save Our Springs debate, Slusher led off by saying the amendment would have no effect on AMD’s plans to build its new facility over the aquifer. He said the amendment might prevent the city from being able to negotiate future agreements that would result in less impervious cover on grandfathered tracts.

“This will be a lose-lose proposition for the environmental community,” Slusher said. “I’m glad they’re not united.” (While some individual environmentalists oppose the propositions, this seems a curious claim, given that Austin’s three major environmental groups—SOSA, the Sierra Club and the Save Barton Creek Association—were involved in drafting the petitions and have endorsed both propositions.)

In presenting the proponents’ case for Proposition Two, del Llano said the people of Austin had spoken in 1992 by overwhelmingly approving the SOS Ordinance.

“It did work,” she said of the ordinance. “Companies were afraid to go there.” But that has changed, she said. “Today, AMD is going there. It’s time to stand up again now or we will lose our treasure.”

Bunch said although application of the SOS Ordinance has been restricted somewhat by state legislation, for many years the community respected the mandate. Today the mandate is being ignored “because they think we’ve forgotten.” He noted that the City Council had refused even to pass a nonbinding resolution to discourage AMD for building on the aquifer.

He said the grandfathered rights being used by AMD were not legitimate because the original project was to have been a shopping center, not a major employment center. “The law is clear. When the project is not the same, the decision rests at the local level,” he said, and “the council cowed.”

Bunch conceded the charter amendment would not legally bar AMD’s project, but said if it passed he hoped AMD would respect the community’s wishes. Bunch challenged the opponents to join him in a press conference to ask AMD to “please stand down and honor our community.”

Slusher replied, “I’ll say it here. I ask Hector Ruiz (AMD’s CEO) not to locate over the aquifer.”

Slusher agreed with Bunch that AMD building on the selected site “would set off other development and cause pollution. I think they should locate in the Desired Development Zone.”

At the end a half-dozen audience members were allowed to ask questions, touching off further exchanges among the panelists.

Slusher criticized Propositions One and Two for not containing definitions of what was meant by certain terms. “These two amendments are based on distrust of the City Council, yet you let the city define what these mean,” he said.

Bunch acknowledged the amendments did not define terms because that would be inappropriate. “Imagine if the U.S. Constitution had a definition for ‘freedom of speech’ or ‘due process of law,’” he said. (In point of fact, the existing Austin City Charter contains no section defining terms.)

In response to an audience question about whether the Open Government Online amendment might result in cost savings, Bunch said, “That’s a critical point,” as it makes instantly available information that otherwise must be manually produced upon request. He said implementing this amendment would be similar to what was achieved when the state implemented the Texas Legislature Online system (www.capitol.state.tx.us).

Slusher agreed the Texas Legislature Online system was good, adding, “The city does the same thing with the council agenda and back-up material…but you cannot find out who Texas legislators talked to today…People will stop talking to council members because it will get on the Internet.”

Another audience member criticized the extended secret negotiations between the city and the LCRA for a long-term water agreement. Slusher said the negotiations were secret at first but “the city needed to do this. It provides water for the city for fifty years and the option for fifty more years.”

Bunch countered, “The point is it should not have been a secret deal” that over the long term will cost the city a billion dollars. “The city’s water policy says planning should have been an open process that involves everyone…The council is trying to run our city and spend a billion dollars, and we get to watch a City Council meeting and scream for three minutes,” he said to loud applause, referring to the amount of time citizens are allowed to address the council.

The campaigns have already begun to wage a war of ideas to win the hearts and minds of voters. Both the Austin American-Statesman and The Austin Chronicle have editorialized against these propositions.

On April 16, Kathy Mitchell, the treasurer of the Clean Water Clean Government PAC, said the proponents had thirty-eight thousand dollars in the bank. “We will try to communicate with voters through all available means,” she said.

Mitchell anticipates voters will favor passage of these amendments to the Austin City Charter, just as they did in passing the Save Our Springs Ordinance in August 1992 by the overwhelming margin of sixty-two percent in favor.

She said that a poll conducted in mid-February indicated, “People love open government and they really want to see things change in Austin. We believe when they understand what these amendments do, they will vote for them overwhelmingly.”

Bunch is also upbeat about the chance for these propositions to pass.

“We’re going to do our best to run a campaign and debunk all those lies and have faith in Austin voters that open government is resisted by the powers that be for a reason, and they’re very much afraid of it,” Bunch said.

“There is a high level of trust in organizations like the ACLU and various environmental groups that are supporting these amendments,” Bunch said. “I’m hoping that at least more than half of the voters will see through all that disinformation and go with the basic idea that Internet-based systems (will be an effective way) to hold our community more accountable and more transparent, and that the time is here to take back our local government from corporate special interests.”

The corporate interests that Bunch decries are sparing no effort to defeat these measures. Of the three PACs voicing opposition, the only one that had raised significant sums through early April was the Committee for Austin’s Future. This PAC netted more than a hundred and eighteen thousand dollars. All of it came in large contributions from major business interests.

Greg Hartman, treasurer of the Committee for Austin’s Future, is a veteran of many campaigns. When asked to describe the result of his PAC’s polling, Hartman used language remarkably similar to Kathy Mitchell’s. He said, “When you have an amendment that goes by the title of open government and water quality, people think they must be a good thing. But once you describe what’s in the amendments, the voter rejection of these amendments is overwhelming.”

In Fact Daily on February 14 quoted Hartman saying, “Both amendments are…full of vague language that we believe could ultimately jeopardize the privacy of anyone who has dealings with the City of Austin including just asking a question. It will cost local taxpayers tens of millions of dollars, send the city to court indefinitely, and lead the Texas Legislature to weaken, not strengthen, our ability to protect local water quality.”

Although Hartman describes himself as a “progressive Democrat” and a supporter of the ACLU, he refuses to accept the ACLU’s assurances that privacy will be protected under Proposition One.

Hartman says the judge’s order to strike from the ballot language the city’s estimated cost of thirty-six million dollars to implement Proposition One, does not render the figure meaningless. “You can argue it’s going to be less or it’s going to be more but it’s still going to be significant expenditures,” he said.

Bunch said the city failed to address the possibility of saving money by doing business online. “They’re already moving to do development permitting online because it’s so efficient and time-saving. Just like in the private sector, the city is moving as fast as it can to put information online. You can do work, store it immediately for instant retrieval, and get customer to do a lot of work for you. It’s ‘through the looking glass’ to argue it will cost so much more than you’ll save.”

Nevertheless, the opponents don’t accept assurances about costs and privacy and they’re using these issues to drive home their message with voters.

The EDUCATE PAC (Environmentalists and Democrats United for Charter Amendment Truth and Education) mailed a political flier in mid-April to selected parts of the city hammering these points. The mailer is headlined “Costs Too Much, Goes Too Far,” a variation on the “No Rail: Costs Too Much, Does Too Little” slogan that opponents used to narrowly defeat Capital Metro’s light-rail campaign in November 2000.

The flier noted that the Capital Area Progressive Democrats, Central Austin Democrats, and West Austin Democrats were opposed to both propositions, and that the University Democrats were opposed to Proposition One.

Ted Siff, treasurer of EDUCATE PAC, says the cost of Proposition One would force the city to delay a bond election that had been planned for November. On that point he is echoing what Council Member Betty Dunkerley said in the council meeting of March 9. The contention is that if the city’s estimated cost were valid, the city couldn’t go into debt to pay for other needs because the money to repay the bonds would be chewed up by these propositions.

Siff says the city staff estimates that “seventy-five hundred acres of land over the aquifer is under imminent threat of development. If we postpone the bond election for an indefinite time, say a year, at least hundreds of those acres will be developed and lost.” The bond election would likely include somewhere between forty-five million and seventy-five million dollars to buy land for preservation, Siff said.

Proponents Bunch and Mitchell said there would be no need to delay the bond election. “It’s clear that (the estimated thirty-six million dollars) is putting literally every shred of information on line in the next few years—and that’s not required by the amendment and that’s not practical. When it’s passed they will abandon that concept immediately,” Bunch said.

The fact that proponents maintain the bond election would not be delayed does not reassure Siff, who has previously served with the Trust for Public Land and the Austin Parks Foundation.

“Forty-five million dollars for conservation rights or purchasing land is a heck of a lot better for eliminating pollution than pulling us into court for the next decade,” he said.

Bill Bunch said, “We wouldn’t endorse something Orwellian (a term used to label these propositions in a Statesman editorial). We endorse the reverse of that. Orwell says it’s horrible when government is looking at you. This says you’re looking at government. We do recognize that we’re up against the biggest interests in the city—because they don’t want to come out of the backrooms.”

Anyone trying to decide how to vote on these measures must ask: who drafted these measures and whose interests do they represent?

Kathy Mitchell—president of the ACLU’s Central Texas Chapter and treasurer of the Clean Water Clean Government Political Action Committee—identified the following individuals:

ACLU representatives Ann del Llano (a lawyer), Scott Henson, and Mitchell.

Save Our Springs Alliance lawyers Bill Bunch, Brad Rockwell and Sarah Baker.

Jordan Hatcher, a technology advocate and board member of EFF-Austin, a group that promotes the right of citizens to communicate and share information without unreasonable constraint.

Also consulted were:

Mary Arnold, a longtime environmental activist and former board member of the SOS Alliance.

Lucy Dalglish, executive director of The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.

Harold Daniel, president of the Save Barton Creek Association.

Rebecca Daugherty, director of the Freedom of Information Service Center, a project of The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.

Katherine Garner, executive director of The Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas.

Robert Jensen, associate professor in the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Journalism.

Donna Tiemann, a board member of both the Austin Sierra Club and Save Barton Creek Association.

Proposition Five—This would raise to three hundred dollars the limit on campaign contributions a candidate for mayor or council may accept from an individual contributor. The current limit is one hundred dollars, as approved by seventy-two percent of voters in November 1997. The new limit if approved would be adjusted annually based on the Consumer Price Index.

Further, candidates would be authorized to accept contributions totaling thirty thousand dollars per election, and twenty thousand dollars for a runoff, from sources other than natural persons eligible to vote in a zip code partially or wholly within the City of Austin. The current limit on such contributions is fifteen thousand dollars per election and ten thousand dollars in a runoff. The addition of the zip code would make it easier to verify compliance.

Proposition Seven—This amendment would allow the terms of municipal court judges to be four years instead of the current two years. Municipal court judges are appointed by the City Council.

These articles were originally published in The Good Life magazine in May 2006

Historical footnote: The detailed results of the May 13, 2006, election for these propositions is posted on the City of Austin’s Election History web page. A summary is provided as follows:

Proposition 1: Failed (yes 24%, no 76%).

Proposition 2: Failed (yes 31%, no 69%)

Proposition 3: Passed (yes 82%, no 18%)

Proposition 4: Passed (yes 55%, no 45%)

Proposition 5: Passed (yes, 68%, no 32%)

Proposition 6: Passed (yes 68%, no 32%)

Proposition 7: Passed (yes 64%, no 36%)